Gulag (48 page)

9b

Entrance to a Vorkuta lagpunkt (the sign reads: “Work in the USSR is a matter of Honour and Glory . . .”)

10a

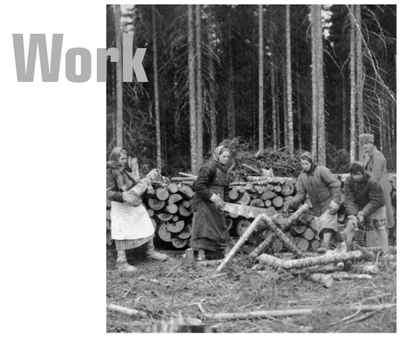

Sawing logs

10b

Hauling timber

11a

Digging the Fergana Canal

11b

Digging coal

12a

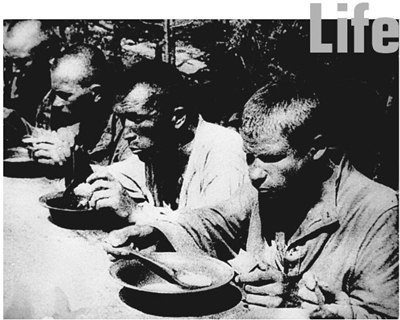

“If you have your own bowl, you get the first portions.”

12b

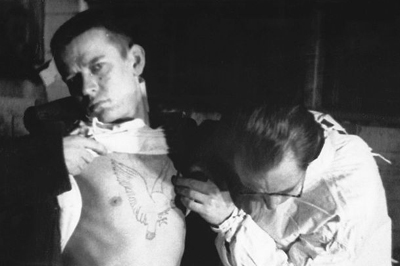

“They surrendered their bronze skin to tattooing and in this way gradually satisfied their artistic, their erotic, and even their moral needs.”

13a

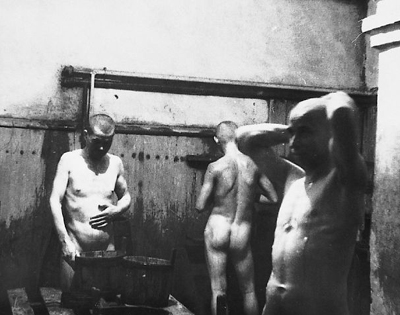

“We picked up a wooden tub, received a cup of hot water, a cup of cold water, and a small piece of black, evil-smelling soap . . .”

13b

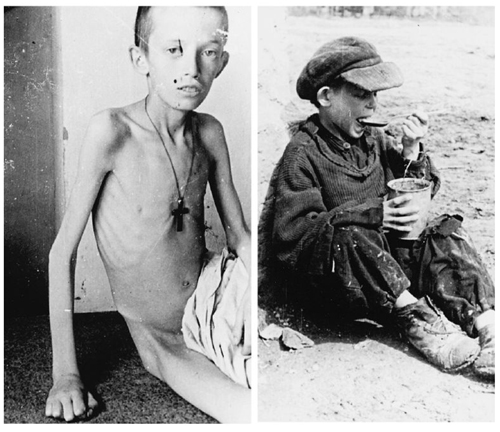

“Having been admitted with advanced signs of malnutrition, the majority would die in hospital . . .”

14a&b

Polish children, photographed just after amnesty, 1941

15a

Camp maternity ward: a prisoner nursing her newborn

15b

Camp nursery: decorating a holiday tree

16a

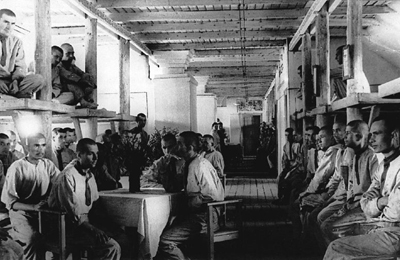

A crowded barracks . . .

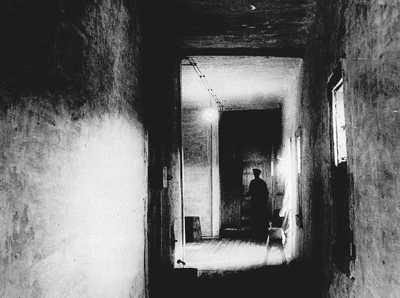

16 b

. . . a punishment isolator

Chapter 15

WOMEN AND CHILDREN

. . . the prisoner who was our barrack orderly greeted me

with a cry: “Run and see what’s under your pillow!”

My heart leaped: perhaps I’d got my bread ration after all!

I ran to my bed and threw off the pillow. Under it lay three

letters from home, three whole letters! It was six months since

I’d received anything at all.

My first reaction on seeing them was acute disappointment.

And then—horror.

What had become of me if a piece of bread was worth more

to me now than letters from my mother, my father, my children. . . . I forgot all about the bread and wept.

—Olga Adamova-Sliozberg, My Journey

1

THEY MET the same work norms and they ate the same watery soup. They lived in the same sort of barracks and traveled in the same cattle trains. Their clothes were almost identical, their shoes equally inadequate. They were treated no differently under interrogation. And yet—men’s and women’s camp experiences were not quite the same.

