I Have Landed (27 page)

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

In a final paragraph, Schröder offers his only statement about why such a procedure might enjoy success. The cure occurs because the same balsamic (comforting) spirit inheres in both the patient and the blood of his woundâand both must be fortified by the ointment. The weapon, I presume, must be treated because some of the patient's blood still remains (or perhaps merely because the weapon drew the patient's blood, and must therefore be cleansed along with the patient himself, in order to bring both parts of this drama back into harmony).

Oswald Croll (1560â1609), the inventor of this ointment, followed the theories of Paracelsus (1493â1541) in proposing external sources of disease, in opposition to the old Galenic theory of humors. In this major debate of pre-modern medicine, the externalists believed that “outside” forces or agents entered the human body to cause illness, and that healing substances from the three worldly kingdoms (animal, vegetable, and mineral, but primarily vegetable, as plants provided most drugs and potions) could rid the body of these invaders. The humoral theory, on the other hand, viewed disease as an imbalance among the body's four basic principles: blood (the sanguine, or wet-hot

humor), phlegm (the wet-cold humor), choler (dry-hot), and melancholy (dry-cold). Treatment must therefore be directed not toward the expulsion of foreign elements, but to the restoration of internal balance among the humors (bloodletting, for example, when the sanguine humor rises too high; sweating, purging, and vomiting as other devices for setting the humors back into order).

In Paracelsian medicine, by contrast, treatment must be directed against the external agent of disease, rather than toward the restoration of internal harmony by raising or lowering the concentration of improperly balanced humors. How, then, can the proper agents of potential cure be recognized among plants, rocks, or animal parts that might neutralize or destroy the body's invaders? In his article on Paracelsus for the

Dictionary of Scientific Biography

, Walter Pagel summarizes this argument from an age before the rise of modern science:

Paracelsus . . . reversed this concept of disease as an upset of humoral balance, emphasizing [instead] the external cause of disease. . . . He sought and found the causes of disease chiefly in the mineral world (notably in salts) and in the atmosphere, carrier of star-born “poisons.” He considered each of these agents to be a real

ens

, a substance in its own right (as opposed to humors, or temperaments, which he regarded as fictitious). He thus interpreted disease itself as an

ens

, determined by a specific agent foreign to the body, which takes possession of one of its parts. . . . He directed his treatment specifically against the agent of the disease, rather than resorting to the general anti-humoral measures . . . that had been paramount in ancient therapy for “removal of excess and addition of the deficient.” . . . Here his notion of “signatures” came into play, in the selection of herbs that in color and shape resembled the affected organ (as, for example, a yellow plant for the liver or an orchid for the testicle). Paracelsus's search for such specific medicines led him to attempt to isolate the efficient kernal (the

quinta essentia)

of each substance. [Our modern word

quintessential

derives from this older usage.]

This doctrine of signatures epitomizes a key difference between modern science and an older view of nature (shared by both the humor theorists and the Paracelsians, despite their major disagreement about the nature of disease). Most scholars of the Renaissance, and of earlier medieval times, viewed the earth and cosmos as a young, static, and harmonious system, created by God, essentially in its current form, just a few thousand years ago, and purposely

imbued with pervasive signs of order and harmony among its apparently separate realmsâall done to illustrate the glory and subtlety of God's omnipotence, and to emphasize his special focus upon the human species that he had created in his own image.

This essential balance and harmony achieved its most important expression in deep linkages (we would dismiss them today as, at best, loose analogies) between apparently disparate realms. At one level on earthâthus setting the central principle of medicine under the doctrine of signaturesâthe microcosm of the human body must be linked to the macrocosm of the entire earth. Each part of the human body must therefore be allied to a corresponding manifestation of the same essential form in each of the macrocosmic realms: mineral, vegetable, and animal. Under this conception of nature, so strikingly different from our current views, the idea that a weakened human part might be treated or fortified by its signature from a macrocosmic realm cannot be dismissed as absurd (the orchid flower that looks like the male genitalia, and receives its name from this likeness, as a potential cure for impotence, for example). Oswald Croll, in particular, based his medical views on these linkages of the human microcosm to the earthly macrocosm, and Schröder's

Pharmacopoeia

represents a “last gasp” for this expiring theory, published just as Newton's generation began to establish our present, and clearly more effective, view of nature.

At a second level, the central earth (of this pre-Copernican cosmos) must also remain in harmony with the heavens above. Thus each remedy on earth must correspond with its proper configuration of planets as they move through the constellations of the zodiac. These astronomical considerations regulated when plants and animals (and even rocks), used as remedies for human ills, should be collected, and how they should be treatedâhence, in Croll's ointment for wounds and swords, the requirement that cranial scrapings be collected under a good constellation, with the loving Venus, but not the warlike Mars or Saturn, in conjunction.

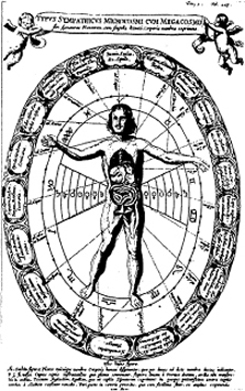

As a memorable example of this approach to healing under the doctrine of signatures and stable harmony among the realms of nature, consider the accompanying illustration from the last major work of scholarship in this tradition, so soon to be extinguished by modern scienceâthe

Mundus subterraneus

, published in 1664 by perhaps the most learned scholar of his generation, the Jesuit polymath Athanasius Kircher (who wrote an important ethnography of China, came closer than anyone else to deciphering the hieroglyphs of ancient Egypt, wrote major treatises on music and magnetism, and built, in Rome, one of the finest natural history collections ever assembled). In this figure, titled (in

Crollian fashion) “sympathetic types of the microcosm with the macrocosm,” lines radiate from each part of the human body to the names of plants (in the outer rim) that will cure the afflicted organs. To complete the analogies and harmonizations, the inner circle (resting on the man's head and supporting his feet) presents astronomical signs for the zodiacal constellations, while the symmetrical triangles, radiating like wings from the man's sides just below his arms, include similar signs for the planets.

