Hacking Politics: How Geeks, Progressives, the Tea Party, Gamers, Anarchists, and Suits Teamed Up to Defeat SOPA and Save the Internet (45 page)

Authors: and David Moon Patrick Ruffini David Segal

Tags: #Bisac Code 1: POL035000

Casey Rae-Hunter is a musician, recording engineer, educator, journalist and media pundit and the Deputy Director of the Future of Music Coalition, which took a strong stand against SOPA/PIPA. FMC is a national nonprofit organization that works to ensure a diverse musical culture where artists flourish, are compensated fairly for their work, and where fans can find the music they want. Rae-Hunter works alongside leaders in the music, arts, and performance sectors to bolster understanding of and engagement in key policy and technology issues, and has written dozens of articles on the impact of technology on the creative community

.

Music and protest have a long shared history. From Woody Guthrie to Dead Prez, artists have stepped up and used their voices to push back against the forces that seek to limit freedom and speech. And why not? Artists depend on free expression to create their next great song, movie, novel, or even video game.

And now, more than ever, this expression is connected to a digital infrastructure that lets artists spread their creativity to the entire world with the tap of a finger. When policies are proposed that could curtail the vibrant ecosystem of ideas we call the Internet, creators will cry foul, including many of the amazing artists and managers I have the privilege to work with as deputy director for the Future of Music Coalition.

Here in Washington D.C., debates about Internet policy and intellectual property enforcement are commonplace. These issues are often complex, but they nevertheless reflect some essential concerns shared by musicians and other artists. Namely, how to preserve an Internet that amplifies creativity and expression while encouraging lawful commerce. When the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) brouhaha erupted, my email inbox was quickly flooded with inquiries from musicians, music managers, arts organizations, professional writers and others who expressed unease about the scope of the proposed legislation. These are busy people, and it was telling that so many actually took the time to read the bill.

This is more than I can say for a lot of the well-compensated D.C. operatives who touted SOPA as a panacea to all the content industry’s problems. When I asked these folks to explain the more troubling aspects of the legislation, the least evasive answer I ever got was “we fix all that later; we need to pass something now.” In contrast, the artists I talked to were more than willing to probe deeper. That’s why you saw the direct involvement of Trent Reznor, MGMT, OK Go, the Flobots, Erin McKeown, Hank Shocklee, Jason Mraz, Zoe Keating and many more musicians, indie labels, authors, comics, graphic novelists, and designers.

Their concerns extend to the broader arts community, including the performing arts sector. These copyright holders are as much stakeholders as the

motion picture studios and major labels, and their perspectives must be considered in any debate around intellectual property. Arts organizations like Fractured Atlas are doing amazing work to ensure these important voices are heard, and they deserve recognition.

Make no mistake: protecting artists’ interests is incredibly important. Musicians and other creators depend on their intellectual property as part of how they earn a living. The stated goal of the SOPA and PROTECT IP—to fight back against commercially infringing sites based overseas—isn’t inherently insane. I’m a musician, and so are many of my friends. When we find our stuff on a sketchy foreign site that rakes in cash we’ll never see a penny of, we are understandably upset. The vast majority of artists aren’t rich, so the fact that there are commercial enterprises taking our creativity to the bank is deeply offensive. But so are policies that would compromise our ability to compete in today’s marketplace using the tools we’ve come to depend on.

At the end of the day, SOPA would have set limits on our own entrepreneurial and creative ambitions. And this is why so many of us in the creative community opposed this legislation.

In today’s dynamic digital environment, it’s hard to know what new platform will grow to be a powerhouse for creators. Who could have predicted the impact of YouTube, Twitter, Facebook, or Tumblr? Then there are the platforms that help musicians distribute their work to legitimate sites and services like iTunes, Amazon and Spotify. Had SOPA been in place a decade ago, commerce-facilitating sites like TuneCore and Topspin may have never gotten off the ground due to having to monitor all user activity for potential infringement. The legal costs alone would have likely made these sites unattractive to investors. And, even if they had gotten off the ground, it’s doubtful they’d have been able to provide a full suite of services to their users, which include countless musicians and other creators.

Any workable policy would protect expression without sacrificing the innovations that are so important to today’s creative landscape. SOPA was most certainly not it. Today’s artists understand intuitively how the Internet can leverage their creativity. What they really need are business models that better support their endeavors. You certainly don’t get there by placing heavy-handed mandates on emerging technologies.

In many ways, the goal of intellectual property enforcement could be made easier by taking a hard look at how music and other creative content is licensed. What we want are more legal services that compensate artists and where fans can find the music they love. This will require figuring out how to more quickly and efficiently get large catalogs of music from service to user. It is also true that certain licenses—like broadcast royalties, for example—are much easier to obtain and enforce. Furthermore, the task of safegurding copyrights is made even more difficult by the fact that isn’t always easy to know who owns what. It seems kind of crazy that, in an era of smart databases, there is no comprehensive authentication system for music. Addressing this would not only aid enforcement, but also help more artists get paid more often.

Now is the time for all stakeholders to come together to discuss how we can create a rising tide to lift all boats.

Which brings me to another point. In the post-SOPA spin cycle, some in the media were keen to paint this as a pitched battle between big content and big tech. The corporate entertainment industry was happy to play along, painting a conspiratorial picture of the protests. This was far from the case. First, the entertainment industry had quite a head start in terms of lobbying, having already poured millions of dollars into Washington before most of the tech companies even showed up. Second, the opposition to SOPA (and to a lesser extent, PIPA) was diverse, diffuse and powered from the bottom-up. I had a pretty good vantage point, and I recall the protests taking place in the following sequence: Tumblr self-censored; the reddit community started making noise; some time later Wikipedia went dark (but not before careful deliberation among its community). I think Google eventually put up a banner.