Certainly many women survivors are convinced that there were great advantages to being female within the camp system. Women were better at taking care of themselves, better at keeping their clothes patched and their hair clean. They seemed better able to subsist on low amounts of food, and did not succumb so easily to pellagra and the other diseases of starvation.

2

They formed powerful friendships, and helped one another in ways that male prisoners did not. Margarete Buber-Neumann records that one of the women arrested with her in Butyrka prison had been picked up in a light summer dress which had turned to rags. The cell determined to make her a new dress:

They clubbed together and bought half-a-dozen towels of rough, unbleached Russian linen. But how was the dress to be cut without a pair of scissors? A little ingenuity solved the problem. The “cut” was marked with the burnt ends of matches, the material was folded along the marked lines, and a lighted match was run backwards and forwards for a moment or two along the fold. Then the material was unfolded again and the line was burnt through. The cotton for sewing was obtained by carefully withdrawing threads from other clothing . . .

The towel dress—it was made for a fat Lettish woman—went from hand to hand and was beautifully embroidered at the neck, the sleeves, and round the bottom of the skirt. When it was finally finished it was dampened down and carefully folded. The fortunate possessor slept on it at night. Believe it or not, but when it was produced in the morning, it was really delightful; it would not have disgraced the window of a fashionable dress shop.

3

Nevertheless, among many male ex-prisoners the opposite point of view prevails: that women deteriorated, morally, more rapidly than men. Thanks to their sex they had special opportunities to obtain a better work classification, an easier job, and with it superior status in the camp. As a result, they became disoriented, losing their bearings in the harsh world of the camp. Gustav Herling writes, for example, of a “black-haired singer of the Moscow Opera,” who was arrested for “espionage.” Because of the severity of her sentence, she was assigned immediately to work in the forest upon her arrival in Kargopollag:

Unfortunately for her, she was desired by Vanya, the short

urka

in charge of her brigade, and she was put to work clearing felled fir trees of bark with a huge axe she could hardly lift. Lagging several yards behind the hefty foresters, she arrived in the zone in the evening with hardly enough strength left to crawl to the kitchen and collect her “first cauldron” [the lowest-level soup ration] . . . it was obvious that she had a high temperature, but the medical orderly was a friend of Vanya’s and would not free her from work . . .

Eventually, she gave in, first to Vanya, then finally to “some camp chief” who “dragged her out by the hair from the rubbish heap and placed her behind a table in the camp accountant’s office.”

4

There were worse fates too, as Herling also describes. He gives, for example, an account of a young Polish girl, whom an “informal jury of

urkas

” rated very highly. At first, she walked out to work with her head raised proudly, and repulsed any man who ventured near her, with darting, angry looks. In the evenings she returned from work rather more humbly, but still untouchable and modestly haughty. She went straight from the guard-house to the kitchen for her portion of soup, and did not leave the women’s barracks again during the night. Therefore it looked as if she would not quickly fall a victim to the night hunts of the camp zone.

But these early efforts were in vain. After weeks of being carefully watched by her supervisor, who forbade her to steal a single carrot or rotten potato from the food warehouse where she worked, the girl gave in. One evening, the man came into Herling’s barracks and “without a word threw a torn pair of knickers on my bunk.” It was the beginning of her transformation:

From that time the girl underwent a complete change. She never hurried to get her soup from the kitchen as before, but after her return from work wandered about the camp zone till late at night like a cat in heat. Whoever wanted to could have her, on a bunk, under the bunk, in the separate cubicles of the technical experts, or in the clothing store. Whenever she met me, she turned her head aside, and tightened her lips convulsively. Once, entering the potato store at the center, I found her on a pile of potatoes with the brigadier of the 56th, the hunchbacked half-breed Levkovich; she burst into a spasmodic fit of weeping, and as she returned to the camp zone in the evening she held back her tears with two tiny fists . . .

5

That is Herling’s version of a frequently told story—one which, it must be said, always sounds somewhat different when told from the woman’s point of view. Another version, for example, is recounted by Tamara Ruzhnevits, whose camp “romance” began with a letter, a “standard love letter, a pure camp letter,” from Sasha, a young man whose cushy cobbler’s job made him a part of the camp aristocracy. It was a short, blunt letter: “Let’s live together, and I’ll help you.” A few days after sending it, Sasha pulled Ruzhnevits aside, wanting to know the answer. “Will you live with me or not?” he asked. She said no. He beat her up with a metal stave. Then he carried her to the hospital (where his special cobbler’s status gave him influence) and instructed the staff to take good care of her. There she remained, recovering from her wounds, for several days. Upon release, having had plenty of time to think about it, she then returned to Sasha. Otherwise, he would have beaten her up again.

“Thus began my family life,” wrote Ruzhnevits. The benefits were immediate: “I got healthier, walked about in nice shoes, no longer wore the devil knows what kind of rags: I had a new jacket, new trousers . . . I even had a new hat.” Many decades later, Ruzhnevits described Sasha as “my first, genuine true love.” Unfortunately, he was soon sent away to another camp, and she never saw him again. Worse, the man responsible for Sasha’s transfer also desired her. As there was “no way out,” she began sleeping with him too. While she does not write of feeling any love for him, she does recall that there were benefits to this arrangement as well: she was given a pass to travel unguarded, and a horse of her own.

