Ideology: A Very Short Introduction (Very Short Introductions) (17 page)

Read Ideology: A Very Short Introduction (Very Short Introductions) Online

Authors: Michael Freeden

In a broader sense, post-Marxists and poststructuralists use ideology as an abstract technical term. It has itself become a signifier with no clear meaning. Its purpose is importantly to warn scholars that they are now entering an area in which their critical faculties have to be engaged (not, as with Marx, an area to be abolished). But ideology retains its negative Marxist connotations; it is the obfuscated way in which reality is presented to all, and it forces people to inhabit a world of constricted structures, or of psychological necessity, from which escape routes are badly marked and usually culs-de-sac. A new generation of critics of ideology has been born, but they have little to offer in return for their discovery of its bleak function. No utopias, no solutions, only the awareness that we move from one make-believe world to another and that, perhaps, we can at least aim for the make-believe that does not fundamentally dehumanize those who hold it. This resistance to empiricism, to sense-evidence other than the evidence of language itself, makes poststructuralism an uneasy partner for the projects of most social scientists and historians.

The poststructuralist view of ideology is radical and the view it offers is austere. Its strength lies in its refusal to take any fact, any opinion, any framework, for granted. At the same time, this is a source of weakness among some of its less sophisticated practitioners. The possibilities of discourse in any society are limited, as we have seen, by its own history, and by the cultural constraints that block off some discursive interpretations of the political world and make several of them more challenging and

interesting than others. Nor is it the case that all articulated discourses are hegemonic. Several discourses may compete with each other at any point in time or space. That possibility is obscured by the post-Marxist preference for the Marxist convention of referring to ideology in the singular. Of course, that too is a discursive construct that makes us understand ideology in a particular way – something that, one suspects, discourse analysts would be only too happy to concede.

Stimuli and responses: seeing and feeling ideology

So far I have dealt with ideology as found in written and spoken language, in texts and utterances. We now have to take on board three further themes. First, ideology appears in many non-verbal forms. Second, even as textual discourse, ideology includes metaphors and stories that are not directly decodable as political language. Third, ideology concerns not only the rational and the irrational, the cognitive and the unconscious, but the emotional as well.

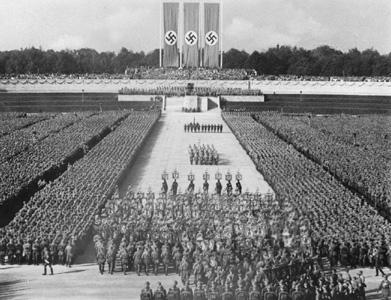

Throughout history ideologies have been transmitted through visual and pictorial forms. Over the past century, more than ever, with the advent of film and television, of the mass production of art and advertising, visual messages have become a striking and efficient way of conveying a political statement, insinuation, or mood. The Romans already knew about the dramatic sense of the visual, so chillingly and forcefully replicated in the Nazi Nuremberg rallies. The symmetrical choreography of the serried ranks, the inflammatory rhetoric of a leader surrounded by giant emblems, the aural impact of the roar of ‘Sieg Heils’ – all communicated with immediate effect some of the core Nazi ideas: the power of the undifferentiated mass, the relationship of leader to people, the militarization of the national will, the

coordination and unison of popular expression. These ideas were absorbed through head and gut simultaneously, and the experience of participating in this massive ritual must have been unforgettable.

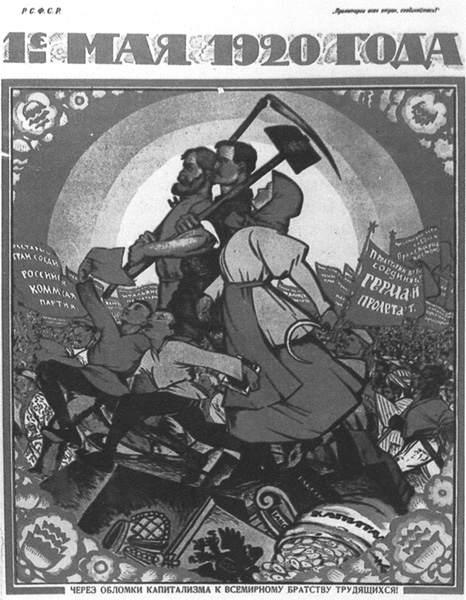

Pictures are central to all of the major ideological families – the dove of peace is a liberal internationalist symbol; the socialist movement has privatized the colour red, politically speaking; Soviet communists used posters and statues of giant workers heroically brandishing their implements of toil; and British conservatives capitalized on bulldogs and Winston Churchill’s cigar-chomping face when they wished to indicate tenacity and the will to fight and triumph. But visual images, still or moving, may be subtler than that and not directly associated with the main ideological families. London Underground posters of rolling green countryside, international charities’ gruesome photographs of people being tortured, architectural structures of public buildings invoking awe or aesthetic interest, the choice of which skin colour to display when pictures of policemen are used for job recruitment, carry political messages as well.

13. A Nazi Nuremberg rally

.

