Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State (50 page)

Read Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State Online

Authors: Götz Aly

BOOK: Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State

9.43Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Tooze, in the interest of “symmetry,” calculates the debts accrued by nations like France to pay wartime tributes to Germany in the same fashion as he reckons the Reich’s wartime debts to German banks, building societies, and insurance companies. He concludes, correctly, that both were forms of credit. But such formal criteria are irrelevant both here and in a number of other cases. The historical problem concerns something different. French contributions to Germany, regardless of how they were collected within France, represented real revenues for the Third Reich, from which ordinary Germans profited. Credit taken out on the German capital market to finance the war postponed the real burden upon the German people, and the goal was to transfer that burden, as quickly as possible, to enslaved peoples. This is why my calculations refer, as explicitly stated, to the Reich’s wartime revenues and not to its total expenditures.

A

FTER

I responded to his review of the German edition of this book,

*

Tooze wrote an article, citing Hitler’s finance minister von Krosigk to the effect that one could not use credit secured by the state to “defer” the burdens taken on by a borrowing country in times of war. At first glance, this seems a reasonable statement. Unlike a private borrower, who can, for example, buy a car on cheap credit and thus maintain his level of consumption basically unaffected, a nation waging war must restrict civilian consumption to compensate for credit-financed military consumption. But the hardships of war on the domestic front were significantly alleviated by selling off the belongings of dispossessed and murdered Jews, as well as of deported Poles and French citizens. Göring’s decrees of October 1940 lifting restrictions on what German soldiers could bring and send home from abroad also helped ease the situation. Every time soldiers used available spending money abroad and then sent the wares they bought back to Germany, they raised the real standard of living for their families.

FTER

I responded to his review of the German edition of this book,

*

Tooze wrote an article, citing Hitler’s finance minister von Krosigk to the effect that one could not use credit secured by the state to “defer” the burdens taken on by a borrowing country in times of war. At first glance, this seems a reasonable statement. Unlike a private borrower, who can, for example, buy a car on cheap credit and thus maintain his level of consumption basically unaffected, a nation waging war must restrict civilian consumption to compensate for credit-financed military consumption. But the hardships of war on the domestic front were significantly alleviated by selling off the belongings of dispossessed and murdered Jews, as well as of deported Poles and French citizens. Göring’s decrees of October 1940 lifting restrictions on what German soldiers could bring and send home from abroad also helped ease the situation. Every time soldiers used available spending money abroad and then sent the wares they bought back to Germany, they raised the real standard of living for their families.

It is hardly accidental that one of Germany’s leading postwar authors, Siegfried Lenz, should write in his 1966 essay “I, for Example: Characteristics of a Generation” that “everyone had a father, a brother or a brother-in-law in the war. Packages came with enchanting soaps from Paris, canned goods from Poland, reindeer ham from Norway and currants from Greece. The war was far away. It was going well and appeared as though it would be profitable. Our only taste of war, initially, was in such packages.”

*

Historians like Tooze and Overy, who focus only on Germany’s formal economy, ignore the phenomenon Lenz describes. Both treat the economic statistics for wartime Germany as if we were dealing with a transparent economy instead of one based on collective larceny.

*

Historians like Tooze and Overy, who focus only on Germany’s formal economy, ignore the phenomenon Lenz describes. Both treat the economic statistics for wartime Germany as if we were dealing with a transparent economy instead of one based on collective larceny.

For example, German ration cards for clothing provided 100 points per year. That was just about enough for a pair of shoes and a dress—not much and without a doubt less than what people enjoyed in Great Britain. But as we have seen throughout this book, soldiers often sent back quantities of clothing that greatly exceeded the official yearly allotment. It is thus misleading when Overy uses the nominal purchasing power of wartime ration cards as a measure of the standard of living in Germany. Using retail statistics, Overy concludes that the index of real per capita consumption fell by 30 points between 1938 and 1944, compared with only 12 points for Great Britain. That may be true, but a single home-leave visit by a heavily laden Wehrmacht soldier, a series of packages sent back from the front, and the state-sponsored auctions of Aryanized household effects easily sufficed to make up some of the difference. Some German soldiers and their families were even better off during the war than in peacetime. These factors may not show up in official statistics, but their significance cannot be denied.

