How to Be Alone (School of Life) (14 page)

Read How to Be Alone (School of Life) Online

Authors: Sara Maitland

Tags: #Politics & Social Sciences, #Philosophy, #Self-Help, #Personal Transformation, #Self-Esteem

Perhaps the most famous book about being alone is by Henry Thoreau. Thoreau (1817–1862) was a nineteenth-century American author, poet, philosopher, abolitionist, naturalist, tax-resister, surveyor, historian and leading transcendentalist. In 1856 he published

Walden,

which is an account of the two years he spent living alone in a hut in a wood near Concord in Massachusetts. It has become a major classic, and together with Wordsworth’s ‘The Prelude’ – and much easier to read – it is the great book linking solitude and nature.

Isabel Colegate has written a lovely history of hermits called

A Pelican in the Wilderness

(HarperCollins, 2002). She defines ‘hermits’ in non-religious terms, but most of her subjects take a fairly extreme path of solitude. Peter France’s

Hermits: insights of solitude

(Chatto & Windus, 1996) is more focused on prayer and spirituality, but is beautifully written and illuminating about what people have gained from being alone through the centuries.

Richard Byrd (1888–1957) was a US admiral, early aviation adventurer and explorer. His book

Alone

(Shearwater Books, 2003; originally published 1938) describes his time alone in Antarctica. This expedition was not altogether successful: a faulty stove leaked carbon monoxide into his hut and he became seriously ill. The attempts to rescue him take up a good deal of the book. However, before he got sick he wrote some of the most beautiful prose about the beauty and solitude he found there. It is an inspiring read.

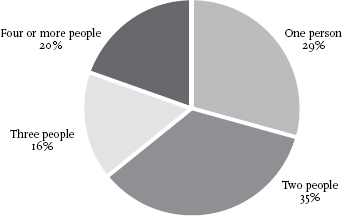

The figures from the 2011 Census for the UK have now been published by the Office of National Statistics in various forms, both online and print. They make a fascinating background to many discussions, including those contained in this book. Here is a pie chart showing the numerical size of households:

Notice how large the segment of single-person households is. It is not odd to live alone. Pin this graph up somewhere visible and if you find the idea of ‘being alone’ alarming, look at it and take comfort from the knowledge that you will not be alone in being alone!

Quakers (more formally called the Society of Friends) are a religious denomination founded in the seventeenth century. They are famous for their commitment to pacifism, their refusal to take oaths, their radical stand on a wide variety of issues, their complete lack of a leadership structure and their ‘meetings for worship’, which are predominantly silent. There will be a Quaker Meeting near you, and if you are uncertain whether it is silence or solitude you are most in search of, you might well find some clues by attending one. You will be made welcome and not pressured to ‘join’.

Trappists are an order of Roman Catholic monks who live under a ‘reformed’ version of the Rule of St Benedict, which incorporates a great deal of silence. The monks communicate in a form of simplified sign language. Thomas Merton (1915–1968) was a Trappist and

The Seven Storey Mountain

(published in the UK as

Elected Silence,

Hollis & Carter, 1949) describes the life of the monks. There are no Trappist monasteries in the UK, but there are various contemplative (more or less silent) orders, especially of women, and it is possible to visit many of them. Making a private visit, often called a ‘retreat’, is a very safe and structured way to experience being on your own, although surrounded by experts and well looked after. Most such communities welcome visitors; you do not have to be a Christian and will not be required to attend services. There is a comprehensive list of retreats available at www.retreats.org.uk.

My own

A Book of Silence

is published by Granta. Although, as I say, it is more about silence than about solitude per se, it is more or less impossible to write about one without writing about the other and it contains very full references to a great many books and individuals who have practised the two together.

II. Being Alone in the Twenty-first Century

1. Sad, Mad and Bad

James Friel is a novelist. His most recent book,

The Posthumous Affair,

was published by Tupelo Press in 2012. He teaches creative writing at Liverpool John Moores University. He lives alone.

