Hacking Politics: How Geeks, Progressives, the Tea Party, Gamers, Anarchists, and Suits Teamed Up to Defeat SOPA and Save the Internet (43 page)

Authors: and David Moon Patrick Ruffini David Segal

Tags: #Bisac Code 1: POL035000

And there are no permanent allegiances or mutual back-scratching. Google has been on both sides of similar, albeit smaller, outbursts, as has Apple, Facebook, and other leading technology companies. In their stampede for Internet freedom, users will trample anyone perceived to stand in the way—Republicans, Democrats, mainstream media, technology companies, industry groups, and governments from local to international.

In the bitroots community, engineers play a unique role as trusted and objective commentators on what is and is not good for the Internet’s underlying technology. They are the shamans who interpret the cryptic (and encrypted) messages of the gods, and they must be consulted before making any great

or small change to the architecture that has delivered the users into the new world.

Engineers are trusted because they have proven themselves objective. They simply don’t have the capacity for double-talk. Ask them how the network will respond to a proposed alteration—whether of technology or law—and they will tell you. Their candor may be novel for those used to governments built on subterfuge, but that doesn’t make it any less valuable.

One of the unforgivable sins of the PIPA and SOPA process, consequently, was a complete failure to engage with anyone in the engineering community; what lawmakers on both sides of the issue regularly referred to as “bringing in the nerds.”

And engineers were essential to getting it right, assuming that’s what the bills’ supporters really wanted to do. Both bills would have required ISPs to make significant changes to key Internet design principles—notably the process for translating web addresses to actual servers. Yet lawmakers freely admitted that they understood nothing of how that technology worked. Indeed, many seemed to think it was cute to begin their comments by confessing they’d never used, let alone studied, the infrastructure with which they were casually tinkering.

Internet users have revolted in the face of earlier efforts to regulate their activities, but never on this scale or with this kind of momentum. Perhaps that’s because PIPA and SOPA presented a perfect storm. The draft legislation was terrible, the legislative process was cynical and undemocratic, and the public relations efforts of supporters fell flat on every level.

Yet it’s already clear that the losers in the PIPA/SOPA fight have learned nothing from the profound activation of Internet users. Rep. Lamar Smith, SOPA’s chief sponsor, dismissed the Wikipedia blackout as a “publicity stunt,” while Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.), PIPA’s author, blamed defecting Republicans (defections were bi-partisan, as was opposition to both bills from the beginning). And supporters are already looking for opportunities to snatch victory from the jaws of defeat. “My hope is that after a brief delay, we will, together, confront this problem,” Leahy said yesterday.

The content industry has proven equally tone deaf. Speaking at the Sundance Film Festival, MPAA President (and former senator) Chris Dodd called the protests “white noise” that “has made it impossible to have a conversation.” That is, now that the industry has deigned to lower itself to having a conversation at all.

John Fithian, CEO of the National Association of Theatre Owners, unintentionally summed up everything that was wrong with the process from the beginning: “The backlash occurred,” he said, “Google made its point, they’re big and tough and we get it. Hopefully now reasonable minds will prevail.”

They don’t get it at all. It wasn’t Google who made “the point,” it was the company’s millions of users. The sponsors of SOPA and PIPA don’t even know

who stopped them cold. But supporters of the proposed laws are retrenching anyway, preparing to launch a new assault on an enemy it hasn’t identified.

Given both their arrogance and ignorance, it goes without saying that the content industries are unlikely to avoid similar catastrophes in the future, let alone find a way to work collaboratively with a political force they don’t know—or believe—exists.

On the other side, it’s hardly time to declare victory and go home. The SOPA win aside, the future success of the bitroots movement is far from certain. Whether the next issue is rogue websites, electronic surveillance, FCC oversight or government censorship (foreign or domestic), it may not always be so easy to call the Internet faithful to put up a united front.

