Kids of Kabul

Authors: Deborah Ellis

Tags: #Children—Afghanistan—Juvenile literature. Children and war—Afghanistan—Juvenile literature. Afghan War, #2001Children—Juvenile literature

KIDS OF KABUL

LIVING BRAVELY THROUGH

A NEVER-ENDING WAR

DEBORAH ELLIS

GROUNDWOOD BOOKS / HOUSE OF ANANSI PRESS

TORONTO BERKELEY

Text copyright ©2012 by Deborah Ellis

Published in Canada and the USA in 2012 by Groundwood Books

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Distribution of this electronic edition via the Internet or any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal. Please do not participate in electronic piracy of copyrighted material; purchase only authorized electronic editions. We appreciate your support of the author’s rights.

This edition published in 2012 by

Groundwood Books / House of Anansi Press Inc.

110 Spadina Avenue, Suite 801

Toronto, ON, M5V 2K4

Tel. 416-363-4343

Fax 416-363-1017

or c/o Publishers Group West

1700 Fourth Street, Berkeley, CA 94710

www.houseofanansi.com

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

Ellis, Deborah

Kids of Kabul : living bravely through a never-ending war / Deborah Ellis.

eISBN 978-1-55498-203-5

1. Children—Afghanistan—Juvenile literature. 2. Children and war—

Afghanistan—Juvenile literature. 3. Afghan War, 2001- —Children—Juvenile literature. I. Title.

HQ792.A3E55 2012 j305.235092’2581 C2011-906638-6

Front cover photo: Gilles Bassignac / Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

Back cover photo: Paula Bronstein / Getty Images

All other photos are courtesy of the author.

Design by Michael Solomon

We acknowledge for their financial support of our publishing program the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council, and the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF).

To the next generation of survivors

Introduction

I am a feminist, which means I believe that women are of equal value to men. I am from Canada, a country not without its struggles but where women and girls are not limited — in theory — by the fact that they are female. When I heard about the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan in 1996, and the crimes they perpetrated against women and girls, I decided to get involved.

This started me on a journey that has taken me from Afghan refugee communities in Canada to the muddy tent camps in Pakistan and the decrepit Soviet workers’ holiday hotels outside Moscow that, ten years ago, served as encampments for Afghan and other refugees. It is a journey that has spawned four books: an adult book (

Women of the Afghan War

) and three novels about children under the Taliban, the last one published in 2003.

And now I’ve gone back.

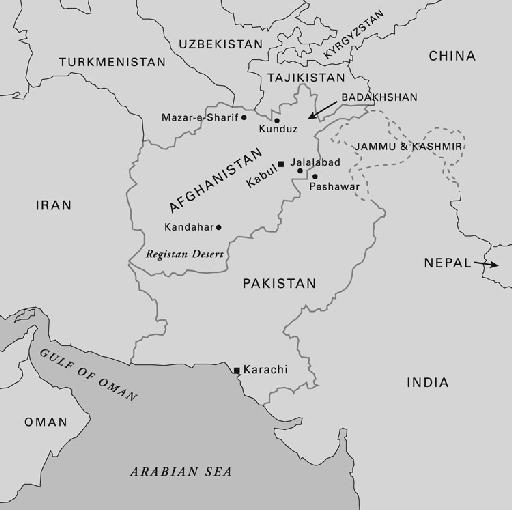

Afghanistan has been at war for decades. It has been used by the world’s great powers in their struggles against each other. One such struggle produced the Taliban government, which, at an earlier stage of the war, had been supported by the United States. Among other things, the Taliban regime was brutally repressive toward women. The Taliban also harbored al-Qaeda, the terrorists who were responsible for the September 11th attacks on the United States in 2001. The war that followed initially overthrew the Taliban government but has continued for the past eleven years.

The real losers are the Afghan people, especially the women and children. Their daily lives are still threatened by suicide bombings, armed conflict and other forms of violence, and even Kabul, the capital city, is not secure. Tens of thousands of Afghans have died since 9/11 — many, many more than died in the twin towers. People have been injured, maimed, displaced and terrorized. People are hungry, people are fleeing, and families are separated from their homes and from each other. Refugees who left their homes as long as twenty years ago live in informal camps where they have no services other than those offered by one or two NGOs. This means there are still millions of internally and externally displaced Afghans living in miserable conditions without water, plumbing or electricity. The billions and billions of dollars spent on the war, which might have been spent on education, health care, housing and rebuilding a civil society, have been spent on weapons.

So has anything been gained?

For some young people life has improved, and they are grabbing hold of every opportunity with both hands. Though more than half the children in Afghanistan still have no access to schooling, those who do study hard. When they are allowed to play sports, they play hard. The lucky ones who have money and who live in Kabul and a few other cities are reaching out to each other and to the world, using social media and new technologies. Some institutions are bringing them into contact with music and art. And they are finding ways to take their considerable energies and talents into public life to move their country forward.

The interviews in this book were conducted over the weeks I was in Kabul early in 2011. Many of the young people spoke only Afghan languages, so their words were translated into English for me by an interpreter — the same interpreter for many of the interviews.

Children’s playground in a park just north of Kabul.

Although I usually travel alone, this time I traveled with Janice Eisenhauer and Lauryn Oates from Canadian Women for Women in Afghanistan. Many of the places I visited were involved with projects funded by Women for Women. Due to the security situation, I did not travel beyond Kabul.

It is possible to read the interviews in this book and come away feeling hopeful about the future of these kids and the future of their country. It is good to be hopeful, and if the future could be in the hands of this generation of young people, with their eagerness, openness and determination, then Afghanistan could indeed be a garden again.

Sadly, the old way of doing things — the way of corruption and killing and suspicion and venal international interests — seems to be gaining the upper hand. But there is no question that we must reach out and support these young people and the Afghan organizations that work with them. Only through work at the grassroots level can the patient day-to-day of rebuilding take place.

We have to stand together to move forward. Anything we can do to connect with Afghan people, to appreciate what they have been through and what they are capable of, and to assist them in getting the education they need to rebuild their own country will be a step away from madness and pain, and a step toward the sunshine.

Deborah Ellis

2012

Faranoz, 14

During the Taliban regime, schools for girls were closed, and women were forbidden from attending university. Extreme poverty coupled with decades of war and chaos have left the country with high rates of illiteracy. According to the United Nations Human Development Report of 2008, only 28 percent of Afghan adults can read and write. That number drops to 13 percent for women.

Since the fall of the Taliban, the international community has partnered with the people of Afghanistan to raise literacy levels and encourage education for all. It is an uphill struggle — one undertaken at times with enthusiasm and at times with suspicion. In addition to regular schools, literacy classes have been introduced into non-traditional spaces to make them as accessible and acceptable as possible.