India: A History. Revised and Updated (44 page)

Read India: A History. Revised and Updated Online

Authors: John Keay

Tags: #Eurasian History, #Asian History, #India, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #History

Yet if one returns to the Tanjore inscription, there is mention of neither pious nor commercial gains, only of military matters, of formidable defences overcome and of desirable booty secured. The ‘jewelled gates’ of Srivijaya and the ‘heaped treasures’ of Kadaram were what mattered. Plunder once again proves to be the constant factor behind Chola expansion.

Rajendra’s reign lasted thirty-three years, during which time, we are told, he ‘raised the Chola empire to the position of the most extensive and most respected Hindu state of his time’.

19

The fact that his most ambitious conquests were hurried forays in search of booty and prestige, that he failed to subdue his immediate neighbours in the Deccan, and that even Sri Lanka would have to be evacuated by his successors in no way discredits this statement. On such doubtful foundations lay most other claims to extensive empire and dynastic regard in pre-Islamic India.

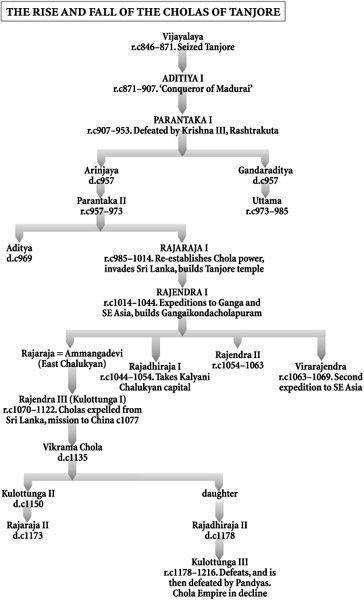

FISH-RICH WATERS

The Cholas’ supremacy in the south would last until the early thirteenth century. Territorially their sway was much reduced with the loss of Sri Lanka in c1070, the gradual reassertion of Pandyan sovereignty from about the same time, and the ebb and flow of fortune in the almost continuous hostilities with the Later Western Chalukyas and other Deccan powers. But the Cholas’ international prestige remained intact. A seventy-two-man Chola mission reached China in 1077. In 1090 the Chola king received another deputation from Kadaram in connection with the affairs of the Buddhist establishment at Negapatnam, and in subsequent years diplomatic exchanges are recorded with both of south-east Asia’s master-building dynasties, the Khmers of Angkor and the Burmans of Pagan.

The Cholas themselves continued to build, although the sites were fewer and the pace slackened as resources diminished. The classic example is the Nataraja temple of Chidambaram. Nothing if not transitional, its construction spanned several reigns from c1150 to 1250. Its profile marries ‘a compendium of the entire Chola style’ with cardinal features of later south Indian architecture, most obviously the colossal

gopuras

or gateways. In that the Chidambaram temple seems to have replaced those of Tanjore and Gangaikondacholapuram as the dynasty’s symbolic focus, its varied iconography and extremely confused layout (‘it is still impossible, for example, to determine its original orientation’

20

) may be taken as an apt commentary on the uncertain aspirations of the later Cholas.

But they did at least survive; and any continuity in a period of such dismal confusion is welcome. The historian who looks for a classic example of

matsya-nyaya

, that ‘big-fish-eats-little-fish’ state of anarchy so dreaded in the

Puranas

, need look no further than India in the eleventh to twelfth centuries.

Dharma

’s cosmic order appeared utterly confounded and the geometry of the

mandala

hopelessly subverted. Lesser feudatories nibbled at greater feudatories, kingdoms swallowed kingdoms, and dynasties devoured dynasties, all with a voracious abandon that woefully disregarded the shark-like presence lurking in the Panjab.

Even there the Muslim descendants of Mahmud, though they clung to their patrimony with a rare constancy, seemed to be succumbing to the spirit of a senseless age. Seldom did a Sultan succeed without a major succession crisis and a horrific bloodbath. Since two of Mahmud’s sons had been born on the same day but of separate mothers, this was initially understandable. But thereafter it became a habit, and the Ghaznavids’ Panjab kingdom was rent with internal dissension. Externally, sporadic raids into neighbouring Indian territories produced more treasure but few political gains. The reign of Masud, Mahmud’s immediate successor, is said to ‘mark a phase of total strategic confusion, as far as his relations with India go’.

