Hold Still (9 page)

Authors: Nina Lacour

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Social Issues, #Friendship, #Suicide, #Depression & Mental Illness

I look up from the rug to her face. She’s smiling in the nicest way.

“What I would like,” I say, “is to go back to class.”

26

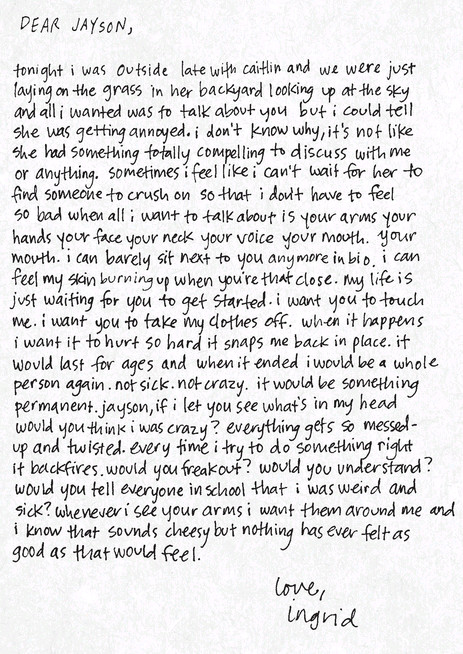

I leave school directly from the office and walk to my house the back way so no one will catch me. When I get home, I shut the door to my room even though no one else is there, just because it feels good to be alone, surrounded by my tacked-up band posters and magazine clippings. I unzip Ingrid’s journal from its pocket and sit down on the chair in the corner by the window. I open to the next entry, hoping Ingrid won’t be drooling all over Ms. Delani again.

I propel myself out of the chair and into my closet, holding Ingrid’s journal gingerly, like it’s too hot to touch. I pull all my clothes out of my hamper, drop the journal to the bottom, and stuff the clothes back on top.

It wasn’t unfair to not want to talk about Jayson every single minute. I mean, I always went along with plans she made to try to bump into him and to casually walk by his house after school sometimes, hoping he’d see us. Just because I wanted to talk about something different for a few minutes a day doesn’t mean that she had to write that about me. And that whole hurting thing? Ingrid and I felt the same about almost everything, so I don’t really understand. Maybe I misunderstood it. Whatever, it doesn’t matter. I don’t want to think about it anymore.

I go outside. I walk past my parents’ garden, where their parsnips are beginning to sprout, to the heap of wood. I pull a long plank off the pile and start to drag it away, down the slope of our backyard. It’s heavier than I thought it would be. I pull the plank past the brick patio, past the flowers, up and over this little hill, to the part where the land stops looking like a backyard and more just like a grassy area with a bunch of trees, almost dense enough to be a forest. I drop the wood at the base of the tree I like best. It’s a big oak. I used to climb it when I was a kid. After I catch my breath, I start back toward the house to get more. If I ever figure out something to build, I’m not going to do it with everyone watching.

Later, my parents call me down to the kitchen. I find Mom washing lettuce and Dad heating olive oil and garlic in a pan.

“What?” I ask them.

Dad turns to me. “Well, hello to you, too,” he says.

He’s taken his tie off and unbuttoned the first two buttons of his dress shirt. He holds his arm out to hug me, but I pretend I don’t notice and open the freezer instead. The cold feels good.

“How was your day, sweetheart?” my mom asks.

“Okay. Do you want help?”

“You could chop that onion,” she says.

I grab a knife from the drawer.

My dad continues some story he must have started to tell my mom before I came down. At first I try to listen, but I have no idea who he’s talking about. I cut the onion in half and my eyes burn.

A minute later, the phone rings and my dad hits the speaker button.

“Hello?”

We wait. A recorded voice comes on.

“This is the Vista High School office of attendance calling to report that your child missed one or more periods today. The absence will be marked as unexcused unless we receive a doctor’s note or notification from a parent or guardian explaining that the absence was due to a family emergency.”

My dad stops stirring. My mom turns the water off. I stand with my back to the phone, chopping.

Shit. I forgot about the phone calls.

“Caitlin, did you cut school?” Mom’s voice is straining to be patient.

I stop chopping and turn around, thinking maybe they’ll feel bad when they see what their onion is doing to my eyes. But they just stare at me.

