Hyperspace (11 page)

Authors: Michio Kaku,Robert O'Keefe

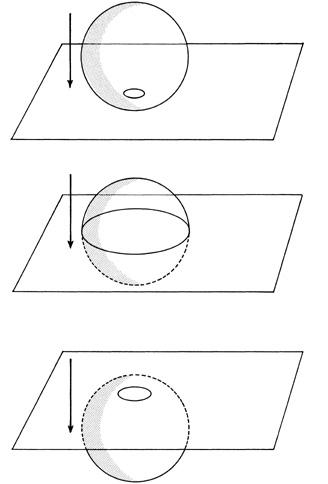

Discussion of the third dimension is strictly forbidden. Anyone mentioning it is sentenced to severe punishment. Mr. Square is a smug, self-righteous person who would never think of challenging the Establishment for its injustices. One day, however, his life is permanently turned upside down when he is visited by a mysterious Lord Sphere, a three-dimensional sphere. Lord Sphere appears to Mr. Square as a circle that can magically change size (

Figure 3.1

)

Lord Sphere patiently tries to explain that he comes from another world called Spaceland, where all objects have three dimensions. However, Mr. Square remains unconvinced; he stubbornly resists the idea that a third dimension can exist. Frustrated, Lord Sphere decides to resort to deeds, not mere words. He then peels Mr. Square off the two-dimensional Flatland and hurls him into Spaceland. It is a fantastic, almost mystical experience that changes Mr. Square’s life.

As the flat Mr. Square floats in the third dimension like a sheet of paper drifting in the wind, he can visualize only two-dimensional slices of Spaceland. Mr. Square, seeing only the cross sections of three-dimensional objects, views a fantastic world where objects change shape and even appear and disappear into thin air. However, when he tries to tell his fellow Flatlanders of the marvels he saw in his visit to the third dimension, the High Priests consider him a blabbering, seditious maniac. Mr. Square becomes a threat to the High Priests because he dares to challenge their authority and their sacred belief that only two dimensions can possibly exist.

Figure 3.1. In Flatland, Mr. Square encounters Lord Sphere. As Lord Sphere passes through Flatland, he appears to be a circle that becomes successivley larger and then smaller. Thus Flatlanders cannot visualize three-dimensional beings, but can understand their cross sections

.

The book ends on a pessimistic note. Although he is convinced that he did, indeed, visit the third-dimensional world of Spaceland, Mr. Square is sent to jail and condemned to spend the rest of his days in solitary confinement.

Abbot’s novel is important because it was the first widely read popularization of a visit to a higher-dimensional world. His description of Mr. Square’s psychedelic trip into Spaceland is mathematically correct. In popular accounts and the movies, interdimensional travel through hyperspace is often pictured with blinking lights and dark, swirling clouds. However, the mathematics of higher-dimensional travel is much more interesting than the imagination of fiction writers. To visualize what an interdimensional trip would look like, imagine peeling Mr. Square off Flatland and throwing him into the air. As he floats through our three-dimensional world, let’s say that he comes across a human being. What do we look like to Mr. Square?

Because his two-dimensional eyes can see only flat slices of our world, a human would look like a singularly ugly and frightening object. First, he might see two leather circles hovering in front of him (our shoes). As he drifts upward, these two circles change color and turn into cloth (our pants). Then these two circles coalesce into one circle (our waist) and split into three circles of cloth and change color again (our shirt and our arms). As he continues to float upward, these three circles of cloth merge into one smaller circle of flesh (our neck and head). Finally, this circle of flesh turns into a mass of hair, and then abruptly disappears as Mr. Square floats above our heads. To Mr. Square, these mysterious “humans” are a nightmarish, maddeningly confusing collection of constantly changing circles made of leather, cloth, flesh, and hair.

Similarly, if we were peeled off our three-dimensional universe and hurled into the fourth dimension, we would find that common sense becomes useless. As we drift through the fourth dimension, blobs appear from nowhere in front of our eyes. They constantly change in color, size, and composition, defying all the rules of logic of our three-dimensional world. And they disappear into thin air, to be replaced by other hovering blobs.

If we were invited to a dinner party in the fourth dimension, how would we tell the creatures apart? We would have to recognize them by

the differences in how these blobs change. Each person in higher dimensions would have his or her own characteristic sequences of changing blobs. Over a period of time, we would learn to tell these creatures apart by recognizing their distinctive patterns of changing blobs and colors. Attending dinner parties in hyperspace might be a trying experience.

The concept of the fourth dimension had so pervasively infected the intellectual climate by the late nineteenth century that even playwrights poked fun at it. In 1891, Oscar Wilde wrote a spoof on these ghost stories, “The Canterville Ghost,” which lampoons the exploits of a certain gullible “Psychical Society” (a thinly veiled reference to Crookes’s Society for Psychical Research). Wilde wrote of a long-suffering ghost who encounters the newly arrived American tenants of Canterville. Wilde wrote, “There was evidently no time to be lost, so hastily adopting the Fourth Dimension of Space as a means of escape, he [the ghost] vanished through the wainscoting and the house became quiet.”