21

They went not far, nor for long; Masud was overthrown and killed in a palace revolution. Meanwhile, beyond the Hindu Kush, the Ghaznavids’ once-extensive territories were subject to steady encroachment by the Seljuq Turks and others. The loss of Khorasan in c1040 had the effect of shifting the focus of the shrinking empire from Afghanistan to India. Lahore virtually replaced Ghazni as the capital, which latter city, once the pride of the dynasty, was now held on sufferance and, after several devastating raids, irrevocably lost in c1157. A few years later it changed hands yet again. No longer an epicentre of empire, its principal charm was now as a strategic gateway to the Muslim kingdoms in Sind and the Panjab.

The new lords of this much-diminished Ghazni were complete outsiders from the remote region of Ghor in central Afghanistan. Warlords of possibly Persian extraction, they would nevertheless continue their presumptuous

encroachment. After several incursions across the north-west frontier, in 1186 they would overthrow the last of Mahmud’s successors. Lahore thus fell to the Ghorids; and their leader Muizzudin Muhammad bin Sam saw no reason to stop there. Determined to succeed where both Alexander and Mahmud had failed, this ‘Muhammad of Ghor’ would press on, east and south, to cruise with devastating effect in the fish-rich waters of the Indian

matsya-nyaya

.

It was not just a case of India being hopelessly fragmented. A discouraging prospect for the political historian, the eleventh to twelfth centuries have won yet more disgusted comment from social and economic historians.

Never before was land donated to secular and religious beneficiaries on such a large scale; never before were agrarian and communal rights undermined by land grants so widely; never before was the peasantry subjected to so many taxes and so much sub-infeudation; never before were services, high and low, rewarded by land grants in such numbers as now; and finally never before were revenues from trade and industry converted into so many grants.

22

It reads like a prescription, if not for revolution, then certainly for a reformation. According to this diagnosis, economic collapse, social oppression and caste discrimination went hand in hand with political fragmentation. India was bracing itself for a renewal of the Islamic challenge by squandering the resources, oppressing the people and pulverising the authority on which any effective resistance must depend. Indeed the triumph of an alternative dispensation which, like that of Islam, promised social justice, the equality of the individual and firm government would seem to be assured. Instead of warring for centuries to win minority acceptance, Islam should have won spontaneous adoption.

That it did not suggests that the situation was not that dire. Economic activity may have declined, but evidence of social protest is lacking. Instead there are many examples of contemporary rulers who enjoyed great repute in their lifetimes and have been the subjects of popular romance ever since. Even from the murky mêlée of competing dynasts in north and central India a few figures of striking stature emerge, none more revered than the great ‘philosopher-king’ Bhoj of Dhar.

Not to be confused with the ninth-century Pratihara King Bhoj (or Bhoja) of Kanauj, this eleventh-century Bhoj belonged to a clan of the Paramaras who had once been feudatories of the Rashtrakutas in Gujarat. Claiming

ksatriya

(or rajput) status like so many of their contemporaries, the Paramaras had asserted their independent rule in Malwa in the mid-tenth

century when both the Rashtrakutas and the Pratiharas were slipping into terminal decline.