Many visual images may be seen as artistic technologies designed deliberately, or serving unintentionally, to disseminate ideological messages. To be successful in that role they must possess certain features. One is simplicity. If political texts aimed at mass consumption are simplifications – through sound bites and slogans – that is even more the case for most pictorial representation. Icons, signs, and logos are ways of impressing on someone an easily digestible set of meanings. Think of the communist hammer and sickle, combining force with earthy labour. They also need to be salient to the eye, standing out from other information. Think of a flag flying over an embassy, a haven for its nationals in a foreign field. A third feature is memorableness – the length of time in which their impact is retained. The image needs to operate as an anchor and base for a range of repeated associations, reinforcing the ideological message. Think of Lord Kitchener’s eyes and finger

picking you out from the crowd: ‘Your country needs you!’ A fourth characteristic is whether it is aesthetically pleasing or disturbing. Anything but blandness will help to lure the attention of the onlooker. Think of the photograph of the little Vietnamese girl fleeing from the napalm bombs. Those who might complain that this is merely packaging rather than content miss the point. Because the mobilization of support is crucial to the function of ideologies, good packaging may break the ice, penetrating the literacy barrier that would deter many people from paying attention to a more detailed text. Finally, stark visual images are useful in triggering primitive emotional reactions – raw responses that get translated into action more quickly, without being distilled through the medium of reflective evaluation.

Visual images have of course been augmented to a high order of magnitude through the development of mass communications. The mass media proffer a degree of penetration inconceivable in the past, and hence enhance the potential for mobilization that ideologies carry. It is no accident that fascist totalitarianism – an ideology that thrived on its permeation of all aspects of social life – found its most efficient form by drawing on the resources of the highly industrialized and bureaucratized Germany. Pictures, films, rituals, even speeches in which the form of delivery outweighs the content (consider Hitler’s rhetorical skills in whipping up mass enthusiasm through rhythm and pitch) are the equivalents of fast food: produced in haste, packaged with maximum allure, and consumed with a short-term effect in immediate thrill or awe, but with questionable long-term benefits for one’s body. Indeed, the shorter shelf-life of advertisements, commercials, and posters demonstrates that ideologies, like politicians, tend to prefer immediate impact to distant gains. Memorability may frequently be sacrificed for other advantages.

14. A Bolshevik poster celebrating the First of May, 1920

.

Visual symbols also discourage the two-way flow of debate and modification that occurs, on the morphological view, in ideologies. There is less movement of the kind, noted in

Chapter 4

, from the

periphery to the core, which produces much of the internal flux of a supple ideology. Pictures, posters, advertisements are finished end-products. True, a visual representation may excite a strong reaction, positively or negatively, and, of course, a range of varying interpretations. But because its symbolic representation comes in forms that constantly accost our eyes and swamp our vision, unlike texts that we have to seek out deliberately (the exception would be a

slogan), the reaction rarely takes the form of trying to alter it directly. We do not get back to the artist and ask for the painting or poster to be redone in the way that we continuously grapple with certain political texts we want to replace or modify – for example, amending a constitution. People have been trained to challenge and alter written and spoken texts far more proficiently than they can argue with images, because linguistic skills are much more important in the public cultures we inhabit, and because ideas are first and foremost transmitted through language. But even the visual arrangement of texts carries messages of its own: the decision which headline should be above the fold on page 1 of a newspaper, and its typeface size and design, indicate the degree of significance readers should attach to what follows underneath it. Nor are visual images the equivalent of ideological systems. They are rather modules, micro-units, or segments that pack a punch by releasing a concentrated message into the systems they inhabit.

A grey area exists between the use of language to convey political arguments and prescriptions, and the use of metaphor, which often works by appealing to imagery from another walk of life (‘a melting-pot’; ‘the promised land’; ‘the father of the nation’, ‘the corridors of power’). That is matched by the further devices of myth and story. Both are enjoyable ways of consuming ideological viewpoints. They offer attractive and imaginative packages for key social ideas, heavily disguised as forms of verbal entertainment. Alternatively, they may be viewed as defining narratives, lovingly preserved by societies that pass them on from generation to generation as a valued cultural heritage. Machiavelli’s recall of Romulus to illustrate the virtues of the Roman republic, the pioneers that trekked across the American continent, the voyages of the Prophet Muhammad, the legends of King Arthur, and the Bible have all been excavated and replicated to serve foundational ideological ends. These texts frequently evoke not ideas in our minds but pictures; they serve as surrogate visual images.

The evocative nature of imagery and of myth brings us back to the feature I touched on in

Chapter 5

: the importance of emotion and feelings in ideologies. The study of ideology recognizes that emotions perform a dual role. On an instrumental level they are employed as apparatuses of ideological argument or messaging. On a more profound level, ideologies are the main form of political thought to accept passion and sentiment as legitimate, indeed ineliminable, forms of political expression. Ideologies reflect the fact that socio-political conduct is not wholly or merely rational or calculating, but highly, centrally, and often healthily emotional. Utilitarian and other philosophical schemes that bypass this vital facet of being human, and of interacting with others, are in danger of impoverishing and caricaturing the realm of the political.

Being emotional, and addressing the emotions, are not flawed ways of thinking about politics. True, in their extreme forms they cause collectivities to act as in a frenzy – mob-rule and lynching spring to mind. But giving vent to emotions is not necessarily being irrational. The German sociologist Max Weber famously distinguished between instrumental and value rationality: the first used a means-end rationality as the criterion by which to judge the most cost-effective set of political goals to pursue; the second adhered to a given value at whatever cost it produced. The non-negotiable assumptions we have observed at the basis of any ideology are examples of value rationality. The point however is that they are usually dressed in a protective emotional coating. Even liberals wax lyrical in extolling the virtues of liberty and call for crusades for freedom. Before analytical philosophers neutered the concept of justice, liberals could talk of the ‘enduring glow’ its passionate pursuit kindled. Terms such as inspiration, certainty of conviction, compassion, sympathy, and the stirring up of the public imagination can all be found in liberal discourses, but liberals all concurrently insist on retaining a critical cool head in assessing and channelling those emotions.