None of this was particularly coordinated, but all of it was democratically-driven. Can the MPAA say the same? It’s time to put the tall tales behind us. A false dichotomy between “content” and “tech” benefits no one, as these industries are inextricably linked. Without stuff to listen to and watch, today’s popular online hubs would be digital ghost towns. Without an efficient and powerful means with which to reach audiences, the creative sector would be at a permanent disadvantage. For all these reasons and more, it is incumbent on all participants in the digital ecosystem to find ways to work together. And from the artists’ point of view, it’s important that users consider more closely the impact of their online choices. Smarter business models and more attractive products and services will only get us halfway. We all need to do our part to ensure a sustainable online ecosystem that rewards creators, empowers fans, and inspires greater innovation. I believe that world is possible.

For me, the biggest takeaway from the SOPA skirmish is that artists and arts ambassadors will no longer stand for cultural policy being set by less than a handful of powerful Washington interests.

Our voices will be heard. We want to work with policymakers as well as the entertainment and technology industries to identify solutions. But we aren’t going to let any of these interests speak for us. We have our own voices, and can speak—and sing, and strum, and scratch—plenty loud.

ELIZABETH STARK

Elizabeth Stark has taught at Stanford and Yale about technology and the Internet, was one of the key organizers in the anti-SOPA movement that engaged eighteen million people worldwide, and has spent years working on open Internet issues, including cofounding the Open Video Alliance. She has researched and spoken on the future of knowledge and learning, serves as a mentor for the Thiel Fellowship, and is an Entrepreneur-in-Residence at Stanford’s StartX

.

It all started in about November. I had heard of this bill called SOPA—the Stop Online Piracy Act. And as I learned more about it, I knew it was really bad. When I say really, I mean really fucking bad. I have been a long-time open-Internet advocate, and many of my colleagues said, “This is the worst bill we have seen in the past decade.”

Here was a bill proposed by lobbyists of the content industry—in the U.S., the RIAA and MPAA; internationally, the IFPI and many more. They said it was about piracy, but it was really about something more. It was part of a war on sharing, a fight against the way that the open, distributed Internet works. It was a blatant attempt to preserve their business models to the detriment of artists, innovators, and the public at large. And it was poised to pass.

I called up some of my friends at Mozilla (you may have heard of their browser, Firefox) and said that we had to do something, and quick. So we held a small informal and interactive meeting of entrepreneurs, technologists, and activists to strategize on a plan. Fortunately, we had some people that worked for Congress in the room, and they told us, “This bill is pretty much a done deal. Unless you do something really huge, it will pass.”

And like that, the alarms went off. We had to do something huge. And luckily the Internet is the perfect platform for doing big things.

We decided on a strategy. On November 16, sites such as Mozilla, Tumblr, reddit, and even 4chan would blackout their logos in protest of SOPA. Fight for the Future set up a central site called American Censorship Day, where all the sites involved were listed. And there was a call for the Internet community to get involved. This was a watershed moment in the politics of the Internet: sites like Mozilla and Tumblr took a public stance for the first time ever on a political issue.

And on November 16 something huge did happen. Tumblr had built an incredible tool that enabled all its users to easily call their politicians. And like that, we had nearly one hundred thousand calls to Congress—quite possibly the largest number of calls that had ever been made to Congress in one day. We shut down the lines.

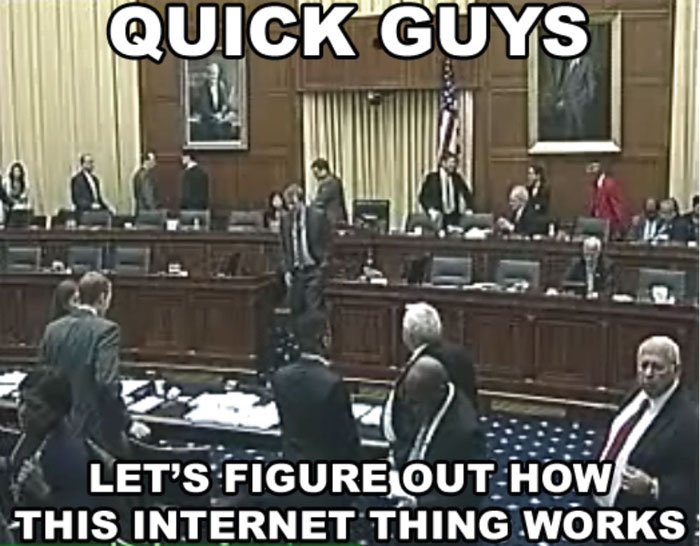

Things were looking pretty good, but the other side was ready to fight back. Round two came along: the SOPA markup hearing. Over two hundred thousand people watched the live stream of the hearing, and they tweeted and

laughed about it. Why were they laughing? It was so painfully obvious that the U.S. Congress, the people we entrust to create our laws, fundamentally did not understand the Internet.

There were members of Congress who had no idea what a domain name is, let alone how the Domain Name System, or DNS, works, voting on a bill that would change the very nature of this system. This was a huge wake up call. People were angry.

In one of the only planned moments of levity, Congressman Jared Polis, probably the person in Congress who knows the most about the Internet, proposed an amendment saying that SOPA should not be used for porn. Basically, he was trolling. He not only told Congress about the song “The Internet Is for Porn” but asked to enter it into the Congressional record.

As anger on the Internet rose, the ever-energetic reddit community decided to fight back. How? Shut down the site for an entire day. The Wikipedia community then decided to follow suit. As did Mozilla, Google, Tumblr, I Can Haz Cheeseburger, and many, many more. All in all, over eighteen million people took action. Hell, even my mom told me that she “voted” for “privacy” (not quite Mom, but thanks for the support!).