6

Ruzhnevits’s story, like the one Herling tells, could be described as a tale of moral degradation. Alternatively, it could be called a story of survival.

From the administration’s point of view, none of this was supposed to happen. In principle, men and women were not supposed to be held in camps together at all, and there are prisoners who speak of having not laid eyes on a member of the opposite sex for years and years. Nor did camp commanders particularly want women prisoners. Physically weaker, they were liable to become a drag on camp production output, as a result of which some camp administrators tried to turn them away. At one point, in February 1941, the Gulag administration even sent out a letter to the entire NKVD leadership and all camp commanders, sternly instructing them to accept convoys of women prisoners, and listing all the jobs which women could usefully do. The letter mentions light industry and textile factories; woodwork and metalwork; certain types of forestry jobs; loading and unloading freight.

7

Perhaps because of the camp commanders’ objections, the numbers of women who were actually sent to camps always remained relatively low (as did the number of women executed during the 1937–38 purge). According to the official statistics, for example, only about 13 percent of Gulag prisoners in the year 1942 were women. This went up to 30 percent in 1945, due in part to the enormous number of male prisoners drafted and sent to the front, and also to the laws forbidding workers to leave their factory—laws which led to the arrest of many young women.

8

In 1948 it was 22 percent, falling again to 17 percent in 1951 and 1952.

9

Still, even these numbers fail to reflect the true situation, as women were far more likely to be assigned to serve their sentences in the light-regime “colonies.” In the large, industrial camps of the far north, they were even fewer, their presence even rarer.

Their low numbers meant, however, that women were—like food, clothing, and other possessions—almost always in shortage. So although they might have had little value to those compiling the camp production statistics, they had another sort of value to the male prisoners, the guards, and the camp free workers. In those camps where there were more or less open contacts between male and female prisoners—or where, in practice, certain men were allowed access to women’s camps—they were frequently propositioned, accosted, and, most commonly, offered food and easy work in exchange for sex. This was not, perhaps, a feature of life unique to the Gulag. A 1999 Amnesty International report on women prisoners in the United States, for example, uncovered cases of male guards and male prisoners raping female prisoners; of male inmates bribing guards for access to women prisoners; of women being strip-searched and frisked by male guards.

10

Nevertheless, the strange social hierarchies of the Soviet camp system meant that women were tortured and humiliated to an extent unusual even for a prison system.

From the start, a woman’s fate depended greatly on her status and position within the various camp clans. Within the criminal world, women were subject to a system of elaborate rules and rituals, and received very little respect. According to Varlam Shalamov, “A third or fourth generation criminal learns contempt for women from childhood . . . woman, an inferior being, has been created only to satisfy the criminal’s animal craving, to be the butt of his crude jokes and the victim of public beatings when her thug decides to ‘whoop it up.’” Women prostitutes effectively “belonged” to leading male criminals, and could be traded or bartered, or even inherited by a brother or friend, if the man were transferred to a different camp or killed. When an exchange occurred, “usually the parties concerned do not come to blows, and the prostitute submits to sleeping with her new master. There are no

ménages à trois

in the criminal world, with two men sharing one woman. Nor is it possible for a female thief to live with a non-criminal.”

11

Women were not the only targets either. Among the professional criminals, homosexual sex appears to have been organized according to equally brutal rules. Some criminal bosses had young male homosexuals in their entourages, along with or instead of camp “wives.” Thomas Sgovio writes of one brigadier who had a male “wife”—a young man who received extra food in exchange for sexual favors.

12

It is hard to describe the rules governing male homosexuality in camps, however, because memoirists so rarely mention the subject. This may be because homosexuality remains, in Russian culture, partly taboo, and people prefer not to write about it. Male homosexuality in the camps also seems to have been largely confined to the criminal world—and criminals left few memoirs.

Nevertheless, we do know that by the 1970s and 1980s, Soviet criminals did develop extremely complicated rules of homosexual etiquette. “Passive” male homosexuals were ostracized from the rest of prison society, ate at separate tables, and did not speak to the other men.

13

Although rarely described, similar rules seem to have existed in some quarters as early as the late 1930s, when Pyotr Yakir, age fifteen, witnessed an analagous phenomenon in a cell for juvenile criminals. At first, he was shocked to hear the other boys speaking of their sexual experiences, and believed them to be embellished, but I was mistaken. One of the kids had hung on to his bread ration until evening when he asked Mashka, who had had nothing to eat all day. “Do you want a bite?”

“Yes,” Mashka replied.

“Then take your trousers down.”

It took place in a corner, into which it was difficult to see from the spy-hole, but in full view of everybody in the cell. It surprised no one and I pretended not to be surprised by it. There were many other instances while I was in that cell; it was always the same boys who played the passive partner. They were treated like pariahs, were not allowed to drink from the common cup, and were the objects of humiliation.

14