Hold Still (14 page)

Authors: Nina Lacour

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Social Issues, #Friendship, #Suicide, #Depression & Mental Illness

“Hey,” she says to someone on the other end. “Yeah, I’m just leaving now.” She slams her locker shut and walks out, still talking.

And I think how perfect this is, that the one time I actually speak up for myself, the one time I actually know what to say, it’s over a nonexistent friendship.

I walk the back way home, fast, go straight to my room, unzip my backpack, and start reading. I need her.

By the time I’m finished reading I’m shaking. Everything gets blurry. I bury my head in my pillow, grab my comforter in both hands and try to rip it but nothing happens. I think about where she is now, in a coffin, underground in a cemetery I’ve only been to once and will never go to again. How it’s so easy for her to not feel anything at all, to be just completely gone, to not be around to see how fucked up she’s made me. She got to disappear completely and I feel like I’m about to combust. I stuff the corner of the blanket into my mouth until I can’t fit any more of it in and then I scream and scream and the sound comes out muffled. And I wonder what was so bad that she couldn’t do anything about it. What was so terrible that she felt she could never get over. When it gets too hard to breathe, I pull the blanket out and see that my teeth have only made little marks, tiny, invisible frays in the cotton. I can barely see them at all.

10

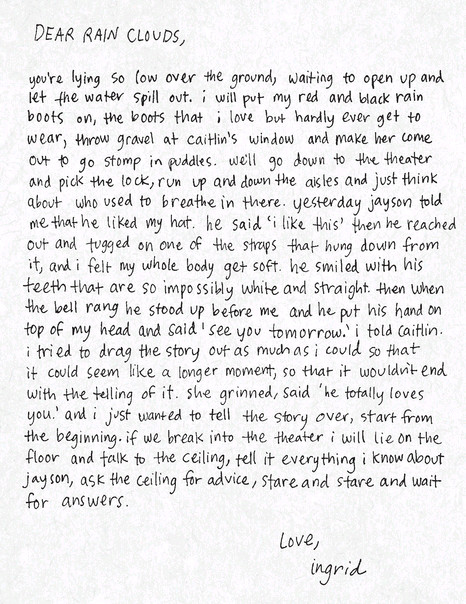

It’s already getting dark when I wake up later that night, Ingrid’s journal still open to the last entry I read. I can hear my parents downstairs making dinner. I have to clean my room—Taylor’s coming over soon—but I’m hungry.

“Well, hey there, Sleeping Beauty,” my dad says as I walk into the kitchen.

“Hey,” I mumble.

My mom comes up to give me a hug, but I lean over to peer into the pantry and she goes back to the stove. I know it’s mean of me, but I have this feeling that if I let her touch me, I would shatter into pieces.

“How was school?” my dad asks.

“Fine,” I say.

I rummage through all the weird snacks my parents eat: dried apples, instant oatmeal, wheat crackers.

“Well,” my dad says. “My day was fine, too. Thanks for asking. And let’s hear how your mother’s day was. Margaret?”

“It was nice, sweetheart,” she says to my dad, but like she’s really answering him, not trying to give me a lesson in social etiquette.

I find a bag of pretzels and tear it open, put one in my mouth, and taste the salt. My mom glances over at me. “Honey, have you been crying?” she asks.

I stare at the food she’s making and shrug.

“Taylor’s coming over to work on our project for precalc,” I say. “So I’m not going to be able to eat with you guys.”

“Can’t he come over after dinner?” my dad asks.

“This is important,” I say. “You know it’s, like, for school?”

“Well, he’s welcome to join us.”

“Uh, no thanks.”

“Why were you crying?” my mom asks. “Are you okay?”

“I just had a bad day. Is that not allowed?” I say, and it comes out a little harsher than I meant it to. I turn away and start heading back up to my room with the pretzels. On my way out I grab a Popsicle from the freezer.

At eight-fifteen, the doorbell rings and I rush past my parents to let Taylor in. He looks around nervously and catches sight of my parents. They are sitting at the dining table, eating something that smells really good.

“I’m sorry to interrupt your dinner,” he says to them.

He’s carrying his backpack and his skateboard, but it’s clear that he’s tried to make himself look nice. He smells like shampoo.

“We’re having penne and a beet salad,” Mom says. “May we offer you some?”

“Thanks, but I already ate,” Taylor says, taking off his jacket.

“We can go upstairs now,” I say.