A more serious contribution to the literature of the fourth dimension was the work of H. G. Wells. Although he is principally remembered for his works in science fiction, he was a dominant figure in the intellectual life of London society, noted for his literary criticism, reviews, and piercing wit. In his 1894 novel,

The Time Machine

, he combined several mathematical, philosophical, and political themes. He popularized a new idea in science—that the fourth dimension might also be viewed as time, not necessarily space:

*

Clearly … any real body must have extension in

four

directions: it must have Length, Breadth, Thickness, and—Duration. But through a natural infirmity of the flesh … we incline to overlook this fact. There are really four dimensions, three which we call the three lanes of Space, and a Fourth, Time. There is, however, a tendency to draw an unreal distinction between the former three dimensions and the latter, because it happens that our consciousness moves intermittently in one direction along the latter from the beginning to the end of our lives.

3

Like

Flatland

before it, what makes

The Time Machine

so enduring, even a century after its conception, is its sharp political and social critique. England in the year 802,701, Wells’s protagonist finds, is not the gleaming citadel of modern scientific marvels that the positivists foretold. Instead, the future England is a land where the class struggle went awry. The working class was cruelly forced to live underground, until the workers mutated into a new, brutish species of human, the Morlocks, while the ruling class, with its unbridled debauchery, deteriorated and evolved into the useless race of elflike creatures, the Eloi.

Wells, a prominent Fabian socialist, was using the fourth dimension to reveal the ultimate irony of the class struggle. The social contract between the poor and the rich had gone completely mad. The useless Eloi are fed and clothed by the hard-working Morlocks, but the workers get the final revenge: The Morlocks eat the Eloi. The fourth dimension, in other words, became a foil for a Marxist critique of modern society, but with a novel twist: The working class will not break the chains of the rich, as Marx predicted. They will eat the rich.

In a short story, “The Plattner Story,” Wells even toyed with the paradox of handedness. Gottfried Plattner, a science teacher, is performing an elaborate chemical experiment, but his experiment blows up and sends him into another universe. When he returns from the netherworld to the real world, he discovers that his body has been altered in a curious fashion: His heart is now on his right side, and he is now left handed. When they examine him, his doctors are stunned to find that Plattner’s entire body has been reversed, a biological impossibility in our three-dimensional world: “[T]he curious inversion of Plattner’s right and left sides is proof that he has moved out of our space into what is called the Fourth Dimension, and that he has returned again to our world.” However, Plattner resists the idea of a postmortem dissection after his death, thereby postponing “perhaps forever, the positive proof that his entire body had had its left and right sides transposed.”

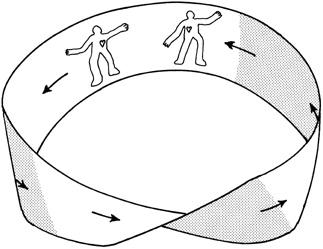

Wells was well aware that there are two ways to visualize how left-handed objects can be transformed into right-handed objects. A Flat-lander, for example, can be lifted out of his world, flipped over, and then placed back in Flatland, thereby reversing his organs. Or the Flat-lander may live on a Möbius strip, created by twisting a strip of paper 180 degrees and then gluing the ends together. If a Flatlander walks completely around the Möbius strip and returns, he finds that his organs have been reversed (

Figure 3.2

). Möbius strips have other remarkable properties that have fascinated scientists over the past century. For example, if you walk completely around the surface, you will find that it has only one side. Also, if you cut it in half along the center strip, it remains in one piece. This has given rise to the mathematicians’ limerick:

Figure 3.2. A Möbius strip is a strip with only one side. Its outside and inside are identical. If a Flatlander wanders around a Möbius strip, his internal organs will be reversed

.

A mathematician confided

That a Möbius band is one-sided

And you’ll get quite a laugh

If you cut it in half,

For it stays in one piece when divided.

In his classic

The Invisible Man

, Wells speculated that a man might even become invisible by some trick involving “a formula, a geometrical expression involving four dimensions.” Wells knew that a Flatlander disappears if he is peeled off his two-dimensional universe; similarly, a man could become invisible if he could somehow leap into the fourth dimension.

In the short story “The Remarkable Case of Davidson’s Eyes,” Wells explored the idea that a “kink in space” might enable an individual to

see across vast distances. Davidson, the hero of the story, one day finds he has the disturbing power of being able to see events transpiring on a distant South Sea island. This “kink in space” is a space warp whereby light from the South Seas goes through hyperspace and enters his eyes in England. Thus Wells used Riemann’s wormholes as a literary device in his fiction.

In

The Wonderful Visit

, Wells explored the possibility that heaven exists in a parallel world or dimension. The plot revolves around the predicament of an angel who accidentally falls from heaven and lands in an English country village.

The popularity of Wells’s work opened up a new genre of fiction. George McDonald, a friend of mathematician Lewis Carroll, also speculated about the possibility of heaven being located in the fourth dimension. In McDonald’s fantasy

Lilith

, written in 1895, the hero creates a dimensional window between our universe and other worlds by manipulating mirror reflections. And in the 1901 story

The Inheritors

by Joseph Conrad and Ford Madox Ford, a race of supermen from the fourth dimension enters into our world. Cruel and unfeeling, these supermen begin to take over the world.

The years 1890 to 1910 may be considered the Golden Years of the Fourth Dimension. It was a time during which the ideas originated by Gauss and Riemann permeated literary circles, the avant garde, and the thoughts of the general public, affecting trends in art, literature, and philosophy. The new branch of philosophy, called Theosophy, was deeply influenced by higher dimensions.

On the one hand, serious scientists regretted this development because the rigorous results of Riemann were now being dragged through tabloid headlines. On the other hand, the popularization of the fourth dimension had a positive side. Not only did it make the advances in mathematics available to the general public, but it also served as a metaphor that could enrich and cross-fertilize cultural currents.