How to Be Alone (School of Life) (8 page)

Read How to Be Alone (School of Life) Online

Authors: Sara Maitland

Tags: #Politics & Social Sciences, #Philosophy, #Self-Help, #Personal Transformation, #Self-Esteem

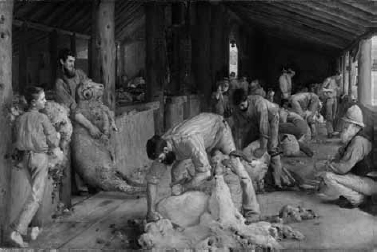

Common Shearing was a social activity, even though hand shearing was hard work and an economic necessity.

Now most of us do not work alone. We do not even work in the noisy, dangerous places that so isolated individual workers in nineteenth-century factories. But still when we think about ‘leisure’ in our time-stressed, noisy lives, we tend to think of social rather than solitary activities; and think there is simply no space, once we have built in work, maintenance and ‘leisure’, for time to be alone.

This is why it is worth rethinking the leisure you already enjoy and seeing if there are ways of increasing your time alone within that framework. This has the additional advantage of relieving some of the anxiety about solitude by associating it with an activity you already know you enjoy.

Running alone can allow you to hit the mute button on the world […] and take full advantage of exercise’s stress-busting benefits. ‘Running alone can be a meditative experience where you get to really think and concentrate or completely clear your mind and zone out,’ [psychotherapist Michelle] Maidenberg says. […] ‘You have to practise letting go of the inner chatter that can get in the way of what you want to accomplish,’ [sports psychologist Cindra Kamphoff says]. ‘And that’s something you have to do on your own.’

(

Runner’s World,

March 2013)

Jogging as a physical discipline was really only established in the 1960s. (The first use of the noun ‘jogger’ occurred in 1968, in New Zealand.) This may explain why it is one of the few leisure activities that it is normal to see people doing alone: it was a response to the symptoms of modernity I have been describing, and so free of the residual ‘leisure as social’ culture that preceded it. But in fact it is perfectly possible to do many other activities – outdoors and in – alone: go to the cinema, an art gallery or up a mountain; fishing, gardening.

Reading and listening to music (or even playing an instrument) are obvious leisure activities which people do alone; but they do present an odd question. When you read, are you alone? When you listen to music – particularly vocal music – is that a solitary activity? Or is it something you are doing in the company of the writer, the composer or the singers?

Sara, coming home.

And above all, walking. For me, solitary walking, especially but by no means exclusively in wilder places, feels like a necessity as well as a joy. Solitary walking is a profound image of independence and personal integrity. This makes it a good way to start exploring solitude; it is hard, when walking, not to feel good about yourself and about your capacity to be alone. In addition, it is available to almost everyone (you just walk a shorter distance if you are less fit), extremely cheap and embellished with happy associations with creativity, health and pleasure.

There is a good deal of anecdotal evidence that doing things alone intensifies the emotional experience; sharing an experience immediately appears to dissipate our emotional responses, as though communicating it drained away the visceral sensation. I walk a good deal alone and my own experience is that this is very different from walking – even the same walks – in company. I see and notice more and experience both the environment and my physical response to it in a very clear, direct way. I also like walking with other people and do that too. The freedom to walk alone, to eat alone, to travel alone gives at the very least a wider potential pleasure. I would feel deprived if both were not possible for me.

3. Explore Reverie

If you have the opportunity to watch a very young child who is comfortable and content and neither hungry nor stressed, you can often observe an almost mystical, indescribable expression: the baby’s eyes are fixed on some object – very often a loved face – but are also unfocused. The child can take on a Buddha-like appearance – completely intent and completely relaxed. Donald Winnicott believed that the capacity to be alone, to enjoy solitude in adult life, originates in these moments, with the child’s experience of being ‘alone in the presence of the mother’. (It does not need to be the biological mother who can offer the child this gift.) He postulates a moment in which the child’s immediate needs – for food, warmth, physical and emotional contact – have been satisfied, so that there is no need for the infant to be looking for anything; she is free just to be.

Winnicott is describing in psychoanalytical terms what the Psalm writer wrote nearly 4,000 years earlier in spiritual terms:

See, I have set my soul in silence and in peace;

As the weaned child on its mother’s breast, So even is my soul.

(Psalm 131:1–3)

Both Winnicott and the Psalmist are paying attention here to the experience of the child – but reflecting on my own life, I would say that at their very best these rich and lovely moments are entirely mutual. I think that the hours spent thus with my children, especially after the night feeds, were key experiences which encouraged me (literally – gave me the courage) to explore silence and solitude with hope and engagement.

Unfortunately the way most of us were brought up, with an immensely strong focus on stimulation, engagement and interaction, means that too many of us have become adults with no experience of and no capacity for solitude; not because we were neglected or frightened or emotionally isolated but simply because we got no safe practice in our infancy, always being joggled and sung to and dandled and put down and picked up and talked to and interacted with.

As we grew up this continued. Despite the simple fact that the number of abductions and murders of children by strangers has not increased since the 1950s (approximately fifty children are murdered each year in the UK; but over two-thirds of these are killed by a parent or principal carer, not by a stranger) and remains remarkably rare, the fear of it has increased exponentially. This is very odd. It means that even people who can recall how joyful and important time alone was to them as children do not hand this message on to the next generation, but instead wrap the whole idea of solitude in a blanket of anxiety and fear. This increases our nervousness about it, which makes us more reluctant to try it out and often more frightened than there is any need to be.