“Okay, great. I brought the map and those little pushpin things.”

We start to walk away when my dad calls out, “That’s a nice shirt you have on, Taylor.”

It’s just a plain T-shirt, solid green.

Taylor’s whole face turns red. “Um, thank you,” he stammers. He pauses, then adds, “Sir.”

Once my door is closed, he says, “Oh my God. Your dad totally hates me. He thinks I’m trouble. I knew I should never have bought that stupid sex shirt. I knew it was a stupid thing to do.”

“You should get a new one,” I say. “One that says something like ‘Will work for forgiveness.’ ”

“Or ‘redemption.’ ”

“Or ‘approval.’ ”

He smiles. “Think it would work?” he asks.

“Maybe.”

“Should I make the effort?”

He’s standing close to me; his breath smells minty, I can’t concentrate, so I say, again, “Maybe.”

We both stand there, not knowing what to say or do next, until Taylor sets his backpack down and starts taking stuff out. I sit down on the chair by my desk. I get up and sit on my bed. I get up again, and plant myself, cross-legged, on the carpet.

Taylor has already taken out everything we need to get started, but he doesn’t stop there. Soon pencils and paper napkins and paper clips and books for other classes form a small mountain beside him.

“Looking for something?” I ask.

“What? Oh. No, just taking inventory.” He dumps it all back in. Once everything is packed up again, he looks at all the stuff on my walls.

“Nice room,” he says.

And then, a second later, he says, “Oh.” It comes out kind of shocked, like it wasn’t something he meant to say. I look at him, then up to where he’s looking. It’s a picture of Ingrid tacked up on my wall. She looks pretty, standing on the grass by the reservoir smiling.

“You must miss her a lot.”

I can’t say anything. I pick at the carpet.

“If you don’t want to talk about it, it’s okay.”

I keep picking at the carpet, hoping that I won’t start crying again.

Taylor slides a rubber band off the map he brought and spreads the map out across the space between us.

“Okay,” he says. “So this is Nice, where Jacques DeSoir grew up. We should put the first thumbtack here. Where was the next place he went? I’ll look it up.”

He opens the book and flips through the pages. I don’t want to talk about geography; I just want to be close to someone. I know that I’m only a couple feet away from him. I know that my parents are only a staircase away.

But still, I feel alone.

Silently, I pull my shirt over my head.

My heart is beating in my throat.

Still staring at the book, he says, “Okay, so it looks like he went to these Greek Islands.” No boy has seen me in just a bra before. I wait for him to look up.

Then he does.

His face flushes and he swallows slowly. I ease forward, across a thousand pastel-colored countries and into his lap, wrap my legs around his waist, and kiss him.

His mouth feels cold and my tongue grazes his mint gum. He touches my back with warm hands and I wonder if he’s fantasized about something like this, if he’s ever thought of me like this before. I hope he has, because I’m not really this brave. We kiss and kiss. I wait for him to start fumbling with my bra strap like boys in movies do, but he doesn’t. His hands move across my back gently and I still feel far away. I still feel alone. I start hearing these words in my head.

i want you to touch me. i want you to take my clothes off.

I hear them over and over, like the chorus of a song, before I realize that they’re Ingrid’s words, that I’m feeling what Ingrid felt, and it’s then I start to panic. I don’t stop kissing Taylor. I don’t stop anything. I don’t know what I’ll do when this moment is over and I’ll actually have to see him look at me.

But then it happens.

Taylor’s body gets tense. He stops kissing me. I climb off of him. I sit. I cover my chest with my arm. I look at his sneakers, at the frays on the bottom of his jeans, anywhere but at his face. I look at his hand as it moves to where my tank top lies on the carpet and as he lifts it up for me to take. I put it back on.

We sit in silence.

Then Taylor says, “I should go.”

I close my eyes. I’m waiting for the world to end.

I nod, whisper, “Okay.”

There’s the sound of him putting his books back into his backpack, of him rolling up the map. The sound of a zipper zipping. The sound of him standing up. The silence of his not moving.

“I’ll see you tomorrow,” he says.

I open my eyes and scan the ceiling. “Okay.”

He walks softly out of my room. I watch the back of him as he eases the door closed. Once it’s shut, I lean forward and put my head in my hands. Then the door swings open again, and Taylor comes back. He leans against my wall and says, “Just so you know, I do like you. That just felt weird.”

I guess I should say something, but I don’t. At this moment I am so far from thinking clearly, so far from making sense.

