Insectopedia (45 page)

Still, the real headline grabbers were the celebrity serial killers. What did Ted Bundy, Ted “the Unabomber” Kaczynski, and David “Son of Sam” Berkowitz have in common? Gallegly had the answer: “They all tortured or killed animals before they started killing people.”

26

It made good copy, but I doubt even the politicians believed this link between crush videos and mass murder. After all, many of them had already listened to Susan “Minnie” Creede, the D.A.’s undercover investigator, as she testified before the Subcommittee on Crime about the psychology of the crush fetishist. After almost a year in the Crushcentral chat room, Creede was an expert witness.

“They spoke about their fetishes and how they developed,” she told the committee.

For many of them the fetish developed as a result of something they saw at a very early age, and it usually occurred before the age of five. Most of these men saw a woman step on something. She was usually someone who was significantly in their lives. They were excited by the experience and somehow attached their sexuality to it.

As these men grew older, the woman’s foot became a part of their sexuality. The power and dominance of the woman using her foot was significant to them. They began to fantasize about the thought of being the subject under the woman’s foot. They fantasized about the power of the woman, and how she would be able to crush the life out of them if she chose to do so. Many of these men love to be trampled by women. Some like to be trampled by a woman wearing shoes or high heels. Others like to be trampled by women who are barefoot. They prefer to be hurt and the more indifferent the woman is to their pain, the more exciting it is for them.

I have learned that the extreme fantasy for these men is to be trampled or crushed to death under the foot of a powerful woman. Because they would only be able to experience this one time, these men have found a way to transfer their fantasy and excitement. They have learned that if they watch a woman crush an animal or live creature to his death, they can fantasize that they are that animal experiencing death at the foot of this woman.

27

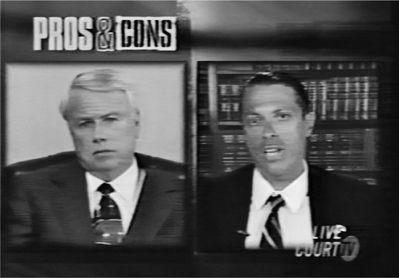

Congressman Gallegly also heard much the same thing from Jeff Vilencia during their encounter on Court TV. “The viewer identifies with the victim,” Jeff stated flatly in an attempt to counter Gallegly’s alarming claim that crush freaks were dangerous sadists. The fetish “starts in childhood, when the child observes an adult person, usually a woman, stepping on an insect,” he continued, echoing Creede, his legal nemesis. “He becomes sexually aroused, sort of by happenstance, and as he becomes an adolescent, he eroticizes his behavior in his sexuality, and it becomes a part of his love map—” (“His

love map

?” interrupted the host incredulously.)

Without an origin story, how else can Jeff refute Gallegly’s fantasies of the crush freak as the proto–serial killer and the insect as the proto-baby? There’s no space for refusal. At the center of a frighteningly

unstable public debate (TV host: “Jeff Vilencia, are you a tiny bit afraid you’re going to be prosecuted? You’re the one producing these films”), explanation is Jeff’s only option. He has to explain that his fetish has a specific history that ties it to specific objects, that it is masochistic, and that masochism—as the philospher Gilles Deleuze argues in his famous discussion of Sacher-Masoch—is not a complementary form of sadism but part of an entirely distinct formation. A “sadist could never tolerate a masochistic victim,” writes Deleuze, and “neither would the masochist tolerate a truly sadistic torturer.” The distinctions abound: the masochist demands a ritualized fantasy, he creates an anxiety-filled suspense, he exhibits his humiliation, he demands punishment to resolve his anxiety and heighten his forbidden pleasure, and—quite unlike the sadist and with Sacher-Masoch as the locus classicus—he needs a binding contract with his torturess, who, through the contract (which, in truth, is no more than the masochist’s word), becomes the embodiment of law.

28

But if only it really were that straightforward. When, in a reflective moment, Jeff tells me that the one thing he learned from all of this was that “women are really cruel, just really evil, man,” and he says it bleakly, with not a hint of teasing, I see that I haven’t quite got the hang of this, and I’m not sure that Deleuze has either. Isn’t the point that cruelty is

part of a compact, that there is agreement, tacit or explicit, about boundaries and needs? Isn’t that what all Jeff’s banter with Elizabeth and Michelle is probing? Admittedly, at the end of Sacher-Masoch’s

Venus in Furs

, Wanda lets loose her Greek lover on Severin with the full force of his hunting whips. It’s horrible, and unexpected too. But it’s also a momentous effort on her part to finally break his dependency, to enforce that break by unambiguously stepping outside the contract. Wanda strains for the gesture that will free them both without the death of either. Under this assault, writes Sacher-Masoch, Severin “curled up like a worm being crushed.” All the poetry is whipped out of him. When it is finally over, he is a changed man. “There is only one alternative,” he tells the narrator, “to be the hammer or the anvil.” Henceforth, he’ll be the one doing the whipping.

29

But could this be what happened to Jeff too? Only differently? Did the furies of Fox News strip him of his pleasures? Was that tense but playful self somehow swept away in the storm of disgust that poured down on him? The wrong kind of suffering. Game over, lights on. Cruelty is suddenly just cruelty, Michelle is just Michelle, stomping on animals and maybe actually enjoying it. No longer a goddess, no longer exciting. Just mean.