My aim is to uncover the kleptocratic character of and the larcenous mechanisms within the National Socialist economy. Only when one does so, can one see how Nazi Germany shored up state revenues, domestic consumption, and public morale with policies of mass murder and state-organized plunder and terror. The consumer statistics cited by Overy do not reflect the day-to-day reality of the Nazi community of larceny, and thus objections raised to this book on the basis of those numbers are groundless. Overy and Tooze are more interested in the official statistics of Nazi Germany than in the de facto level of goods available to the German populace, which on the whole maintained its standard of living. In choosing to focus their work this way, they obscure rather than illuminate the way Germans actually lived during World War II.

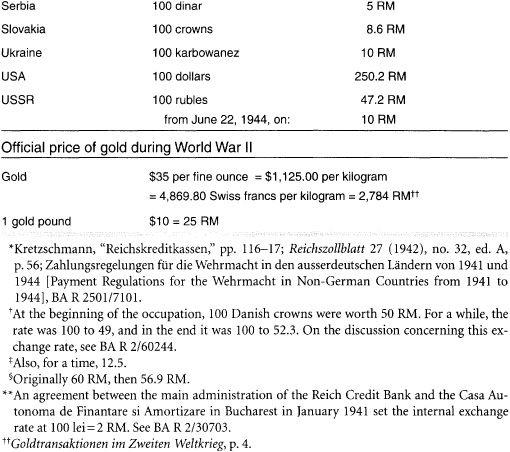

Currency Exchange Rates

Rates of exchange set by Germany, 1939–45*

List of Abbreviations

AN Archives Nationales, Paris

AOK Armeeoberkommando (Army Headquarters)

ASBI Archivio Storico Banca d’ltalia, Rome

AWA Allgemeines Wehrmachtamt (General Wehrmacht Office)

AWI Arbeitswissenschaftliches Institut der DAF (Labor-Scientific Office of the German Labor Front)

BA Bundesarchiv (Berlin-Lichterfelde and Koblenz)

BA-MA Bundesarchiv-Militärarchiv, Freiburg im Breisgau

BA-DH Bundesarchiv, Dahlwitz-Hoppegarten

DAF Deutsche Arbeitsfront (German Labor Front)

DSK Devisenschutzkommando (Currency Protection Command)

DVO Durchführungsverordnung (implementation ordinance)

DW Dienststelle Westen des RMfbdO (Western Office of the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories)

F (Lese-)Film (Microfiche)

FfW Forschungsstelle för Wehrwirtschaft (Research Group for Military Economics)

F.H.Q. Führerhauptquartier (Hitler’s Main Office)

GBW Generalbevollmächriger für die Kriegswirtschaft (general envoy for the war economy)

GG General Government of Poland

HA Hauptabteilung (Main Division)

HAdDB Historisches Archiv der Deutschen Bundesbank, Frankfurt am Main

H.V.B1. Heeresverordnungsblatt (Registry of Army Ordinances)

HZÄ Hauptzollämter (Main Customs Office)

Int. (intendant)

Kdo Kommando(sache) (command affair)

Kom. Kommandantur (Commandant’s Office)

KVR Kriegsverwaltungsrat (Wartime Administration Counsel/Council)

KWVO Kriegswirtschaftsverordnung (Wartime Economic Ordinance)

LArch Landesarchiv

LR Legationsrat (legation councilor)

Lt. Leitender, Leutnant (managing lieutenant)

MB, MBfh, Mil. Befh. Militärbe-fehlshaber (military commander)

MBB/NF Militärbefehlshaber in Belgien und Nordfrankreich (military commander in Belgium and northern France)

MBiF Militärbefehlshaber in Frank-reich (military commander in France)

MOL Magyar Országos Levéltár, Budapest (Hungarian State Archive)

MVB/NF Militärverwaltung Belgien und Nordfrankreich (military administration in Belgium and northern France)

MVAChef Militärverwaltung, Amtschef (military administration, office head)

MVOR Militärverwaltungsoberrat (military administration, superior counsel/council)