Luckily there is a ‘technique’ (if that is the right word) for making good some of this loss. In 1913 the psychoanalyst Carl Jung (1875–1961), having broken with his friend and mentor Freud and been cut off by the impending war from much of his erstwhile social circle, experienced a sort of breakdown, what he himself described as a horrible ‘confrontation with the unconscious’, including voice-hearing and hallucinations. He was terrified that he might be becoming psychotic, but bravely decided to confront his fears with a sort of self-analysis. In solitude he worked himself into a state of reverie – a kind of concentrated daydreaming which he called ‘active imagination’. He deliberately and as detachedly as possible worked through his own memories and dreams and his emotional reactions to them, and then recorded the sessions in notebooks.

He came to believe that this had proved extremely valuable, and in later clinical practice, especially with older clients, would help people learn to do this for themselves. Because of our contemporary emphasis on object relations (and conceivably because of professional and egocentred considerations) this ‘treatment’ has mainly dropped out of the mainstream (although you can get some basic practical advice online if you search for ‘self-analysis’).

Even without Jung’s alarming experiences,

reverie

is a useful way of setting boundaries and patterns to an initial exploration of solitude. One way of using this idea is to place yourself in comfort and safety and then actively seek significant memories of particular states of mind. One interesting feature that psychologists are uncovering is that when people seek moments of happiness, particularly elevated, unitive moments – when the daydreamer uses the active imagination to remember feeling joyfully bound to the whole earth or even universe – they are most likely to be associated with being alone, and often alone outside. Anthony Storr, in

Solitude,

associates this free-roaming solitary pursuit as a particular feature of highly creative people, especially writers. But I myself suspect that it is writers who are best at recording these moments, and that anyone who has had the opportunity to be alone for even relatively brief periods of time as a child can find and reexperience this intense pleasure.

Too often such delights get overlaid by the more social demands of young adulthood, by our own fears of isolation and of being thought weird, and by the culturally inculcated terror of solitude. Reverie is both highly pleasurable in itself and is also a fairly safe way of re-accessing memories.

Most such acts of recall come with a startling vividness – this is one of the ways that people authenticate their own memories. ‘It must be true because it feels so complete and satisfying; it must be true because it feels true.’ In fact, we now know that memories of childhood are extremely unreliable and are to a large extent confabulations; they are creative acts, constantly in flux and transformation. To me this makes the amazing frequency with which people remember childhood moments of solitude in a positive and often romantic glow all the more interesting. It seems to suggest that as adults many of us have a deep and real longing for more solitude than we are presently getting.

Such practices can, incidentally, throw up quite disturbing material. If this all becomes consistently more frightening than either pleasurable or interesting, it is worth checking whether you are actually exhaling enough (hyperventilation is easy to slip into and produces weird physical effects), and otherwise give yourself a break. I am not proposing this as necessary therapy, but as a rather effective way to enjoy solitude more. If it does not work, does not achieve this end for you, do something different.

4. Look at Nature

By ‘look at nature’ I do not mean ‘get out into nature’ – although, as I have already suggested, this is a very good thing to do when you are alone. As I have described, one of the arguments deployed against those who want to be alone is that such a desire is ‘unnatural’.

This is a complicated sort of accusation, made up of so many strands that it is quite difficult to unravel and examine it, and indeed it has built itself so deeply into our culture and ways of thought that we seldom even try to unravel and examine it. The word ‘natural’ has aggregated a confusingly wide range of meanings, some of which are in contradiction to each other. For example, the

Oxford English Dictionary,

along with sixteen other separate meanings for ‘natural’ as an adjective, defines it both as something ‘based upon the innate

moral

feeling of mankind; instinctively felt to be right and fair’ and as something ‘in a state of primitive development, not spiritually enlightened. Unenlightened, unregenerate.’

Interestingly, until very recently one thing that ‘natural’ did not mean was ‘things like animals, trees, mountains and oceans’, although this is often the implication when people call something ‘unnatural’. We need to be alert to the implicit and conflicted moral judgement in the word itself because very often when people say something is ‘unnatural’, they really mean ‘I do not approve of it’.

Nonetheless the idea that it is unnatural for human beings to be solitary is very ancient, and still exercises imaginative hold on many of us. When the Pentateuch – the first five books of Scripture which are held in common by the three Middle Eastern monotheisms (Judaism, Christianity and Islam) – was given its final form, somewhere between 600 and 400

BC,

the second version of the Creation story (Genesis 2) tells how the Lord God made Adam, breathed life into him and put him in the Garden of Eden alone (there were not even any animals at this point) but then came to the conclusion that ‘it is not good that the man should be alone’. In an attempt to provide Adam with a fitting companion, the Lord God then ‘formed every beast of the field and every bird of the air and brought them to the man’. However, none of them seemed quite satisfactory, so the Lord God made a woman out of one of Adam’s ribs. And he was no longer alone. Quite why this one verse of Genesis has kept its resonance while the rest of the creation story has been militantly rejected is a bit mysterious.