Right now, it takes little more than a few key phrases—“open,” “censorship,” “privacy,” “break the Internet”—to hook the outrage of the Internet masses. But maintaining momentum requires something more sophisticated. And the accusations have to prove true.

To become a permanent counterbalance to traditional governments, the bitroots movement will need to become more nuanced and more proactive. To avoid the very real possibility of mob rule, Internet activists must use their power responsibly. SOPA was a gimme. But legislators and regulators won’t go quietly from this or future efforts to exert their influence over the Internet.

As the information economy increasingly becomes the economy that matters, we’ll need to find ways to accommodate Internet values to traditional rulemaking, to bridge the expanding chasm between Capitol Hill and Silicon Valley. The stakes are high—the future of the economy as well as the technology depends on getting it right. We can’t afford to mess it up. And we can’t afford to dismiss the bitroots movement as a sporadic, random outburst.

It’s worth remembering that some legislative interference has been valuable to the infant digital economy. These include protections in the U.S. against holding websites responsible for third party content (hard to imagine Facebook or Twitter or reddit existing without that) and laws that minimize the authority of the Federal Communications Commission to work its particular brand of poison against broadband providers (they still oversee dial-up Internet services, and look how healthy that is).

Those acts of happy foresight seem far from the minds of tomorrow’s would-be regulators, however. In an interview Thursday, former Senator Dodd called for a summit between “Internet companies” and content companies, in hopes of finding a compromise on PIPA and SOPA. “The perfect place to do it is a block away from here,” said Dodd, pointing to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue.

No, Mr. Dodd, the White House is not the “perfect place” to engage with Internet companies. And it isn’t the companies who matter the most. If you really want a “conversation,” you need to engage with Internet users, and you need to do so nearly anywhere except inside the beltway.

The only place to really engage your new adversaries is where they live—online, in chat rooms and user forums and social networks, on Twitter and

Facebook and Tumblr and reddit and whatever comes next. If you want to understand what went so horribly wrong with your business-as-usual efforts, you’ll need to take up residence in the digital realm and learn its new rules of engagement.

And if you want to persuade Internet users to help you innovate solutions for your industry’s many problems, you’ll need to come without your handlers and spin doctors, and without any expectation that your credentials or past accomplishments will carry weight in a serious debate about the costs and benefits of changing the architecture of the Internet to reduce copyright infringement. Come armed with facts, not rhetoric. Bring an open mind. And some engineers.

Oh, and if you’re serious about making real progress, stop calling us nerds.

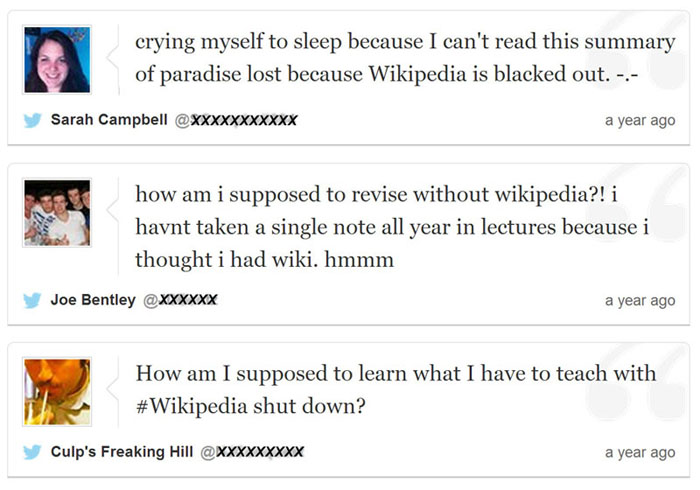

The Wikipedia blackout had countless grade school students in a frenzy, and many of them took to Twitter to express their frustration. These are a few of the best, as curated by

Gawker.com

.