I can’t think of a good excuse, so I just tell them, “I hate my photo teacher.”

“Ms. Delani?” Mom’s eyebrows lift in surprise.

“You liked her last year,” Dad says. My parents glance at each other, but they don’t say anything. I can see my mom get frustrated. Her lips are tight and she starts taking all these short breaths. Dad sighs.

Finally, he says, “Caitlin, you can’t ditch school. There are going to be a lot of people in your life who you won’t like and you’re going to have to learn to deal with them.”

“Ms. Delani is a very,

very

nice woman,” my mom says. “She taught you and Ingrid so much last year.”

“She didn’t teach me anything,” I say. “I wish I’d never met her.”

I turn to look out the window but it’s dark, so all I see is us, reflected. The most unlikely of family portraits. My mother, an apron tied over her suit, her hair falling out of a barrette; my father, leaning against the oven, one hand rubbing his forehead in exasperation; and me, staring straight at the lens, onion tears drying on my face. I try to think of some way to explain this situation to them, but my mom is going on and on about the dangers and consequences of skipping school until it seems so absurd that she’s reacting like this over something so small.

“Why are you laughing?” Mom asks me, her voice hurt and angry.

“I can’t help it,” I say, giggling now. “You’re acting psychotic.”

She stops talking. She stares at me hard, then wipes her hands on her apron. Calmly, she walks to the stove and turns it off. She turns toward me and I brace myself for a hug. But she brushes past me, lifts the cutting board from the counter, and scrapes the chopped onion in the trash can.

“I’ll be in our room,” she says to my dad, and leaves the kitchen.

27

I eat three grape Popsicles for dinner and keep a few Cure songs playing over and over pretty loud so I won’t drive myself crazy trying to hear if my parents are talking about me. I don’t care about not getting along with them. I mean, it’s completely normal, right? I can’t think of anyone who always gets along with her parents. Ingrid used to fight with Susan and Mitch all the time, even though I thought they were pretty nice. Still, I keep waiting for a knock on my bedroom door because we’re just not like that, my parents and me. We snap at one another sometimes but we don’t really fight.

The knock comes about an hour later, just a light tapping on the door that I can’t hear over the music at first.

“Honey?” Mom says. “Someone’s here to see you.” I can tell from her voice that she’s just talking to me out of obligation. She hasn’t forgiven me yet.

I walk to my door and open it. My mom’s eyes are swollen and her mascara is smeared off. It hurts to look at her.

“Should I send him up?” she asks.

“Okay.” I peer skeptically at my sweatpants and ratty T-shirt; whoever it is, he is not going to see me at my best.

Mom patters back downstairs.

I hear her say, “Go on up. Last door on the left.”

Quickly, I throw the covers over my bed, trying to fake some semblance of order.

“Hey,” says a guy’s voice.

I turn around.

Taylor Riley is standing in my room.

“What are you doing here?”

“Oh,” he says, looking confused. “Well, we’re having a quiz tomorrow in precalc. He just announced it today. And it’s on the homework but you don’t know what the homework is, so I thought I should come tell you. You know, in case you wanted to, like, glance over it or something.”

I don’t answer him because I’m staring at his shirt. It says, in big letters across the front, Will WORK FOR SEX.

He looks at me. “What’s wrong? Is there something on my . . .”

He looks down at himself. I watch his face turn pink and then red.

“Oh my God,” he says. “Oh shit. I completely forgot I was wearing this. Oh my God, your mom. I can’t believe she let me into your room.”

He looks so embarrassed, and I would laugh except for how weirded out I am that he came over to my house to tell me about the homework.

“Do you think she noticed?” he asks.

“It’s kind of hard not to.”

“Yeah, but does she wear glasses usually? I mean, she wasn’t. So maybe she couldn’t really read it because it was blurry?”

I say, “She doesn’t wear glasses,” and I can’t help but laugh because he’s acting so funny and his face looks red next to his blond hair and those sideburns. “So what

is

the homework?”

“Pages eighty-seven to eighty-nine. Odd problems only,” he recites.

“Thanks.”

“Okay,” he says. “Well, you can study now.”

Then he pulls his shirt up over his head. I look at my feet. “What are you doing?”

