India: A History. Revised and Updated (40 page)

Read India: A History. Revised and Updated Online

Authors: John Keay

Tags: #Eurasian History, #Asian History, #India, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #History

Indisputably the most elaborate and imposing rock-cut monument in the world, the Kailasa still triumphantly confirms the Balhara’s status as ‘one of the four great or principal kings of the world’. It also provides a further illustration of the Rashtrakutas’ attempt to appropriate the sacred geography of

aryavarta.

Mount Kailasa in the Himalayas is the earthly abode of Lord Shiva. The new Kailasa temple at Ellora, also wrought of

rock and also dedicated to Shiva, was designed to reposition Mount Kailasa in the Deccan and so, by implication, to make of the gentle Vindhya hills a Himalayas-in-the-Deccan which would be the northern frontier of the new

aryavarta.

Similarly and symbolically, to the new Kailasa was added a shrine with images of Ganga, Jamuna and Saraswati, the three river deities of

aryavarta.

King Dhruva, we learn, on his invasion of the north had ‘taken from his enemies their rivers’, a reference which could apply to the deities but seems more probably to mean that the Rashtrakutas actually ‘brought the waters of these streams back with them in large jars’. ‘So it seems clear that the Rashtrakutas, who had made Mount Kailasa appear in the mountain range north of their domains, also caused the rivers which had originated there, the rivers which defined the middle region of India, to appear in their empire in the Deccan.’

19

All empires, even those which would refashion the earth as well as rule it, must pass. Assailed in the south by the rising power of the Cholas and in the north by the Paramaras, erstwhile feudatories of the Gurjara-Pratiharas, the Rashtrakutas dwindled into insignificance in the late tenth century. The dream of a Deccan

aryavarta

died with them, although much further south something similar would imminently be attempted by the Cholas of Tanjore. They too would reach the Ganga, and they too would then laboriously haul its waters home to their own

aryavarta

at the mouth of the Kaveri river.

But in the interim northern India had been ravaged by the first Muslim incursions. Any attempt to transpose its sacred geography now looked less like sincere imitation and more like a desperate act of preservation. The real

aryavarta

had been violated, and the Cholas’ boast to have watered their horses in the mighty Ganga would merely echo that of a more formidable foe who cared nothing for the gilded fantasies and rock-cut conventions of early India’s imperial formations.

10

Natraj, the Rule of the Dance

c950–1180

THE LION OF GHAZNI

A

PART FROM

the Arabs’ conquest of Sind and their raids into Gujarat and Rajasthan, all in the early eighth century, no major confrontation with Islamic intruders is known to have taken place before the late tenth century. Indeed Hindu–Muslim relations may often have been amicable. The Rashtrakuta king is said to have afforded generous protection to Muslim merchants. As one of them put it, ‘none is to be found who is so partial to the Arabs as the Balhara; and his subjects,’ he added, ‘follow his example.’

1

Literal application of the

mandala

principle meant that the Rashtrakutas saw the Gurjara-Pratiharas, their immediate neighbours in western India, as their obvious enemy; the immediate neighbours of this enemy, the Arabs of Sind, were therefore their natural allies. If no formal alliance is in fact recorded, it was probably not because the amirs of Mansurah and Multan were Muslims but because they were rarely in a position to render any worthwhile aid to India’s ‘king of kings’.

Similarly the Gurjara-Pratiharas, though undoubtedly considered hostile by the Arabs, cannot certainly be credited with any campaigns designed either to evict or contain them. As a title,

pratihara

does indeed mean a ‘door-keeper’ or ‘gate-keeper’. But by the dynasty so named it was said to signify their impeccable descent from the

pratihara

of Lord Rama’s city of Ayodhya. By the Rashtrakuta king, on the other hand, it was taken to mean that they were fit only to man the gates of his own relocated

aryavarta

.

Those to be kept out, it seems, were not just the Muslim rulers of Sind, but any other marauding neighbours, including Hindus like the kings of Kashmir. Around the year 900 a Gurjara feudatory in the Panjab was obliged to relinquish to Kashmir a sliver of territory in the vicinity of the Chenab river. Previously acquired by the empire-building King Bhoja, it

was apparently surrendered to preserve the rest of the Gurjara-Pratihara empire, an action which was likened by Kalhana, the author of an important chronicle of Kashmir, to that of severing a finger to save the rest of the body. East of the Panjab, no Muslim power was as yet even a remote contender for primacy in

aryavarta

, while westward, the thrust of Baghdad’s global ambitions had been redirected into Afghanistan and Turkestan. India’s so-called ‘bulwark of defence against the vanguards of Islam’, if there was such a thing, must be sought not in Kanauj beside the Ganga but in Kabul beyond the Indus.

