Hacking Politics: How Geeks, Progressives, the Tea Party, Gamers, Anarchists, and Suits Teamed Up to Defeat SOPA and Save the Internet (21 page)

Authors: and David Moon Patrick Ruffini David Segal

Tags: #Bisac Code 1: POL035000

We didn’t realize this phenomenon had a name until reading the recent book, Bailout, by Neil Barofsky, who was the inspector general of the Toxic Assets Relief Program (TARP), or what most of us know as the bank bailout. It’s generally understood in political circles that it is folly to “punch down”: you don’t attack somebody who’s lower than you on the totem pole, or it gives your antagonist a chance to drag you down to their level and advance their cause.

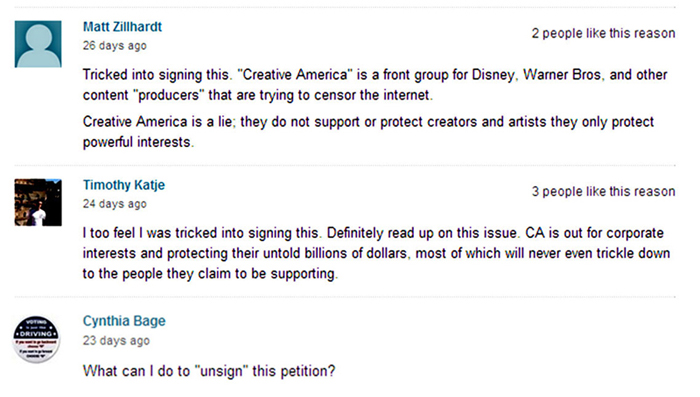

And drag them down we did, gleefully using these attacks to excite our members and grow our organization. The Chamber of Commerce’s maniacal post became fodder for a fundraising appeal to our membership, and raised several thousand dollars. A few months after it launched, Creative America—an AstroTurf (faux grassroots) group that was funded by the major Hollywood studios—announced that it had achieved a membership of ten thousand PIPA supporters. We pushed our list to help us recruit ten thousand new PIPA opponents (deemed such once they’d emailed the Senate against the bill) in 24 hours. It took 72.

Buyer’s remorse: These screenshots capture a few comments of those who signed a petition in support of Creative America on the

Change.org

website - and later realized they’d been tricked into backing a corporate front group’s effort to censor the Internet.

Along the way we struggled to peel labor organizations away from the SOPA/PIPA sponsors’ spin about the issue. But on the ground, union members working in creative industries often sympathized with the fight to keep the Internet open. This Screen Actors Guild member notes his opposition to SOPA at the Jan. 18, 2012 NY Tech Emergency Meetup.

DAVID SEGAL

As I’ve set about editing this book I’ve noticed that several essays espouse—or at least seem situated upon a background of—the libertarian economic tendencies that comport with the leanings of many people in the tech community. Let me try to add some balance.

I ran for city council in 2002 spurred in large part by a living wage organizing campaign in Providence, led by labor vanguard groups like Rhode Island Jobs with Justice and unions like the Service Employees International Union and the Hotel and Restaurant Employees Union. We were striving to enact legislation that would guarantee that full-time employees for the city and major city contractors earn at least $10.19 per hour—not much to ask for in high-cost New England. Our efforts to pass the ordinance fell just short—our mayor flipped his position on the issue and brought a key councilmember with him—but several bargaining units that would have benefited from the law organized into unions and achieved wages at that level or higher through collective bargaining, and many of the activists who cut their teeth in that effort still serve as the heart of Providence’s progressive activist community. Over the course of my near-decade in politics I racked up a 100% voting record as per the various unions’ legislative scorecards, was endorsed by several major unions for my Congressional run in 2010, and regularly wore a Jobs with Justice hooded sweatshirt on the floor of the House of Reps. (I was pretty poor—we made about $14,000 to serve in the Assembly—and there’s a certain power of notoriety that follows from underdressing.)

As I closed out my tenure as a state rep in late 2010, it was thus terribly awkward to find that I was now lined up against much of organized labor, as unions stood with Hollywood and other business interests as they opposed the efforts of millions of Americans—including myriad union members—to defend the open Internet.

Silicon Valley tends to hold quite liberal positions on matters of social policy, to which I absolutely adhere: support for gay rights, drug policy and broader criminal justice reform, less militarism, and the like. But a substantial sub-portion of tech tends towards an anarcho-capitalist economic vision whereby an optimal society is one in which perfectly networked people-points engage in frictionless commerce, with very low taxes and a minimal social safety net, and in which unions—were they ever useful—are endemic to the ossified industrial structures that governed the Old Economy, and whose agitation unduly protects incumbents and generates economic inefficiencies. This is, in fact, much of the essence of the so-called California Ideology, an influential strain of Cyber Utopianism. (For a detailed historiography of these tendencies, watch any—ideally all—of Adam Curtis’s wonderful films, especially

All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace

.)

I am not a Cyber Utopian. I think the Internet is critically important and has, and will continue to, improve peoples’ lives the world round—but only so long as we fight to make sure it remains a force for the democratization of society, rather than a tool that the already-powerful can use to entrench themselves. The Internet can create efficiencies and reduce costs, but it doesn’t inherently serve to reduce inequalities or otherwise create a more economically just society.