“Caitlin?” he asks.

I look into his face for the first time in minutes.

“I just want to make sure you know. It’s not like I didn’t want it or anything.”

He waits for me to say something. When I don’t, he walks in from the doorway and kneels on the carpet next to me. I get this terrible feeling that he’s going to kiss my cheek out of pity. I put my hand over my face so he can’t get to it.

“You know,” he says, “I had this huge crush on you in third grade.”

“Third grade?” I don’t even remember knowing him in third grade.

“Yeah, Mrs. Capelli’s class. Remember?”

I move my hand away from my face. I do remember. Mrs. Capelli wore colorful sweaters that smelled like mothballs and kept a hamster as the class pet.

“Your desk was one row ahead of mine and one row over, which was like the best setup imaginable because I could stare at you all day long without you seeing me.”

I glance at him and try to remember what he looked like as a little kid. I can remember him from middle school, practicing skating tricks in the front circle after the bell rang, but I can’t visualize him as an eight-year-old.

I open my mouth to ask him a question, then think better of it.

“What?” he asks.

So I say it anyway. “What did you like about me?”

“Lots of things.” He shifts his weight and ends up a little closer to me—still not touching, but closer. “But what I remember the most is this thing you used to do whenever we did art projects.”

“What was it?”

“Okay, well, you know how we had those boxes at our desks with our names on them? You kept a plastic bag in one—not a grocery bag, it was more like a sandwich bag. So, I’d glance over at you a lot during art projects and watch you gluing things. You always worked really slowly and carefully, and you hardly ever finished anything.”

I nod. It’s true—the art hour was always too short.

“So when Mrs. Capelli would tell us that our time was up, most of the kids just dumped the colored-paper scraps and glitter and cotton balls and stuff into the trash, but you would get out your plastic bag and put everything you didn’t use inside it.”

I haven’t thought about that for years, but as he says it, I remember. I can see myself, my little-kid fingers putting everything into that bag, saving it for later.

“Popsicle sticks and those pipe-cleaner things . . . I mean, it was

junk,

but you’d put it in your bag with glitter and suddenly it would look special. It used to drive me crazy.”

He grins, and even though my heart is lodged permanently in my throat, I smile back.

“I mean crazy in a good way,” he adds. He stands up. “Okay, I’m really going now. See you tomorrow.”

Once I hear him descend the stairs and shut the front door, I get up and look in my closet for my third-grade yearbook. It only takes a minute to find. I stick it in my backpack.

“I’ll be outside,” I yell, so my parents won’t panic if they can’t find me later.

In the garage, I find my dad’s huge flashlight that he uses on his search-and-rescue trips. I turn it on and head down the hill, out to my oak tree. So far, I’ve built a ladder ten feet up and secured six spokes to the trunk, one for each wall of the treehouse. I balance the flashlight on a branch above my head, stuff some bolts in my pocket, grab my hammer, and haul up a plank of wood. Once I’m up, I straddle a branch and prop one end of the plank onto a step, and attach the other end to the end of a spoke so that they form a forty-five-degree angle. This new plank will be the first brace, and I need to attach six of them to support the six spokes. I keep my mind clear, focus on the sound of my hammer and the weight of the planks.

Once I’ve secured half of them, my arms feel weak. I’m determined to get all six up tonight, though, so I’ll just give myself a short break.

I ease my way to the ladder and climb down. I take the yearbook out of my backpack. The flashlight casts a glow all around me—on the tree trunk, the grass, the leaves on the ground, the twigs and the pebbles. If I could, I would collect everything about right now. It’s not that I’m happy. I’m embarrassed and confused and so mad at myself about Dylan. But there’s something about right now that feels good despite everything. Each time a breeze starts, I feel the air all the way through me.

I flip through the yearbook pages until I find Mrs. Capelli’s class. There, in the lower right corner, is Taylor’s picture—small, black-and-white, grainy, but still incredibly charming. He’s smiling this bright, open smile. Even then he looked like a kid from a movie, the kind who only has a couple lines and can’t even remotely act, but no one cares because he’s so cute. I find my own picture. I’m smiling shyly with my hair in barrettes, my face slightly tilted to one side. This was me before I knew about anything hard, when my whole life was packed lunches and art projects and spelling quizzes. When my biggest responsibility was the one weekend of the year when it was my turn to bring the class hamster to my house and make sure it had food and water.