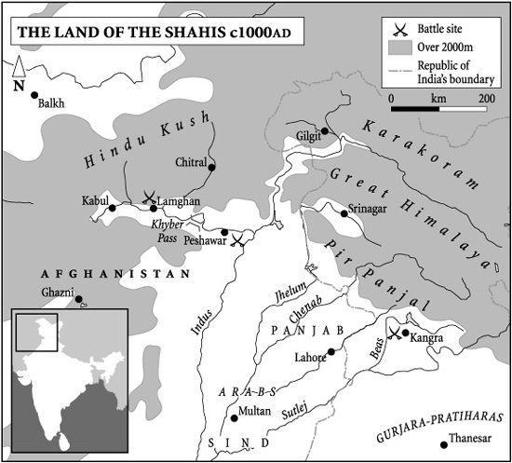

There, in a kingdom reminiscent of the Kushanas’ Gandhara which straddled the north-west frontier and extended deep into Afghanistan, an Indian dynasty known to history as the Shahis had risen to prominence in the mid-ninth century. The name ‘Shahi’ clearly derives from the ‘king-of-kings’ title (

shah-in-shahi

) adopted by the Kushana in imitation of Achaemenid practice. Al-Biruni actually links the Shahis with the great Kushana emperor Kanishka, and this may not be totally fanciful since Hsuan Tsang in the seventh century had found the kings of the Kabul region to be still devout Buddhists. Latterly a palace revolution not unlike that engineered by Chach in Sind had brought about the downfall of the last Buddhist king and the succession of his brahman minister, Lalliya. It is the latter and his successors who comprise the Hindu Shahis, and in the late ninth century great was the fame of these far-flung Indian dynasts.

According to Kalhana ‘their mighty glory outshone the kings in the north just as the sun outshines the stars.’ He likened their capital to

aryavarta

in that it was hemmed about not by the Himalayas and the Vindhyas but by the

Turuskas

(Turks) and other equally formidable barbarians; within its borders, however, kings and brahmans found sanctuary. In the Panjab the Shahis jostled with Gurjara, Kashmiri and Sindi rivals, sometimes as allies, sometimes as enemies; while in Afghanistan their feudatories clung to considerable territories to the south and east of Kabul. These latter were the first to go, and in 870 Kabul itself was captured. In Afghanistan the Shahis retained only Lamghan or Lughman, which was that part of the Kabul river valley west of Jalalabad. But in the Panjab they consolidated their kingdom and established a new capital first at Hund or Ohind near Attock on the Indus and later, seemingly, at Lahore.

Meanwhile in Afghanistan those territories seized from the Shahis in the name of Islam invited the interest of would-be adventurers from further afield. Muslim conquests in eastern Iran and Turkestan had brought a host of Turkic peoples into the Islamic fold. Arab influence there was already on the wane, and in central Asia Baghdad’s authority had been eclipsed by that of Bukhara, whose Safarid and Samanid dynasties zealously carved out Islamic empires north of the Hindu Kush. In 963 Alptigin, an ambitious but out-of-favour Samanid general, crossed the Hindu Kush from Balkh and seized Ghazni, a strategic town on the Kabul–Kandahar road. Himself once a Turkic slave, Alptigin was succeeded in 977 by Sabuktigin, also an ex-slave and also a Turkic general whose elevation owed nothing to scruple. Sabuktigin’s kingdom-building ambitions brought him into conflict with the Shahis. In c986, ‘girding up his loins for a war of religion’, says the Muslim historian Ferishta, ‘Sabuktigin ravaged the provinces of Kabul and Panjab’.

Jayapala (Jaipal), the Shahi king, responded with the utmost reluctance. ‘Observing the immeasurable fractures and losses every moment caused in his states … and becoming disturbed and inconsolable, he saw no remedy except in beginning to act and to take up arms.’ This he did with some success, mustering a vast army and conducting it across the north-west

frontier to confront Sabuktigin from a fortified position amongst the crags of Lughman. Hindu and Muslim then joined in battle.

They came together upon the frontiers of each state. Each army mutually attacked the other, and they fought and resisted in every way until the face of the earth was stained red with the blood of the slain, and the lions and warriors of both armies were worn out and reduced to despair.

