Hold Still (10 page)

Authors: Nina Lacour

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Social Issues, #Friendship, #Suicide, #Depression & Mental Illness

“And she isn’t nice anymore?”

“She just completely ignores me.”

Dylan nods. She watches me closely. “Okay,” she finally says. “So you’re doing this to get her attention.”

“No,” I say, and it comes out a little harsher than I meant it to. “It’s just that I don’t see the point in trying to put effort into her class.”

Dylan leans back on the sidewalk and stares up at the sky. I untie my shoes and then tie them again, tighter.

“I don’t want to sound like an asshole or anything,” she says after a while, “but it seems like there’s more going on. We just walked half a mile so that you could take a picture of dirt. So it seems like you

are

putting effort into this. You really want to piss her off.”

“Oh,” I say. “So you’re an all-around genius? You don’t have to save it up for English papers?”

She laughs. “I’m thirsty, are you thirsty?”

We walk up one more block to Dylan’s house, which is smaller than the others, painted dark blue.

“You have an old house.”

“Yeah, my parents aren’t into these monstrosities,” she says, gesturing to the three-story beige houses that tower above her little one.

“Look,” she says. “We actually have a white picket fence. I told my parents that if they were going to move me to the suburbs, they’d better go all out. Watch: isn’t this fantastic?”

She stops on the sidewalk and then skips through the fence. And it

is

funny, Dylan in her dark, tough clothes, her messy hair, and smudged eye makeup, entering a white picket fence.

Dylan’s living room is decorated with all of these old prints that look kind of scientific. They each have one type of flower or fruit printed on them with the plant’s name in small letters across the bottom. When we get to her room, I look at the stuff on her desk as she puts her backpack down and takes off her sweater. She has a laptop and pad of paper and a mug with a bunch of pens in it. Next to it, there’s a photo in a thin, silver frame of a girl with short, light hair and a wide smile.

“Who’s this?” I ask her.

“That’s Maddy,” she says.

“Does she go to your old school?”

“Yeah.” Dylan opens a window by her bed. “We’ve been together for five months.”

“Wow,” I say. I start my crazy nodding. I can’t seem to stop or to think of anything else to say. I want her to know that I’m not weirded out or anything, so I say, “That’s really cool!” It comes out way too enthusiastically and Dylan raises an eyebrow at me.

I look at a bulletin board above her desk and see a picture of an adorable little boy. He’s wearing rain boots and playing in the sand. The photo has this old snapshot quality that I really wish I could pull off. It’s softly focused and the colors are muted in a way that makes me feel nostalgic just looking at it.

“I love this picture.”

Dylan looks at it, then looks away.

“Okay. Something to drink,” she says. “Follow me.”

We walk down the hall and into a kitchen with bright yellow walls and a million pots and pans hanging from a metal rack over the stove.

“Mom’s a cook. Like, as her job. She’s really into her kitchen. When we were looking for houses, my dad would go straight to the backyards, I would head back to check out the bedrooms, and my mom would go directly into the kitchens. This was the first house we all agreed on. So we took it.”

She grabs two glasses from a cabinet.

“Water? Juice? Soda?”

“Water’s good.”

“Plain or fizzy.”

“Fizzy.”

“So,” Dylan says, handing me a glass. “Do you want to go to the city with me tomorrow? I’m meeting Maddy and some of our friends.”

“Sure,” I say, and take a sip so she won’t see me smiling.

When I get home, I drop the camera off in my room and head back downstairs. I unlock the door to my car and climb into the backseat, but for some reason I can’t get comfortable. It feels kind of cramped or dark back there. I haul my backpack up to the front, and squeeze my way into the passenger seat. The view is different from up here—I can see more of the house, the patio. Actually, I can see more of everything.

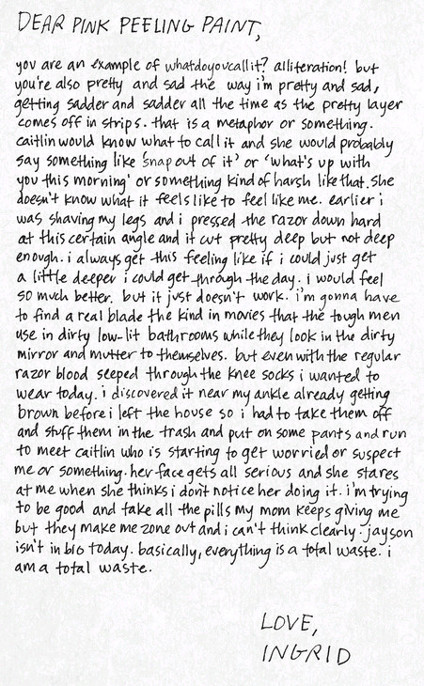

I take Ingrid’s journal out of my backpack, prop my knees on the dashboard, and read.