Medicine under the doctrine of signatures as depicted by Athanasius Kircher in 1664. Each ailing part of the body can be linked to a healing plant, constellation of stars, and planet. See text for details

.

We rightly reject this system today as a false theory based on an incorrect view of the nature of the material world. And we properly embrace modern science as both a more accurate account and a more effective approach to such practical issues as healing the human body from weakening and disease. Viagra does work better than crushed orchid flowers as a therapy for male impotence (though we should not doubt the power of the placebo effect in granting some, albeit indirect, oomph to the old remedy in some cases). And if I get badly cut when slicing a bagel with my kitchen knife, and the wound becomes infected, I much prefer an antibiotic to a salve made of boar fat and skull scrapings that must then be carefully applied both to the knife and to my injury.

Nonetheless, I question our usual dismissal of this older approach as absurd, mystical, or even “prescientific” (in any more than a purely chronological sense). Yes, anointing the wound as well as the weapon makes no sense and sounds like “primitive” mumbo-jumbo in the light of later scientific knowledge. But how can we blame our forebears for not knowing what later generations would discover? We might as well despise ourselves because our grandchildren will, no doubt, understand the world in a different way.

We may surely brand Croll's sympathetic ointment, and its application to the weapon as well as the wound, as ineffective, but Croll's remedy cannot be called either mystical or stupid under the theory of nature that inspired its developmentâthe doctrine of signatures, and of harmony among the realms of nature. To unravel the archaeology of human knowledge, we must treat former systems of belief as valuable intellectual “fossils,” offering insight about the human past, and providing precious access to a wider range of human theorizing only partly realized today. If we dismiss such former systems as absurd because later discoveries superseded them, or as mystical in the light of causal systems revealed by these later discoveries, then we will never understand the antecedents of modern views with the same sympathy that Croll sought between weapon and wound, and Kircher proposed between human organs and healing plants.

[In this light, for example, the conventional image of Paracelsus himself as the ultimate mystic who sought to transmute base metals into gold, and to create human homunculi from chemical potions, must be reevaluated. I do not challenge the usual description of Paracelsus as, in the modern vernacular, “one weird dude”âa restless and driven man, subject to fits of rage and howling, to outrageous acts of defiance, and to drinking any local peasant under the table in late-night tavern sessions. But, as a physician, Paracelsus won fame (and substantial success) for his cautious procedures based on minimal treatment and tiny doses of potentially effective remedies (in happy contrast to the massive purging and bloodletting of Galenic doctors), and for a general approach to diseaseâas an incursion of foreign agents that might be expelled with healing substancesâthat provided generally more effective remedies than any rebalancing of humors could achieve. Even his chosen moniker of Paracelsusâhe was christened Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheimâmay not bear the arcane and mystical interpretation usually presented in modern accounts. Perhaps he did mean to highlight the boastful claim that he had advanced beyond

(para)

the great Roman physician Celsus. But I rather suspect, as do many other scholars, that Paracelsus may simply represent a Latinized version of his birth name, Hohenheim, or “high country”âfor

celsus

, in Latin, means

“towering” or “lofty.” Many medieval and Renaissance intellectuals converted their vernacular names to classical equivalentsâas did Georg Bauer (literally “George the farmer,” in German) who became the world's greatest sixteenth-century geologist as the more mellifluous and Latinized Georgius Agricola, with the same meaning; or Luther's leading supporter, Philip Schwartzerd (Mr. “Black Earth” in his native lingo), who adopted a Greek version of the same name as Melanchthon.]

However, while we should heed the scholar's plea for sympathetic study of older systems, we must also celebrate the increase and improvement, achieved by science, in our understanding of nature through time. We must also acknowledge that these ancient and superseded systems, however revealing and fascinating, did impede better resolutions (and practical cures of illness) by channeling thought and interpretation in unfruitful and incorrect directions.

I therefore searched through Schröder's

Pharmacopoeia

to learn how he treated the objects of my own expertiseâfossils of ancient organisms. The search for signatures to heal afflicted human parts yielded more potential remedies from the plant and animal kingdoms, but fossils from the mineral realm also played a significant role in the full list of medicines. Mineral remedies discussed by Schröder, and made of rocks in shapes and forms that suggested curative powers over human ailments, included, in terminology that prevailed among students of fossils until the late eighteenth century, the following items in alphabetical order:

1. A

ETITES

, or “pregnant stones” found in eagles' nests, and useful in a suggestive manner:

partum promovet

â“it aids (a woman in giving) birth.”

2. C

ERAUNIA

, or “thunder stones,” useful in stimulating the flow of milk or blood when rubbed on breasts or knees.

3. G

LOSSOPETRA

, or “tongue stones,” an antidote to poisons of animal wounds or bites.

4. H

AEMATITES

, or “bloodstones,” for stanching the flow of blood:

refrigerat, exiccat, adstringit, glutinat

â“it cools, it dries out, it contracts, and it coagulates.”

5. L

APIS

LYNCIS

, the “lynx stone” or belemnite, helpful in breaking kidney stones and perhaps against nightmares and bewitchings. Many scholars viewed these smooth cylindrical fossils as coagulated lynx urine, but Schröder dismisses this interpretation as an old fable, while supplying no clear alternative.