In the third and fourth centuries thousands of Christians went off to be hermits in the desert – mainly in the Egyptian desert, but also in Sinai, in what is now Syria and in Jordan. It was perhaps the first large-scale experiment in being alone that we have any record of. These hermits are often called the Desert Fathers, although some of them were women. They were quite experimental – trying out a variety of forms of prayer, ways of supporting themselves, ascetic disciplines and lifestyles. They had enormous influence on subsequent Christianity, because monasticism, as it developed in the West, was based on their practices. As they were much admired by their contemporaries, their stories and reflections were collected in several different books. Anyone worried about solitude and sanity should read some of these ‘sayings’, as they are called. The most admired of these hermits tend to be gentle, generous, humble, kind and slightly self-mocking. There are many translations of these originals. I particularly like the tone of Helen Waddell’s 1936

The Desert Fathers

(Constable).

There are a number of biographies of Greta Garbo, perhaps the most famous ‘loner’ in modern history. The most recent is by David Bret –

Greta Garbo: Divine Star

(Robson Press, 2012).

2. How We Got Here

For the detailed history of the later period of Rome there is the famous (and enormous)

The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

by Edward Gibbon (published in six volumes between 1776 and 1781). He was perhaps the first serious historian to blame the fall of Rome on Christianity, which he thought made Romans ‘effeminate’.

A more contemporary approach to the specific issues I have been looking at can be found in the works of Professor Peter Brown (of Princeton), who has specialized in the religious culture of the later Roman Empire and early mediaeval Europe. He writes in a way that is wonderfully accessible as well as scholarly. Among his relevant books are:

Augustine of Hippo: A Biography

(University of California Press, 1967);

The Body and Society: Men, Women, and Sexual Renunciation in Early Christianity

(Columbia University Press, 1988) and most recently

Through the Eye of a Needle: Wealth, the Fall of Rome, and the Making of Christianity in the West, 350–550 AD

(Princeton University Press, 2012).

The Eagle of the Ninth Chronicles

(OUP, 2010) is a trilogy of children’s novels by Rosemary Sutcliff, set in Roman Britain. The third of the series –

The Lantern Bearers

– is an extremely moving account of the resistance to the Saxon invaders after Rome pulled the legions out of Britain to defend the imperial city itself. It addresses the conflict of values and the sense of devastation and cultural unhinging – on all sides – as the Empire declined and broke up.

In Britain at least thirty-six of our present towns and cities, including London, have Roman foundations. Visits to the Roman Baths in Bath (hence the city’s name) and the Amphitheatre in Chester both offer a powerful impression of the high value of public and civic life even at the furthest ends of the Empire. A trip that takes in both Hadrian’s Wall (and its associated artefacts) and Lindisfarne (the Holy Island) or the Farne Isles, where St Cuthbert (c. 634–687) had his hermitage, shows the contrast between the two ideals very sharply (while also providing some beautiful empty terrain for solitary walking).

The Romantic movement in Britain is best known through its poets: William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley and John Keats are perhaps the key names. Wordsworth was the most articulate about the value of solitude and its crucial importance to artists. It is a central and continuing theme of his work. For him solitude in nature was essential to creative inspiration. He has had immeasurable influence on the poetic ideal ever since. His poetry is still widely read and accessible. He is especially associated with the Lake District (Cumbria).

III. Rebalancing Attitudes to Solitude

Professor Robin Dunbar has written about his discoveries in numerous academic papers. But he has also written a general readers’ book called

How Many Friends Does One Person Need?: Dunbar’s Number and Other Evolutionary Quirks

(Faber & Faber, 2010). Although his work is really about human sociability rather than being alone, it is illuminating and thought-provoking about contemporary social culture. It is fun to read too, as he has a humorous and lively style.