I finish reading and shove the journal into the glove compartment. I wish I knew why she never told me any of this. Maybe she thought I wouldn’t be able to handle it, that I was too sheltered or too innocent or something. If she had told me why she cut herself all the time, or that it was the pills that made her act so spaced out, or that she was even on pills, or even saw doctors, or

any

of it, I would have done my best to help her. I’m not saying I’m a superhero. I’m not saying I would have just swooped down and saved her. I’m just saying the only reason everything was a waste was that she made it a waste. That whole time, back when I was just a normal kid in high school, living out my normal life, I really thought everything mattered.

29

The next day in precalc, Taylor strides past his usual seat and takes the desk in front of me. He doesn’t say hi or anything. He just sits there with his back to me like it’s normal. Mr. James hands our quizzes back to us. I got an 89 percent. I scribble on my paper, trying to figure out the problems I missed.

Taylor turns around and stares down at my quiz.

“Hey, look,” he says. He shows me his. “We got the exact same grade. Crazy.”

“Yeah,” I say, kind of sarcastically, but I’m glad that he’s sitting here, talking to me.

“If anyone has any questions about the quiz, you can see me after class,” Mr. James says. “We’ll go over the homework in a few minutes, but first I want to introduce a new project. This will be a little different. I want you to find a partner and choose a mathematician from anywhere in the world—past or present—and prepare a presentation for the class that discusses the mathematician’s life, achievements, and historical and political setting.” He keeps talking about how math doesn’t only happen in classrooms, how it’s connected to everyday life. Taylor turns to face me again.

“Wanna work together?” he asks.

“Sure,” I whisper, and feel blood pump in my ears.

He turns back.

Mr. James says, “When you’ve broken into pairs, let me know.”

Taylor’s hand shoots into the air.

“Yes?”

“Me and Caitlin’ll work together,” he says, and then hunches over, suddenly fascinated by his quiz. I can feel the eyes of all the other students staring at us. My face feels hot.

But Mr. James, unaware that guys like Taylor are only supposed to want to work with the Alicia McIntoshes of the school, just mumbles, “Taylor and Caitlin,” and writes our names down, together, on a sheet of paper.

30

When I get to the library, Dylan is talking to the study-hall teacher, so I stay out of their way and look through a stack of art books.

I glance over at Dylan but she’s still talking. She sees me and mouths,

Just a second.

I start picking books off a stack. There’s one about Brazilian music and one about bridges and one about decorating small spaces.

Then I find one with a photo of a treehouse on the cover. I open it up, expecting to see all these simple treehouses built for little kids, but that’s not what the book’s about at all. These are real houses. People actually live in them, and they’re built up on high branches and they look amazing. They are tiny and private and warm. A bunch of them have built-in bookshelves and desks. I had no idea that treehouses like these existed.

Suddenly Dylan’s behind me.

“Hey,” she says. “Sorry. Ready to go?”

I don’t even look at her. I can’t stop looking through the pages of the book. Not only are there photographs, but there are lists of supplies you need to build your own, illustrated step-by-step directions.

All I can think about are the stacks and stacks of wood planks just waiting for me to put them to use.

“Let’s go, come on,” Dylan says.

“Okay,” I say. “Yeah. I just have to check this out first.”

31

When we walk up the escalator from underground at the Sixteenth and Mission BART station, there are panhandlers everywhere, asking us for money, food, cigarettes, to buy the papers they’re selling, to give them change for a BART ticket so they can get home. I feel caught in a stampede, but Dylan just handles them.

“Sorry, man,” she says to a boy who looks just a few years older than us, holding an angry dog on a leash.

To the ruder men who get up in our way as we’re walking, she says simple, hard no’s.