“Turning my shirt inside out. Just in case I run into your dad on my way downstairs.”

“Why do you have that shirt anyway?”

He shrugs. “Jayson and I saw it in Berkeley at one of those T-shirt stores and I thought it was funny. I guess it’s kind of lame.”

I don’t want to think about Ingrid’s journal entry again, so instead I think about what I would do if Taylor started to kiss me. I imagine him reaching out for me. I would forget about everything bad for a little while.

My face gets hot. The real Taylor is right here, standing in front of me, apparently at a loss for words. Now his shirt says Xes ROF KROW LLIW.

“Thanks for giving me the assignment. I mean, it was kind of weird for you to just show up here. But, thanks.”

“No worries,” he says. He turns and walks to my door and stops.

Then he says, “That thing you told me about Ingrid? I guess that was your way of telling me that it was jacked up of me to ask how she did it. So I guess I also came to tell you that I’m sorry if it seemed like that to you. I didn’t mean anything by it.” He stops and I can see that he’s thinking about something. Finally, he says, “It was harsh, though, the way you told me. I learned the stages of grief once. I think you might be in the anger stage.”

He says it from across the room, but it feels like he just reached out, grabbed me by the throat, and squeezed me there. I feel my eyes well up. I can’t think of anything to say to him, so I just look at the carpet and he says, “See you,” and then I’m alone in my room again.

I retrieve Ingrid’s journal, ready to break my one-entry-a-day rule. But then I put it down. I need something that will listen and talk back. I rifle through my drawer for the school directory and open it to

Schuster.

There’s Dylan’s number next to a pixelated photo of her glowering for the camera.

I recognize her voice when she answers. It isn’t low but it’s kind of raspy.

“Hi,” I say. “This is Caitlin.”

“Oh, hey,” she says, and I’m so thankful at the way she says it, like it’s totally normal for me to call her.

“So, um. I have to do this photo assignment tomorrow after school? And I was wondering if you might want to come with me. We could go to the noodle place or somewhere before.”

“Yeah, sounds good,” Dylan says. I hear her mumble something in the background. “So I’ll meet you at our lockers?”

“Okay, cool,” I say, and I’m glad she isn’t here to see me nodding my head up and down over and over like an idiot.

I hang up and go outside again, but this time I climb into my car. I turn the tape on and listen until I fall asleep.

28

I thought it would be easy to find a bad landscape, but it isn’t. Even things that are ugly and plain in real life look different once I’m looking through the camera. Everything small turns significant. The gaps between branches on a sad little shrub transform into a striking example of negative space. I pivot around to face the strip mall. I half expect some miracle, but it remains ugly through the lens. I’m about to snap a picture when Dylan stops me.

“Wait,” she says. “Your teacher’s going to think that you’re making a statement. She’s going to be like, ‘Caitlin, fabulous commentary on our consumerist culture,’ or something.”

I lower the camera. “You’re right. We need to find a place that’s all just dirt.”

Dylan sips her coffee, says, “There’s this place that’s like a block from my house where the land’s all leveled.”

We start walking.

Dylan lives in the opposite direction from me, on the newer side of town. The houses there are mostly huge. Some of them are trying to look Spanish with white stucco exteriors and clay tile roofs. Others are just gigantic, modern boxes.

We get there and stop. “This is exactly what I wanted,” I say, staring at a dirt lot.

“I think someone’s going to build a house here.”

I start messing with the aperture on my camera.

“What are you doing?”

“I want it to be overexposed and out of focus.”

Dylan laughs. “So why, exactly, do you want your picture to suck so badly?”

“The photo teacher hates me and I hate her.”

“Sounds healthy.”

Dylan watches me take a couple of pictures of the dirt. The light outside is just the way I want it—not too bright. The contrast of the dirt against the sky will be almost nonexistent. After I’ve snapped a couple shots, Dylan shakes her head.

“

Why

does she hate you?”

I try to think of a way to explain it that won’t make her freak out the way my parents did. I stop messing with the camera and sit down on the curb next to her.

“It’s hard to explain. I was in her class last year, with Ingrid. She was actually nice then. But Ingrid’s like this amazing photographer.” I stop. “Or she

was,

I mean. An amazing photographer. So Ms. Delani was really nice to me because I was always with Ingrid.”