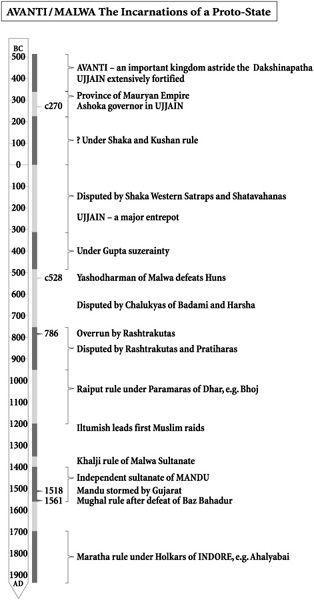

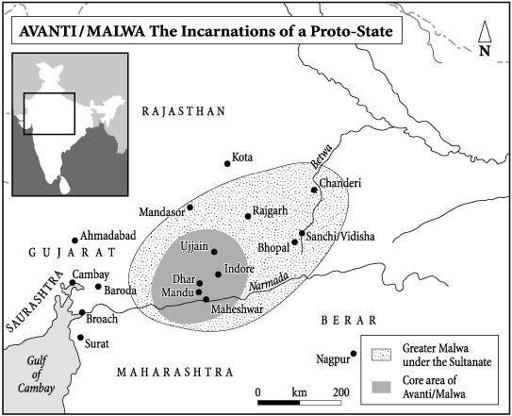

As their capital they chose Dhar, now a small town between Ujjain and Mandu in Madhya Pradesh. Ujjain, beside the Sipra river, was the ancient centre of Malwa where Ashoka had allegedly misspent much of his youth, while Mandu, now a heavily fortified but eerily deserted headland high above the Narmada, would become the redoubt of Malwa’s next rulers. Such a scatter of regional centres within a small radius is not unusual. In the progression from hallowed but indefensible Ujjain to upland Dhar to near impregnable Mandu one may detect a response to changing times.

Bhoj succeeded to the throne of Dhar in or about the year 1010 and seems to have reigned for nearly fifty years. He was therefore an exact contemporary of the Chola, Rajendra I. From his uncle and his father, both bellicose

digvijayins

, he inherited suzerain claims over a host of rival kings and sub-kings scattered throughout Rajasthan, central India and the Deccan. They certainly did not include the ‘Keralas and the Cholas’, whose bejewelled diadems are nevertheless said, in a by-now threadbare cliché, to have coloured his uncle’s lotus feet. But amongst the many to whom these claims were unacceptable were just about every other contemporary dynasty including the Chandelas of Khajuraho, their formidable Chedi and Kalachuri neighbours, the reborn Western Chalukyas of the Deccan, the Solankis of Gujarat, and numerous other incipient rajput kingdoms plus assorted minor potentates in Maharashtra and on the Konkan coast.

Lumbered with such a contentious inheritance, the youthful Bhoj felt obliged to take the field on his own

digvijaya

. The results were mixed, his successes being much contradicted and his failures quickly reversed. Generally speaking, in Gujarat and Rajasthan he seems to have held his own but in the Deccan he made little progress. This was despite an anti-Chalukyan alliance with the Cholas and a legacy of exceptional bitterness left by his uncle, who had been captured, caged and executed by the Chalukyas. ‘His head was then fixed on a stake in the courtyard of the royal palace and, by keeping it continually covered with thick sour cream, [the Chalukya] gratified his anger.’

23

Such an outrage rankled deeply with the Paramaras, and may explain Bhoj’s obsession with chastising the Chalukyas.

In this he not only failed but, at one point, was surprised by a Chalukyan raid and had to flee from his beloved Dhar. The capital, though said to have been devastated, must have been speedily regained and then restored, for it is as ‘Dharesvara’, the intellectual magnate and ‘lord of Dhar’, that Bhoj is principally remembered. Compared to the Cholas or the Pratiharas, claims as to his military prowess ring somewhat hollow. But if military success was an essential attribute of kingship, so too was scholastic attainment and patronage. In this respect Bhoj outshines even Harsha’s intellectual genius as portrayed in Bana’s

Harsa-carita

; for whilst to Harsha have been attributed works which he certainly did not write, ‘we have no real knowledge to disprove Bhoj’s claim to polymathy exhibited in a large variety of works.’

24

These range over subjects as various as philosophy, poetics, veterinary science, phonetics, archery, yoga and medicine. ‘To study Bhoj is to study the entire culture of the period.’ Dhar seems to have been transformed into a veritable Oxford, with its palaces serving as common rooms of intellectual discourse and its temples as colleges of higher education. Other kings, contemporary and subsequent, could hardly contain their admiration. ‘Bhoj was such a versatile personality and left such a deep impression … that even the pro-Chalukya chronicle, the

Prabandhacintamani

, felt constrained to conclude its account of Bhoj with the words: “Among poets, gallant lovers, enjoyers of life, generous donors, benefactors of the virtuous, archers, and those who regard

dharma

as their wealth, there is none on the earth who can equal Bhoj.”’ Other rajput kings would achieve greater popular celebrity as heroes of the martial ethos which their

ksatriya

status enjoined. Bhoj’s legacy was no less substantial. As his own eulogy succinctly puts it, ‘he accomplished, constructed, gave, and knew what none else did. What other praise can be given to the poet-king Bhoj?’

25