Ideology: A Very Short Introduction (Very Short Introductions) (16 page)

Read Ideology: A Very Short Introduction (Very Short Introductions) Online

Authors: Michael Freeden

Much discourse theory has developed a

critical

edge that takes us back to Marxist theories of ideology. Discourses become then just the latest way of portraying ideology’s pernicious effects – linguistic frameworks in which individuals and groups are trapped, in which communication serves the purpose of concealment and deceit, in which repression and antagonism breed and are perpetuated, and in which one’s utterances and texts are mistakenly assumed to be authentic expressions of one’s own ideas, rather than implanted from outside. Even seemingly less harmful discourses are exposed for what they really are:

contingent norms of conduct and of thought, masquerading as normal and even universal rules of human interaction. Discourse is transformed from an innocuous fact of social life to a contrivance that permeates human existence by means of the cultural constraints it imposes. As Michel Foucault phrased it, discourse is power, thus extending the sociological insight through which Marx had viewed ideology.

Identity, however, has come to supplant class as the arena in which group destinies are moulded. The struggle over the control of one’s identity, resisting the imposition by others of a flawed or irrelevant identity, pervades social power relationships. Meena regards herself primarily as a biochemist, others define her as a Hindu. Robert delights in being a voluntary community worker, others perceive first and foremost a black male. While the aim of discourse analysts is to reveal the nature of the encumbrances that such communication generates, occasionally in great technical detail, the theoretical stance behind that aim can occasionally verge on the nihilistic. Language is seen as the container of infinite possibilities, and there is no fixed archimedal point to direct us towards truth, correctness, or knowledge.

Any

description of Meena is restrictive and misleading of what she is. Change and flux, not fixity, become the new order. When this approach is pushed to its limits, language becomes the only reality. Reality is simply what a discourse ordains reality to be, a discursive construct, and objectivity is a chimerical pursuit even for the scholar.

What of this is relevant to theorizing about ideology? For those who see both discourse and ideology as primarily about power relations, discourses are the communicative practices through which ideology is exercised. For those who see language as the medium through which the world obtains meaning, discourse may replace, or partially depoliticize, the concept of ideology. But we may

reformulate that relationship: ideology is one form of discourse but it is not entirely containable in the idea of discourse. To begin with, discourse analysts abandon the representation of reality and plump conclusively for the construction of reality. Ideologies engage in both. They interact with historical and political events and retain some representative value. But they do so while emphasizing some features of that reality and de-emphasizing others, and by adding mythical and imaginary happenings to make up for the ‘reality gaps’. A constant feedback operates between the ‘soft’ ideological imagination and the ‘hard’ constraints of the real world.

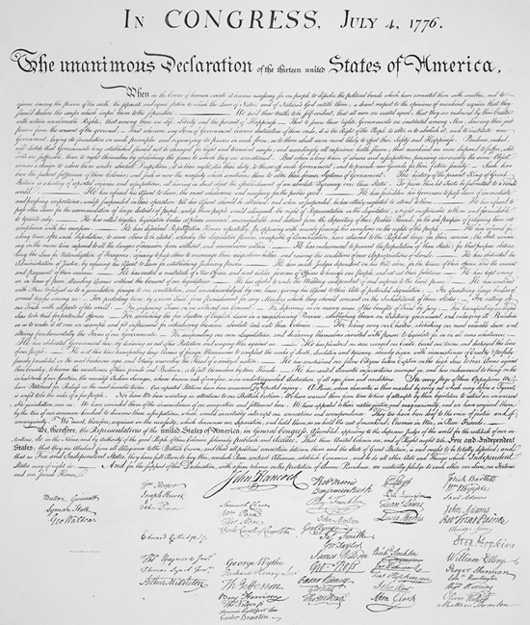

The complexity of analysing a discourse can be illustrated by taking the famous passage from the American Declaration of Independence of 1776:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

A political philosopher might read this as a complex statement encompassing a number of philosophical assertions:

(1) the

universality

of certain fundamental human attributes;

(2) the extra-human

sanctification

of several essential goods;

(3) faith in the overriding power of

truth

;

(4) the similar

comparative status

of human beings;

(5) the bestowing of entitlements on

individuals

.

It is an account of how things are – political philosophers might call these moral facts – but also an indication of the concrete practices that will result from this view of the world.

A critical discourse analyst may give the passage a rather different reading:

12. The American Declaration of Independence

.

(1) It constructs a human identity that

refuses to recognize differences

, while signalling that anyone who does

not accept the truths

of the passage places himself or herself beyond the pale of humanity.

(2) It is a manifestation of

power

inasmuch as it serves the aims of the founders of the USA and implicitly justifies mobilizing the use of force in the name of their ideals, while explicitly shaping human beings in a preferred image.

(3) It attains these ends by using

linguistic strategies

such as the inclusive ‘we’ and the capitalization of key words.

(4) It tells a story, a brief

narrative

, about how we came to be what we are from the moment of our birth, and it is phrased in vocabulary that an 18th-century American reader might find congenial, and that a contemporary American reader could identify with in broad terms.

(5) It is

gendered

, privileging men.

An analyst of ideology would agree with most of the discourse analysis, but would prefer to examine the more directly political implications of the passage and the intricate micro-structures that reveal specifically ideological decontesting techniques. The work consciously or unconsciously performed by the passage would include:

(1) ruling out certain beliefs from ever being intellectually or rationally challenged, by

protecting

them with the impenetrable and non-transparent shield of self-evidence – as with the emperor’s new clothes, only a child or a fool would screw up the courage to query what is presented as inherently obvious and uncontentious;

(2) anchoring political beliefs in powerful

cultural support

systems, in particular an appeal to a divine entity as the shaper and underpinner of the social order;

(3)

prioritizing

a particular set of human characteristics, namely one that maximizes unimpeded and vigorous individual pursuits, that assumes that individuals determine their own fates, and that describes them as possessing unassailable claims to precious social goods;

(4)

advocating

a system of human relations in which human differences are rendered unnatural;

(5)

impressing

the readers of the Declaration with a powerful rhetoric that drives home the significance of its messages, from the smooth confidence generated by a ‘declaration’ to the staccato enumeration of memorable and easily recognizable rights.