Whenever Ingrid and I got out of the suburbs, into Berkeley or San Francisco, and saw how other people lived, Ingrid would cry at the smallest things—a little boy walking home by himself, a stray cat with loose skin and fur draped over bones, a discarded cardboard sign saying HUNGRY please help. She would snap a picture, and by the time she lowered her camera, the tears would already be falling. I always felt kind of guilty that I didn’t feel as sad as she did, but now, watching Dylan, I think that’s probably a good thing. I mean, you see a million terrible things every day, on the news and in the paper, and in real life. I’m not saying that it’s stupid to feel sad, just that it would be impossible to let everything get to you and still get some sleep at night.

I walk fast with Dylan up Eighteenth to Valencia and then across to Guererro, until we finally reach Dolores Street and I see the park.

“This is my old school.” Dylan points to an old, grand building across from the public tennis courts and a bus shelter. “And those,” she says, pointing to a group of kids sitting under a tree, “are my friends.”

We walk toward them, and as we get closer, they come into focus: a boy with delicate arms wearing dark jeans that actually fit him, a couple—a boy and a girl—their backs against a tree trunk, their fingers clasped together.

“Dylan!” they all call out, their voices rising over one another’s.

I smile nervously. I can just tell from the way they’re sitting, so comfortably, that they’re so much cooler than I’ll ever be. They look different from the people at my school. My mom would say they look worldly.

Dylan and I sit down on the grass with them and I listen to them all talk. I don’t say anything but it’s not because they aren’t including me. It’s just nice to sit back and listen. Half of the conversation is directed to me. They tell me all these stories about themselves and one another. There is one about an all-night diner on Church Street, and how the boy in the jeans had a crush on a waitress who worked the night shift. He snuck out of his house every night and stayed for hours while she refilled his coffee.

“Oh!” he says, his face all lit up with excitement. “And here’s the best part: her name was Vicky. She wore this little apron over her skirt. It was so retro.”

“So what happened?” I ask. “Did you ever talk to her?”

“No,” he says, sighing. “She just stopped working. One night I went and she wasn’t there. And then she never came back again.”

“It was a tragedy,” Dylan says. “He’s never gotten over it.” She smirks at him and he swats her leg with his sweater.

They start another story. This one is about the couple, who have been together for almost a year, and the way the girl followed the guy for two quarters before finally having the courage to introduce herself. I lie on the grass with my head propped on my backpack and watch all the people walking by us on the grass. I imagine what it would be like to go to a school so big that people don’t know one another.

After a while it’s time to go meet Maddy at her job. We all stand up and walk to the edge of the park. They hug one another as I stand aside, and then they wave to me and we break off into three directions.

It’s just Dylan and me again. She rocks backward and then forward on her feet, puts her hands through her messy hair, and says, “We need coffee, right?”

Inside the café, Dylan pulls a silver cigarette holder from her back pocket. She snaps it open and I see a few rolled-up bills between its mirrored sides. She pays for her coffee and I buy a cookie, turn, and see her at a table peering into the cigarette case. She squints her eyes, opens them wide, and smears some black stuff around them. Then she snaps the case shut and starts tapping nervously against the table.

“Are you okay?” I ask her.

“Me? Yeah. Let’s walk.” She’s up and out the door in seconds and I’m dodging bicyclists and strollers trying to keep up.

We walk for a million sunny blocks, past palm trees and cafés and Laundromats, until we reach a small store on a corner. It’s red-and-white-striped, like an oversize, square candy cane with the words COPY cat painted on the front. We stop outside and Dylan looks at her reflection in the window. She moves a strand of hair away from her face and then moves it back. She turns around and announces, in a louder voice than usual, “Maddy’s shift should be over in two minutes.” She says this like I am part of a walking tour and Maddy is the most important of landmarks.

I start to think of how I could tease her about this, when the glass door opens and a girl with light, wavy hair walks out of the store. She has big dark eyes, and when she sees us a smile blooms across her face. And as Dylan turns to look at her, I watch this amazing thing happen. Dylan, in her skintight black jeans, safety-pinned shirt, and bulky armbands, with her hair sticking out in every direction and that black freshly smeared around her eyes, doesn’t just smile, doesn’t just walk toward Maddy and put her arms around her. No. Instead, every muscle in her whole body seems to lose all tension, her step forward resembles a skip, and she lets out a

hey

that might as well say

, I love you, you are so beautiful, no one in the world is as amazing as you are

.