NA National Archives (and Records Administration), College Park, Maryland

NS Nationalsozialist (National Socialist)

NSB Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging (in den Niederlanden) (National Socialist Movement of the Netherlands)

NSDAP Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (National Socialist German Workers Party)

OB Oberbefehlshaber (commander in chief)

OFP Oberfinanzpräsident (chief financial officer)

Okdo Oberkommando (High Command)

OKH Oberkommando des Heeres (Army High Command)

OKM Oberkommando der Kriegsmarine (Navy High Command)

OKVR Oberkriegsverwaltungsrat (Superior Wartime Administration Counsel/Council)

OKW Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (Wehrmacht High Command)

OLG Oberlandesgericht (superior local court)

PA AA Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin (Political Archive of the German Foreign Office)

PK Parteikanzlei Hitlers (Hitler’s Party Chancellery)

RB (Deutsche) Reichsbank

RFM Reichsfinanzministerium, Reichsminister der Finanzen (Reich Finance Minister/Ministry)

RGBl. Reichsgesetzblatt (Reich Legal Registry)

RH Rechnungshof des Deutschen Reichs (Reich General Auditor’s Office)

RHK Reichshauptkasse (Reich treasury)

RK Reichskommissar, Reichskommissariat, Reichskanzlei, Reichskanzler (Reich commissioner, Reich Commissioner’s Office, Reich Chancellery, Reich chancellor)

RKG Reichskredit Gesellschaft AG (Reich Credit Union)

RKK Reichskreditkasse (Reich Credit Bank)

RKU Reichskommissariat Ukraine (Reich Commissioner’s Office for Ukraine)

RMfdbO Reichsministerium für die besetzten Ostgebiete (Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories)

RMI Reichsministerium des Inneren, Reichsminister des Inneren (Reich Interior Ministry/Minister)

RR Regierungsrat (government counsel/council)

RStBl. Reichssteuerblatt (Reich tax journal)

RTO Reichstarifordnung (Reich Tariff Ordinance)

RWM Reichswirtschaftsministerium (Reich Economics Ministry)

SAEF Service des archives économiques et financières, Savigny-le-Temple

SD Sicherheitsdienst der SS (Security Service of the SS)

Seetra Seetransport (-stelle) (Naval Transport Office)

SKL Seekriegsleitung (Directorate of Naval Warfare)

StA Staatsarchiv (state archive)

StS Staatssekretär (state secretary/deputy)

TB Tätigkeitsbericht(e) (progress report/s)

VO Verordnung (Decree/Ordinance)

VOBlF Verordnungsblatt des Militär-befehlshabers in Frankreich (Register of Ordinances by the Military Commander in France)

VOBlRProt Verordnungsblatt des Reichsprotektors in Böhmen und Mähren (Register of Ordinances by the Reich Protector in Bohemia and Moravia)

WaKo Waffenstillstandskommission (Armistice Commission)

WB, WBfh. Wehrmachtbefehlshaber (Wehrmacht commander)

WFStb Wehrmachtführungsstab (Wehrmacht Chiefs of Staff)

Wi Wirtschafts- (economic)

WO Wirtschaftsoffizier (economics officer)

ZFÄ Zollfahndungsämter (Customs Investigation Offices)

ZF Zollfahndung (customs investigation)

ZFS Zollfahndungsstelle (Customs Investigation Center/s)

ZNU Zentralnotenbank Ukraine (Central Currency Bank of Ukraine)

Notes

The prefixes PS, NG, NID, NO, and NOKW refer to transcripts of the Nuremberg trials, facsimile reproductions of which are available in most major research libraries. ET refers to Eichmann trial protocols and documents, similarly available.

PREFACE

Other books

Shades of the Past by Kathleen Kirkwood

The Beast by Jaden Wilkes

Warriors of Camlann by N. M. Browne

Outnumbered (Book 6) by Schobernd, Robert

The Temptation of Demetrio Vigil by Alisa Valdes

The Greek Billionaire's Love-Child by Sarah Morgan

The Moves Make the Man by Bruce Brooks

Vintage Volume Two by Lisa Suzanne

Junkyard Dog by Monique Polak

The Impossible Governess by Margaret Bennett