In addition the analyst of ideologies would need to establish the historical roots of the passage, and investigate whether that

successful contest over meaning vanquished in its wake all other attempts at decontestation. If so, how does the historical emergence of a dominant ideological variant co-exist with the assertion of discourse analysts that all meaning is a product of language alone? That assertion, central to what has been called the ‘linguistic turn’, suggests that linguistic polysemy and language games allow infinite possibilities of meaning, so that one meaning cannot conclusively be preferred over another. But does that not let the scholar off too lightly? On the alternative understanding advanced in

Chapter 4

, I have argued that ideological meaning is located at the meeting place between logical and cultural constraints. In ideological practice, permissible and legitimate meanings restrict the infinity of semantic options that the ‘linguistic turn’ postulates. In short, ideological meaning is a joint product of the degree of analytical rigour possessed by its formulators, of the linguistic flexibility of language, and of historical context. This may confirm its contingency but not its unlimited content.

Finally, discourse analysts occasionally treat language as a given within which options are barely available to the user caught in the game. The analysis of ideologies, in contrast, pays more respect to the role of individual choice and agency in shifting between disparate interpretations of the world and in refashioning those interpretations, particularly in a society that encourages ideological diversity. It pays more respect to the internal competitions over meaning, as befits a political standpoint. And it pays more respect to the pluralist and manifold nature of differences within an ideological field, while critical discourse theory tends to see the world as dichotomized between notions of the ‘self’ versus the ‘other’.

Post-Marxists and poststructuralists (sometimes bracketed under the broader label postmodernists) have recently given further impetus to the study of ideologies. Post-Marxists still regard

ideology as a means of sustaining collective power, but no longer on the basis of class alone. Poststructuralists are those who challenge the fixity and universality of existing linguistic and political terms and structures. Their method of analysis includes deconstruction – the breaking down of the implicit assumption that language represents reality. They endeavour to expose as misconceived the distinctions and oppositions that language establishes. In part, they follow parallel paths to some of the hermeneutic approaches discussed above, though their expositions are occasionally vitiated by an impenetrable jargon.

Among the more significant writings on ideology to have emerged from these intellectual movements are those of Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe. Going beyond Althusser’s position discussed in

Chapter 2

, they have disputed the Marxist priority of material base over ideational superstructure as being itself a discursive, rather than a real, relationship. All practices, they argue, are discursive in that they are human, optional, and contingent articulations of how we should understand the world – something entirely different from a claim about what the world is. The social order isn’t given; it is constructed or articulated. That produces only the

semblance

of fixity. This argument shies away from the notion of fragmented ideologies, for fragmentation entails the dissolution of a prior whole. Instead, wholes are themselves merely one, precarious, articulation out of an indeterminate number of potential combinations of ideas. Contingency in this case has no opposite (its opposite being necessity), because there is nothing necessary

in

discourse. However, there is something necessary

about

discourse – it is one of the central features of being human. That crucial factor prevents the perceived world from being meaningless or random to its viewers, although students of ideology will always challenge the permanence or absoluteness of the articulated, hegemonic, discourse.

In line with Marxist concerns, post-Marxists associate the analysis of ideology with the large issue of what ‘society’ itself is, and with

the parallel question of the identity of the individual or the ‘subject’. In particular, theorists such as Laclau and Mouffe have argued that the elusiveness of what we call ‘society’ requires the coinage of signifiers, representative words, to paper over the cracks and to invent stability and system where no such things exist. These they term a special category of signifier – ‘empty signifiers’ that do not represent an external reality but the absence of it. Thus when demonstrators march for ‘freedom’ it is far from clear what that would entail. Freedom here signifies something that societies cannot ever achieve in full, but the clarion cry ‘freedom’ produces the illusion that it exists and that a social order based on freedom is attainable. The awful truth that all societies are unfree has to be disguised.

That fanciful production of social order, according to post-Marxists, is the role of ideology. Because a free society is a chimera, ideologies are a necessary illusion. They cannot, contra Marx, wither away, without – as Slavoj Žižek has observed – creating the chaos and panic that staring into the void will cause. Ideology, nevertheless, is in a state of continuous renewal, as new signifiers need to be invented to keep up the masking process when old ones lose their bite. But the secret that has now been let out of the bag is that, in effect, there is nothing behind the mask. Žižek draws on French Lacanian psychoanalytical theory to contend that the horror of contemplating the unknowable leads people to weave imaginary webs, or fantasies, of what they claim can be known, and to fabricate harmonies where antagonisms reign. The dichotomy between the self and the other acquires a spectral, ghostly, status, because the ‘other’ is a mirage and the ‘self’ or the subject a temporary identity cobbled together for reasons of psychological comfort, bereft of the capacity for agency with which liberals endow the individual. On views such as these, ideologies cannot even be illusions or distortions. How can one distort truth if there

is

no truth, if reality pure and simple is inaccessible and even unimaginable? How can we know reality when what

we

perceive as reality is something else, filtered through

a mesh of symbols? However, if there is no truth, there can be no falsehood (= the corruption of truth). Instead of condemning ideology as false, it should be recognized as a powerful indicator of the ways in which people actually construe the world. It is a fact, we might say, that ideology (wrongly) presents discourse as objective fact. But because discourse is so ephemeral, ideology, according to Žižek, can never properly construct the stability that social life lacks.