Government intervention in the economy is imperative to its functioning in any remotely humane fashion. Organized labor is as needed as ever, its atrophy over recent decades coinciding with, and helping stir, a vicious cycle that’s led to vast wealth inequality. Just a small percentage of the last 40 years’ worth of productivity gains have accrued to the average worker, with real-dollar median wages growing by about 20% while real GDP has doubled. The so-called economic recovery in whose midst we still struggle, four years on from the collapse, has skewed wealth distribution even further towards the already wealthy: the rich have scrabbled back to where they stood pre-recession far faster than the rest of us. This is, in part, a direct consequence of the labor movement’s too-limited influence over governmental decisions and boss-employee power dynamics: labor’s weakened bargaining position within the workplace has made it easier for management to keep the bulk of profits for themselves, reducing employees’ quality of life, and meaning that there’s less money in the hands of people who are actually likely to spend it in the real economy.

Labor’s diminished power over political actors is much of why the government’s reaction to the economic crisis has been so pathetic. Deficit spending that’s too little to replace lost demand—and insufficient to compel banks and the wealthy to recommence lending—has enabled a collapse in government revenues, which has, in turn, led to the elimination of public employees’ jobs, remaining workers’ income growth stalling out, and waves of panic over pension liabilities that wouldn’t be a substantial burden under more sane national-level economic leadership. Now even Social Security and Medicare look likely to fall beneath lawmakers’ axes.

Even were we all, indeed, the rational, omniscient, self-interested atoms posited by the California Ideology, it’s clear that many economic problems would best be solved through collective action. Two illustrations that I hope might appeal to my data-driven friends in Silicon Valley and Alley follow.

First of all: there’s an essential game theory problem that helps sustain the decrepit state of our economy—it can be illuminated by that most canonical game theory thought experiment, in fact: in the Prisoners’ Dilemma, two partners in crime are hauled into jail and separated for questioning. If one snitches and the other doesn’t, the rat walks and the one who stays quiet goes to jail for ten years; if each gives up the other, they both go to jail for three years; if neither talks, they both go free. In the Prisoner’s Dilemma the rational decision, yielding the best-expected outcome for each criminal, has the pair ratting one another out, and taking the middling sentences. It’s a tragic (for the criminals) function of the inability to engage in collective action, as in a world in which the duo could communicate with and trust one another they’d both keep their lips sealed and neither would go to prison at all.

Lack of confidence that investments in a struggling economy will pay off is a partial explanation for ongoing hoarding and liquidity traps. Nobody wants to stick their neck out on their own, without an understanding that other lenders are likely to start lending, and that consumers are likely to consume. Just as the prisoners would optimize their respective outcomes were they able to confer and act in a binding unison by which they agreed to stay mum, so too would our economy be best off if all of the economic actors agreed that they’d spend together, and kick-start a real recovery. That’s another way of looking at some of the effects of deficit spending: a form of enforceable collective action, decided upon through the deliberation of our (somewhat) democratic governmental institutions.

This is not to say that our government’s actions are determined in an altruistic fashion with the public welfare as decision makers’ highest end—quite frequently the opposite, in fact. Which puts me and my progressive allies in the awkward position of arguing for the importance of intervention by a government that’s so clearly corrupted by the overbearing influence of the wealthiest, many of whom strive to manipulate the levers of power towards the end of self enrichment and protection of the incumbent institutions that helped them achieve their riches to being with. We can surely improve upon this dynamic: public financing of elections, with one innovative such scheme proposed later in this book, would go a long way. It’s not hard to see why many don’t trust the government to help solve our economic problems, but the government’s current failings don’t mean that a near government-less society would yield better outcomes.

Secondly: During my time spent with the tech community I’ve heard many stirring soliloquies about Creative Destruction and the benefits that would flow to all humankind—new efficiencies, consumer surplus—were we to institute unfettered, no-holds-barred capitalism and just let ‘er rip. But to engage in such paeans to capitalism is to recognize—and specifically lionize—the most brutal structural aspects thereof. Industries rise and fall, taking with them the livelihoods of untold workers who’ve invested their lives therein. If a given industry is in such a precipitous collapse its workers may have no other skills to parlay into basic sustenance, at no fault of their own. This is all the more reason for those who care about their fellow human beings to want to see a strong social safety net—even the likes of Hayek and Friedman, who are invoked as the spiritual leaders of so many on the modern Right, understood as much. There’s also a modicum of rational self interest to be had here: if workers weren’t (rightfully) scared to death at the prospect of losing employment, they might do less to seek government subsidy for industries that were in decline or in need of stark changes to their business models. Ahem … Hollywood? Or the hotel industry, from the perspective of bed-and-breakfast facilitator Airbnb, or the taxi industry, from the vantage of the on-demand car service Uber, and on and on.

Specifically, government guarantees of health care—a Medicare-for-all program, more efficient than the private insurance system—and pensions more robust than Social Security—would give Americans some assurance that they wouldn’t starve. They’d enable entrepreneurship, as health care access is a concern that forces people to scurry towards and hold onto jobs they don’t want

instead of starting their own shops (though this predicament will be somewhat improved under Obamacare). The appropriate societal response to hard economic times and workers’ desires for portable retirement plans isn’t to convert traditional pensions into 401(k)s—rather, it’s to institute a robust federal pension system. A step between here and there would be to adopt the plans most Europeans have access to—much more robust even under austerity than the crumbs we toss at American seniors. Such programs would also relieve employers of the burdens of carrying the cost of benefits and would generate economies of scale from which society doesn’t benefit at present.

Some would assert that resources are scarce, that we must learn to do more with less. To the extent to which this is the case, it’s a function of decisions made by politicians and financiers, not of fundamental economic limitations. Global warming and other physical resource constraints can be limiting factors, but in no meaningful respect is this what political actors with any standing consider when they make arguments about the supposed need to cut government spending. (For a better understanding of how government spending works, read the writing of any economist who identifies with the Modern Monetarist school.)