EDWARD J. BLACK

Edward Black is the President and CEO of the Computer & Communications Industry Association. CCIA is a nonprofit membership organization for a wide range of companies in the computer, internet, information technology, and telecommunications industries, represented by their senior executives. Created over four decades ago, CCIA promotes open markets, open systems, open networks, and full, fair, and open competition. The organization was an early outspoken opponent to SOPA/PIPA

.

Legislative fights are like icebergs: a lot happens underwater for every issue that breaks through to the surface. Legislative battles over intellectual property rarely evolve to the point of making front-page headlines as they did in the case of the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA).

SOPA became a lead story because it represented not just a battle among industry sectors over policing the Internet for copyright infringement, but an ongoing fight over the future of the Internet that impacts millions of users.

The public saw the House Judiciary Committee wrangle over cyber security and private censorship provisions during the markup of SOPA in December 2011. Tech reporters and bloggers wrote about how lawmakers—some of whom did not appear to understand how the Internet worked—were pushing legislation that would drastically regulate the web. Public outrage built up over the holiday break until the Internet blackout in mid-January 2012 became a top story on CNN and other major news outlets.

But the key underlying debate had been building for nearly two decades. The central question of that debate is to what degree Internet companies and businesses should become privatized Internet police.

While this debate wore on, the Internet itself continued to change. The Internet is no longer composed primarily of static websites that offer information to users. Today, the successful business model for many of the companies that my organization, the Computer and Communications Industry Association, represents is to build platforms that empower Internet user participation.

This question of deputizing Internet companies to monitor their users is anathema to industry for a few reasons. First, no one wants to be in the business of spying on customers. Second, business models that empower millions of users’ communications and commerce would no longer be viable if companies had the added mandate to thoroughly police that sheer volume of content. Nevertheless, politically established corporate rights holders—from Hollywood, to the recording industry, to the Chamber of Commerce—have long sought to shift to online platforms the cost and responsibility of identifying material that may have infringed intellectual property rights.

Four years before the SOPA standoff, the online copyright issue first gained traction on Capitol Hill among a few members of Congress who were preparing to introduce rights-holder-backed legislation called the Combating Online Infringement and Counterfeiting Act. (COICA). The bill would have created blacklists of websites and the U.S. Attorney General would have then required Internet service providers, advertisers, and others to stop doing business with these sites.

This proposal would have weakened the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) “safe harbor” provision that gives Internet companies legal protection from liability for what others do on their sites—as long as companies quickly remove infringing content once it is reported. With COICA, copyright extremists instead wanted Internet platforms to proactively guess whether content might be infringing, and risk prosecution if they failed to remove it.

The lobbying challenge for technology companies was to combat misinformation about the scope of the infringement problem and to offer appropriate remedies that wouldn’t have broad consequences for legitimate e-commerce or the smooth functioning of the Internet. Our industry explained that having a U.S. blacklist for seemingly legitimate reasons like combating piracy gives the green light to Internet restricting countries to have their own blacklists for more nefarious reasons. Such policy is at odds with our diplomatic agenda, which discourages Internet filtering and censorship.

In the case of SOPA and its Senate companion the PIPA, the entertainment industry asked Congress to require that tech companies take on the crippling responsibility of proactively monitoring and controlling all the content and conduct that passes, even momentarily, through their sites and services. This would be achieved by gutting the liability protections that current DMCA law provides to tech companies that quickly respond to notices of copyright violations and remove such content.

SOPA was even more heavy-handed than COICA and would have also conflicted with new security protocols the government developed to curb phishing and spam. It would have required Internet companies to redirect Internet traffic from sites users requested.

If SOPA were to have passed it is within reason to believe—depending on how the Courts interpreted “engage in, enable, or facilitate” copyright infringement—that Facebook posts, Twitter links, and really any Internet service or app that allows a user to post and others to view would have to screen material. A site like YouTube would need to preview the 72 hours of video uploaded each minute, and then approve the video. The companies would have to screen material either manually or using automatic filters with high false positive rates and no real way to check for “fair use.” They would have done this filtering either preemptively or very quickly after it was posted.