Such a long road to get here. A road paved with explanation. Explanation was straightforward for investigator Susan Creede. Her task before the House subcommittee was to manufacture an object that could be acted upon by the law. Think of her as the forensic expert narrating the corpse. But it’s so much more complicated for Jeff Vilencia. It’s not simply the demands of the moment that force him to speak Creede’s language. Among the DVDs, videos, books, audiotapes, unpublished writings, and press clippings he sent me when we first talked was an unexpected item: a three-page article he’d written called “Fetishes/ Paraphilia/Perversions.” The essay begins programmatically: “Perversions are unusual or important modifications of the expected pattern of sexual arousal. One form is fetishism, of which crush fetishism is an example.” It goes on to describe seven theories of fetish formation (“oxytocin theory,” “faulty sexualization theory,” “lack of available female contact theory,” and so on) and includes as an appendix a discussion of the seventeen “possible stages of fetish development basic to the modified

conditioning theory” which both Jeff and Susan Creede used to explain the birth of the crush freak to Congressman Gallegly.

At the time I didn’t understand why Jeff wanted me to have this essay. Nor did I understand why he had dedicated

Smush

to Richard von Krafft-Ebing, the pioneering nineteenth-century Viennese sexologist whose

Psychopathia sexualis

documented “aberrant” sexual practices as medical phenomena. But then I got to the second volume of

The American Journal of the Crush-Freaks

, published in 1996, which is subtitled: “Just where do we fit in, in all of this?” In the introduction, Jeff writes:

Imagine all of the shame you would feel having no one to talk to about your desires. It is as alone as one could feel. You might as well be stranded on an island someplace.

Well those dark days are behind us now. As we move towards the 21st century, and as various sexual groups have come out over the years, I cannot see any reason that people should feel shame any more….

There are more choices today than there ever were. When I was a kid, I was a crush-freak, only I didn’t know what to call myself. Today, I know who I am, and more important, I know

why

I am.

It was that

why

that mattered: “As a child I had a knack for getting in trouble. As an adult I look forward to telling the world my sexuality. I am willing to take all my critics on. I have appeared on television and radio, major newspapers, and adult fetish magazines. I have spoken at four different universities in Southern California. I also produce videotapes that I sell to my fellow crush-freaks for masturbation purposes. Trouble comes to town and his name is Jeff Vilencia!”

30

When Bill Clinton signed H.R. 1887 into law on December 9, 1999, he issued a statement instructing the Justice Department to construe the act narrowly, as applicable only to “wanton cruelty to animals designed to appeal to a prurient interest in sex.”

31

In the years since, perhaps wary of the legislation’s frailty, prosecutors have used it only three times. On each occasion—and contrary to Clinton’s directive—they wielded it

against distributors of dog-fighting videos. In July 2008, a federal appeals court struck down the law, agreeing with Robert Scott that the First Amendment does not allow the government to ban depictions of illegal conduct (as opposed to that conduct itself). In October 2009, the Supreme Court heard an appeal from the government backed by animal rights groups.

32

No matter the fate of H.R. 1887, for Jeff Vilencia there is no going back from those few hot weeks in the fall of 1999. Jeff tells me how his radio and TV interviews were edited to make him monstrous, how he tried to play the unedited tapes for his family but they believed only the broadcast versions. He tells me how his niece—in the name of her new baby—led his mother on a tour of websites that featured crush videos or specifically targeted him. “I lost friends, my brothers and sisters … I mean, it was just a horrible ordeal. I was almost isolated. I mean, I had no friends, no one wanted to talk to me, you know, and I just thought … you know …” He trailed off. He tells me how he quit video making entirely. “I just got to the point of giving up on life.” He tells me how it’s since been impossible to find a job because these days employers automatically Google their applicants.

So here we are on the featureless patio outside that suburban Starbucks, and he’s telling me that he learned two things from all this: that women are “really cruel bitches” and that “perversions are best left in the closet, buried in the dark.” He’s telling me about the men who were inspired by his example to come out to their girlfriends and wives and how in all cases their lives fell to pieces. And he’s telling me that he needs love too and that now he has someone who gives it to him but doesn’t want him talking about all this anymore. And he checks my watch nervously, leans back in his chair, looks out across the parking lot, sighs, and says softly: “Seems like a dream, man …”

Go to YouTube, search for “crush videos,” and see what you get. There’s a lot up there. Short, poor-quality home videos of women stepping on crickets, worms, snails, lots of squishy soft fruit. Some of the clips have

had tens of thousands of views, most have a few thousand, one has a couple of hundred thousand. It’s a long way from the underground trade of expensive Super 8 film in the 1950s and ’60s and even from the back-of-the-porn-mags sales in the ’80s and ’90s. If YouTube doesn’t meet your need, it’s easy to find longer and more professional product on the many specialist websites that are trading entirely openly despite Gallegly’s legislation.

Gallegly himself allowed for this future. At one point in the debate on H.R. 1887, he took the floor to clarify a crucial point. “This has nothing to do with bugs and insects and cockroaches,

things

like that,” he told his colleagues. “This has to do with

living animals

like kittens, monkeys, hamsters, and so on and so forth.”

33

For a moment, there’s something on which everyone can agree. There are animals that matter, and there are things that don’t. And then Gallegly draws breath, and before you know it, he’s off again about Ted Bundy, the Unabomber, and the safety of our children.

emptation

1.

It was August 1877, and Baron Carl Robert Osten-Sacken, a Russian aristocrat recently retired as the czar’s consul general in New York, had stopped for a few days at Gurnigel, “the well-known watering-place near Bern.”

1

The baron was forty-nine years old and at a turning point in his life. He would spend a year traveling in Europe before arriving in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where, once more in the New World but freed from imperial service, he would settle at Harvard’s famous Museum of Comparative Zoology, and spend the rest of his days pursuing his passion for flies. Some thirty years later, his obituarist would describe him as “the

beau ideal

of a scientific entomologist,” citing his mastery of relevant languages, his independence of means, his elevated social rank, his prodigious memory, exceptional observation skills, “almost perfect” library of works on the Diptera, and naturally, his impeccable manners.

2