How to Be Alone (School of Life) (7 page)

Read How to Be Alone (School of Life) Online

Authors: Sara Maitland

Tags: #Politics & Social Sciences, #Philosophy, #Self-Help, #Personal Transformation, #Self-Esteem

Perhaps it is better to approach this question anecdotally, through ‘case histories’. Because lives of solitude have been seen by so many different societies as both heroic and bizarre, there is a kind of fascination in solitary practitioners and therefore a fairly steady stream of biographical literature, across a prolonged historical period and from a range of cultures. It is not difficult to find a wide selection of individuals who practised a wide range of solitary lifestyles and simply look and see if there is any suggestion that being alone is dangerous rather than beneficial.

Anthony the Great

(AD

251–356) is widely credited as the first Christian hermit, and the founding father of monasticism. In 285 he went out into the Egyptian desert and lived in complete isolation in a ruined fort at Der el Memum (Pispir) for twenty years. Athanasius, his friend and biographer, describes his emergence from this long solitude in some detail. Anthony announced his intention of coming out and sent for some local workmen to help him dismantle his protective ‘fortifications’. This attracted a curious crowd who, Athanasius says, were all very ‘surprised’ to find he was neither emaciated nor deranged, suggesting clearly that this was the expectation. But he emerged physically fit and eminently in his right mind.

Despite these negative expectations, the rest of Anthony’s life seems remarkably sane; and he lived to an extreme old age (105, according to tradition, at a period when life expectancy was much lower than it now is), alone in the desert, still physically and mentally fully active, so his health was evidently not damaged. He spent the five or six years after he left Pispir sharing his experiences and training and organizing the new movement that had grown up around his fort. His success in both establishing a genuinely innovative spirituality and in creating structures that enabled the whole desert-hermit movement to develop over the following three centuries (and expand in an adapted form into Europe and become the basic impulse for monasteries) hardly suggests any serious damage.

After this teaching period he withdrew again into solitude, which he pursued with ‘joyful determination’ on his so-called ‘inner mountain’. This second period of solitude, which lasted for the remaining forty-five years of his life, lacked the extremity and rigour of his time in Pispir. He freely met and talked with those who came out to see him, sometimes walked back to visit his community in Pispir and, according to Athanasius, went twice to Alexandria. He was very much loved and respected, partly for his serene good humour and tranquil heart.

Oddly enough, the fact that he remained abundantly normal did not change the common terror that solitude was likely to drive people mad.

Anthony’s life pattern – a period of training, a period of extreme isolation, followed by teaching and public ministry and then a gentler withdrawal into seclusion – has been repeated ever since with surprising frequency and across a range of cultures. Tenzin Palmo is a contemporary example who has followed Anthony’s old road.

Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo is a British-born Tibetan Buddhist nun and probably one of the best-known solitaries of our time. She was born in 1943 in Hertfordshire, but moved to India when she was twenty and began training, the only woman in a community of over 100 male monks. She found this, not surprisingly, very difficult, as she felt she was often deprived of both higher teaching and respect because of her gender, and she gradually moved into a life of more solitude. From 1976 she lived for twelve years alone in a cave in the Himalayas, and for the last three of these in complete isolation. Even though her solitude was broken into in an abrupt and potentially damaging way (one day a policeman arrived saying she had twenty-four hours to appear in the nearest town as her visa had expired and she had to leave the country), she appeared unruffled and healthy.

She also emerged with a great determination to improve the position of Buddhist nuns. She spent the following years in Europe teaching, lecturing and raising funds for what, in 2000, became the Dongyu Gatsal Ling Nunnery in Himachal Pradesh, India. Again, like Anthony, after this period of teaching and organizing she is speaking again of ‘retreat’, of going back to her solitary lifestyle.

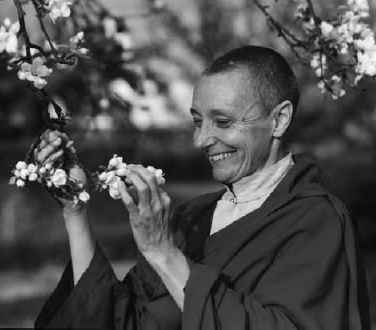

Like Anthony too she seems marked not just by sanity but by a benign and slightly ironic humour. She appears tolerant, witty and articulate and the many pictures of her show a woman in her seventies in good health and spirits. She is, apparently, an extraordinarily good public speaker and teacher, and continues to work, with considerable success, for the spiritual rights of Buddhist women.

Sadly, a number of individuals embracing a life of radical solitude have gone very mad indeed – like Marguerite de la Rocque, marooned for two years on an island in the St Lawrence Seaway in 1641, who was assaulted and haunted by demons, although she recovered on her return to France, or Alexander Selkirk, the probable model for Robinson Crusoe, who was never able to return to social life after his rescue, and lived in a cave in Scotland – but so have a number of people who have not spent any significant time alone. Overall I can find no evidence whatsoever that there is a higher incidence of lunacy, chronic ill health or early death among the solitary than in the population at large, though I admit that this would be extremely difficult to measure. Although there are intense experiences and sometimes frightening issues to work through, being alone can be beneficial and is certainly not detrimental to well-being,

provided the individuals have freely chosen it.

A good deal of the ‘scientific evidence’ for the danger to physical and mental health comes from studies of people in solitary confinement. There is no question that compulsory punitive isolation is extremely dangerous to the human psyche – and can lead to a particularly hideous form of psychosis. But to compare freely chosen adventures into the world’s wilder places, or the experience of the divine and the depth of the self, to the ordeal of prisoners is a bit like comparing the feelings of a woman pregnant with a wanted baby, basking in support and encouragement, to a woman similarly pregnant but as a consequence of rape, and facing shame and poverty. Of course no one should expect them to feel the same way.