2

The battle, in other words, ground to an indecisive standstill. Foremost amongst the lions of Ghazni was Mahmud, the eldest son of Sabuktigin and a man with an awesome reputation in the making. Yet even he, the future conqueror of a thousand forts, could see no way of overcoming Jayapala’s position. Then, supposedly thanks to a bit of Islamic sorcery, the weather intervened; seemingly it was the beginning of the Afghan winter. A contemporary chronicler says it was more like the end of the world: ‘fire fell from heaven on the infidels, and hailstones accompanied by loud claps of thunder; and a blast calculated to shake trees from their roots blew upon them, and thick black vapours formed around them.’

3

Jayapala thought his hour had come. He immediately sued for peace while his troops, unaccustomed to the cold and ill-equipped to bear it, embraced the prospect of a quick withdrawal. Sabuktigin, pleasantly surprised by this development, settled for an indemnity of cash-plus-elephants and a few choice fortresses. Finally, in a scene rich in instruction for nineteenth-century imperialists and twentieth-century superpowers, the benumbed and humiliated infidels trailed through the fearful gorges of the Kabul river back down to India as Sabuktigin’s jubilant

mujahideen

watched from their crags.

Jayapala did not apparently regard this as a defeat. His troops had given a good account of themselves and for once it was the elements, rather than the elephants, which had deprived them of victory. When safely back in the Panjab, he therefore treated Sabuktigin’s envoys as hostages. The Ghaznavid responded by again ‘sharpening the sword of intention’ and swooping on the luckless and now undefended people of Lughman. In a taste of things to come, the Muslim forces butchered the idolaters, fired their temples and plundered their shrines; such was the booty, it was said, that hands risked frostbite counting it.

To avenge this savage attack, Jayapala again felt obliged to take up arms. Al-Utbi, young Mahmud’s secretary, says that the Shahi king assembled an army of 100,000, but we have only the much later testimony of the historian Ferishta that it included detachments from Kanauj, Ajmer, Delhi and

Kalinjar. If so, it represented a notable mobilisation of those erstwhile feudatories of the Gurjara-Pratiharas who would claim rajput descent. Kanauj seems to have been still in Pratihara hands; Ajmer (in Rajasthan) was in territory ruled by the Chahamana rajputs; Delhi, founded in 736 but still a place of little consequence, belonged to the Tomara rajputs of Haryana; and Kalinjar (west of Khajuraho in Madhya Pradesh) was the stronghold of the rising Chandela rajputs. Additionally Jayapala himself may have been a rajput of the Bhatti clan, since his name and those of his successors, all ending in ‘-pala’, have been taken to indicate a break with the earlier Shahis who were brahmans.

Sabuktigin, surveying this host from a hilltop, was not impressed. ‘He felt like a wolf about to attack a flock of sheep,’ says al-Utbi. The Ghaznavid horse were divided into packs, each five hundred strong, which circled and swooped on the enemy in succession. Evidently the battle was this time being fought in the open, probably somewhere in Lughman, and under a merciless sky. The Indian forces, ‘being worse mounted than the cavalry of Subuktigin, could effect nothing against them’, claims Ferishta. Close-packed and confused by the barrage of assaults, they were also suffering from ‘the heat which arose from their iron oven’, says al-Utbi. When satisfied that the enemy were well kneaded and baked, Sabuktigin’s forces massed for a concerted attack. So thick was the dust that ‘swords could not be distinguished from spears, nor men from elephants, nor heroes from cowards’. When it settled, the outcome was clear enough. The Shahi forces had been routed and those not dead on the field of battle were being butchered in the forest or drowned in a river. No mercy was to be shown: God had ordained that infidels be killed, ‘and the order of God is not changed’.

As well as two hundred elephants, ‘immense booty’, and many new Afghan recruits eager for a share of India’s spoils, Sabuktigin acquired by this victory the region west of Peshawar including the Khyber Pass. A foothold on Indian soil, this corner of the subcontinent would serve well as a springboard for more ambitious raids. These, however, were delayed. Sabuktigin next led his troops north across the Hindu Kush and, after a series of victorious campaigns in the Herat region, was recognised by the Baghdad caliph as governor of vast territories embracing all northern Afghanistan plus Khorasan in eastern Iran. He died in Balkh in 997 and was succeeded by his son Mahmud, who quickly secured his father’s conquests in central Asia.