Anne Wareham is a garden writer, and the author of

The Bad Tempered Gardener

(Francis Lincoln, 2011). Her garden at Veddw House in Monmouthshire (

www.veddw.com

) is one of my favourite in the country – beautiful, original and provocative. It is open to the public.

Catherine of Siena (1347–1380) was a rather extraordinary woman; despite a humble background she became a spiritual mentor to the then Pope and an influential figure in the complicated church politics of her time. She also had intense mystical experiences. Although illiterate, she is one of only four women ‘Doctors of the Church’ – a title conveyed on saints who have had a profound influence on theology. There are a number of biographies; in the context of understanding her ideas about solitude,

Catherine of Siena

by the Nobel Prize-winning novelist Sigrid Undset (Ignatius Press, 2009 – new edition) is excellent.

1. Face the Fear

Mind, the mental-health charity, has a good, practical down-to-earth pamphlet on phobias. If you do find being alone particularly disturbing or anxiety-provoking, or find other people’s enjoyment of being alone distasteful or repellent, it is worth reading this and exploring for yourself if your fears are actually a little pathological (

www.mind.org.uk/mental_health_a-z/8005_phobias

).

To be honest, I personally do not enjoy floatation tanks very much (mainly because I seem to roll over and get a mouthful of vile salinated water; but also because I best like my solitude in my house or outside in nature). But I know lots of people who love them. They are available at many beauty and health spas and are a good way of experimenting with being alone in a protected environment.

St Anthony the Great (251–356) is generally regarded as the founder of the Christian hermit tradition. He was an Egyptian Christian who went out to live in the desert. He attracted many followers. Athanasius (296–373), the Bishop of Alexandria, knew him personally and wrote his biography,

The Life of St Anthony,

which describes the early adventures in desert solitude with sympathy and admiration. It is still in print in numerous translations and editions.

Vicki Mackenzie has written a biography of Tenzin Palmo, paying special attention to her long periods of solitude –

Cave in the Snow

(Bloomsbury, 1999). In it she discusses the value and meaning of solitude in a Buddhist context. Palmo herself has commented that she does not know how Mackenzie managed to make a pageturner out of years of sitting in a small cave alone.

2. Do Something Enjoyable Alone

In addition to looking at how you spend your leisure time, it is also interesting to look at your own ‘maintenance’ time. This is partly because household maintenance is something that not only can be, but often is, done alone. If you are trying to find time for solitude, you may already have it if you stop seeing vacuuming as a disagreeable task and see it instead as a period of peaceful solitude; since it has a clear purpose and a definite point of completion, it may even turn out to be a very easy and unscary way of being alone.

3. Explore Reverie

Carl Jung’s own book

The Undiscovered Self,

which he wrote to try and explain his ideas to a non-specialist readership, puts my very inadequate description of his notion of ‘the active imagination’ into a wider theoretical context. Routledge published a new edition in 2002. Anthony Stevens’s

Jung: a very short introduction

(Oxford University Press, 2001) is also helpful.

Many people find ‘free writing’ is a helpful way of accessing this sort of material. Free writing is a technique originally developed to help with ‘writer’s block’ and is advocated by many creative writing guides like Julia Cameron’s

The Artist’s Way

(Pan, 1992) and Natalie Goldberg’s

Writing Down the Bones

(Shambhala Publications, 1986). The basic idea is that you set yourself a time limit (say fifteen minutes or half an hour) and you write, without stopping, whatever comes into your mind. You do not read it until afterwards and you do not correct it. For people who find more traditional reverie difficult or ‘pointless’, the act of writing seems to provide a focus.

4. Look at Nature

There are so many books about nature – and about specific species – that it is hard to make recommendations. When I really need to remind myself that there is no limit to the bizarre activities that are ‘natural’, I refer to

The Encyclopedia of Land Invertebrate Behaviour

by Rod and Ken Preston-Mafham (Blandford, 1993), which has beautiful photographs and describes an infinite variety of ‘natural’ adaptations which allow me to stop worrying about the odd social actions of my acquaintances.