Tenzin Palmo: Marked not just by sanity but by a benign and slightly ironic humour.

So the biggest danger of solitude is fear – and often fear mixed with both the derision and judgement of others. Those exploring solitude can reasonably anticipate accusations of madness, selfishness and stupidity; and since of course there are going to be elements of all three in all of us, these can sink their barbs in deep, depriving us of joy, confidence and faith; and into the space thus created madness, egotism and idiocy can sneakily enter. Fear is more likely to undermine health than being alone is.

2. Do Something Enjoyable Alone

The most commonly offered reason for not doing something like regular exercise is ‘I don’t have the time …’ Often this is a pretty transparent excuse (‘I don’t have time to go to the doctor, but I do have time to play computer games’). But in fact many of us do live extremely busy and pressured lives, and, particularly if we share a home with others, find it difficult to see where yet another clump of hours can be fitted into a life which feels, and perhaps is, already short of them.

This is a genuine difficulty in relation to solitude, because it is too easy to think of it as a ‘new’ sort of time, which will have to be carved out of other activities. Usually we cannot choose whether we are alone at work, so if we want to experiment with solitude it seems as though it will have to be in our ‘spare’ or leisure time. But as a society we have constructed leisure as predominantly a communal activity. People who indulge in solitary hobbies are treated as ‘odd’, if not contemptible: ‘geeks’, ‘nerds’, ‘anoraks’ – trainee ‘loners’, in all likelihood!

There are some popular leisure activities which cannot be enjoyed alone – team sports are an obvious example, as are Scottish reel dancing, board games and gossip. The activities that can only be enjoyed alone form a smaller but significant group – reading being perhaps the most obvious one. But there are a very large number that can be, and often are, done either in a group

or

alone, like listening to or making music, walking, gardening and watching TV.

It is interesting, occasionally, to look in detail at how one does actually spend one’s leisure time – within the working week, during non-working days like weekends and on holiday. Such a list, made honestly, usually shows us just how much time we waste doing nothing in particular at all – ‘neither what we want nor what we ought,’ as C. S. Lewis described it. But more importantly it reveals that most of us have a pretty clear division between ‘work’ and ‘leisure’. This distinction is a strong feature of post-industrial societies and simply did not exist before that. It is a common belief that so-called ‘advanced societies’ have more leisure than people used to have – but anthropologists now recognize that hunter-gatherer societies have the most leisure and that ‘downtime’ is one of the biggest losses of modernity. Even in mediaeval Europe the peasant had far more holidays than a middle-class salaried worker has now.

As well as reducing our leisure hours, modern societies have also massively increased the amount of ‘maintenance’ time we feel is essential for all that washing and cleaning and grooming and decorating – ourselves and our homes. This is partly because we have separated ‘work’ and ‘maintenance’: a great deal of necessary maintenance now takes double the time to perform, because first we have to work to earn the money that enables us to do the task. If you are living by subsistence agriculture you might barter to some extent, but you never need to go shopping. It is also partly because over the last couple of centuries we have raised and elaborated our ideas of

necessary

maintenance: far from providing more leisure time, labour-saving domestic devices have made a higher standard of cleanliness obligatory – a daily bath or shower, daily clean underwear, regular changes of bedding, frequent hair-washing and so on – unknown to even prosperous households a century ago.

Even in mediaeval Europe the peasant had far more holidays than a middle-class salaried worker has now.

But the real reason why maintenance takes more time is because we own so many more things, all of which need maintaining. We work longer hours to buy the things, and then we spend more hours managing and looking after them, and so as we become money-richer we also become leisure-poorer.

We are leisure-poor, then, because the combined burden of work and maintenance takes up so much of our time and because we have compartmentalized the three activities. Moreover, in addition to compartmentalizing them in time, we have also divided them in space – we use an increasing amount of our day to move between the locations where the three things take place. There are other ways to be.

I live on a high moor in southwest Scotland. Not much flourishes here except blackface ‘freerange’ sheep. Like many infertile upland areas it got left behind in the years after WWII. There was no electricity until 1972; the thirteen miles of unmetalled single-track road between one village and the next had thirteen gates which had to be opened and closed. Each farm was isolated from its neighbours – and most people worked alone. Every summer, though, they had Common Shearing: five or six farms would get together and shear all the sheep, farm by farm; the shearers sitting in a circle on shearing stools, chatting and singing as they worked. The whole family from each farm would come, and whosever farm the shearing was at that day fed everyone. All the older people in this glen remember Common Shearing as a social activity, even though hand shearing is hard work and an economic necessity. Electricity, as well as a sharply declining population, ended Common Shearing – power shears are too fast and also too noisy for sociability. Work and leisure are no longer seamless.

Life patterns like this have had a long-term influence on our ideas about ‘leisure’. When people worked alone, or with a tiny and unchanging group like the family, and leisure and work were more closely entwined than they now are – markets (work) were also fairs (leisure) – hours spent not alone were social occasions in predominantly solitary lives. So leisure became associated with group activities and with sociability. Most of our team and competitive sports evolved from local and traditional games; much of our preferred music (the orchestra, the group, the choir) likewise emerged from communal activity. Even the word ‘holiday’ is derived from the concept of Holy Days, when mediaeval peasants did not have to perform work duties but did have to go to church – a profoundly corporate event.