Gulag (46 page)

Often, the Muscovites were particularly powerful and organized. Leonid Trus, arrested while still a student, recalled the older Muscovites in his camp forming a tight network which left him out. Even when, on one occasion, he wanted to borrow a book from the camp library, he first had to convince the librarian, a member of this clan, that he could be trusted with it.

86

More often, however, such links were weak, providing prisoners with nothing more than people who remembered the street where they had lived or knew the school they had attended. Whereas other ethnic groups formed whole networks of support, finding places in barracks for newcomers, helping them to get easier jobs, the Russians did not. Ariadna Efron wrote that upon arrival in Turukhansk, where she was exiled with other prisoners at the end of her camp sentence, her train was met by exiles already living there:

A Jewish man took aside the Jewish women in our group, gave them bread, explained to them how to comport themselves, what to do. Then a group of Georgian women were met by a Georgian—and, after a while, there were only us Russians left, perhaps ten to fifteen people. No one came to us, offered us bread, or gave us any advice.

87

Still, there were some distinctions among the Russian inmates—distinctions based on ideology rather than ethnicity. Nina Gagen-Torn wrote that the “definite majority of women in the camps understood their fate and their suffering as an accidental misfortune, not trying to look for reasons.” For those, however, who “found for themselves some kind of explanation for what was happening, and believed in it, things were easier.”

88

Chief among those who had an explanation were the communists; those prisoners, that is, who continued to maintain their innocence, continued to profess loyalty to the Soviet Union, and continued to believe, against all of the evidence, that everyone else was a genuine enemy and should be avoided. Anna Andreeva remembered the communists searching one another out: “They found one another and clung together, they were clean, Soviet people, and thought everyone else were criminals.”

89

Susanna Pechora described seeing them upon arrival in Minlag in the early 1950s, “sitting in a corner and telling one another, ‘We are honest Soviet people, hurrah for Stalin, we aren’t guilty and our state will free us from the company of all these enemies.’”

90

Both Pechora and Irena Arginskaya, a prisoner in Kengir at the same time, recall that most of the members of this group belonged to the class of high-ranking Party members arrested in 1937 and 1938. They were mostly older; Arginskaya remembered that they were often grouped in the invalid camps, which still contained many people arrested in that earlier era. Anna Larina, the wife of the Soviet leader Nikolai Bukharin, was one of those arrested at this time who remained faithful to the Revolution at first. While still in prison, she wrote a poem commemorating the anniversary of the October Revolution:

Yet, though behind iron bars I stay, Feeling the anguish of the damned Still I celebrate this day Together with my happy land.

Today I have a new belief I will enter life again, And stride again with my Komsomol Side by side across Red Square!

Later, Larina came to regard this poem “as the ravings of a lunatic.” But at the time, she recited it to the imprisoned wives of the Old Bolsheviks, and “they were moved to tears and applause.”

91

Solzhenitsyn dedicated a chapter of

The Gulag Archipelago

to the communists, whom he referred to, not very charitably, as “Goodthinkers.” He marveled at their ability to explain away even their own arrest, torture, and incarceration as, alternately, “the very cunning work of foreign intelligence services” or “wrecking on an enormous scale” or “a plot by the local NKVD” or “treason.” Some came up with an even more magisterial explanation: “These repressions are a historical necessity for the development of our society.”

92

Later, a few of these loyalists also wrote memoirs, willingly published by the Soviet regime. Boris Dyakov’s novella,

A Story of Survival

, was published in 1964 in the journal

Oktyabr

, for example, with the following introduction: “The strength of Dyakov’s story lies in the fact that it is about genuine Soviet people, about authentic communists. In difficult conditions, they never lost their humanity, they were true to their Party ideals, they were devoted to the Motherland.” One of Dyakov’s heroes, Todorsky, describes how he helps an NKVD lieutenant write a speech on the history of the Party. On another occasion, he tells the camp security officer, Major Yakovlev, that despite his unfair conviction, he believes himself to be a true communist: “I am guilty of no crime against Soviet authority. Therefore I was, and I remain, a communist.” The major advises him to keep quiet about it: “Why shout about it? You think everyone in the camp loves communists?”

93

Indeed they did not: open communists were often suspected of working, secretly or otherwise, for the camp authorities. Writing about Dyakov, Solzhenitsyn noted that his memoir appeared to leave some things out. “

In

exchange for what

?” he asks, did security officer Sokovikov agree to secretly post Dyakov’s letters for him, bypassing the camp censor. “That kind of friendship—whence came it? ”

94

In fact, archives now show that Dyakov had been a secret police agent all of his life—code-named “Woodpecker”—and that he had continued to work as an informer in the camps.

95

The only group that surpassed the communists in their absolute faith were the Orthodox believers, as well as the members of the various Russian Protestant religious sects who were also subject to political persecution: Baptists, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Russian variations thereof. They were a particularly strong presence in the women’s camps, where they were colloquially known as

monashki

, or “nuns.” In the late 1940s, in the women’s camp in Mordovia, Anna Andreeva remembered that “the majority of the prisoners were believers,” who organized themselves so that “on holidays the Catholics would work for the Orthodox and vice versa.”

96

As previously noted, some of these sects refused to cooperate in any way with the Soviet Satan, and would neither work nor sign any official documents. Gagen-Torn describes one religious woman who was released on grounds of illness, but refused to leave the camps. “I don’t recognize your authority,” she told the guard who offered to give her the necessary documents and send her home. “Your power is illegitimate, the Anti-Christ appears on your passports . . . If I go free, you’ll arrest me again. There isn’t any reason to leave.”

97

Aino Kuusinen was in a camp with a group of women prisoners who refused to wear numbered clothing, as a result of which “the numbers were stamped on their bare flesh instead,” and they were forced to attend morning and evening roll-calls stark naked.

98

Solzhenitsyn tells the story, repeated in various forms by others, of a group of religious sectarians who were brought to Solovetsky in 1930. They rejected anything that came from the “Anti-Christ,” refusing to handle Soviet passports or money. As punishment, they were sent to a small island in the Solovetsky archipelago, where they were told they would receive food only if they agreed to sign for it. They refused. Within two months they had all starved to death. The next boat to the island, remembered one eyewitness, “found only corpses which had been picked by the birds.”

99

Even those sectarians who did work did not necessarily mix with other prisoners, and sometimes refused to speak to them at all. They would huddle together in one barrack, keeping absolutely silent, or else singing their prayers and their religious songs at the appointed times:

I sat behind the prison bars Remembering how Christ Humbly and mildly carried his heavy Cross With penitence, to Golgotha.

100

The more extreme believers tended to inspire mixed feelings on the part of other prisoners. Arginskaya, a decidedly secular prisoner, jokingly remembered that “we all loathed them,” particularly those who, for religious reasons, refused to bathe.

101

Gagen-Torn remembered other prisoners complaining about those who refused to work: “We work and they don’t! And they take bread too! ”

102

Yet in one sense, those men or women who arrived at a new camp and immediately joined a clan or a religious sect were lucky. For those who belonged to them, the criminal gangs, the more militant national groups, the true communists, and the religious sects provided instant communities, networks of support, and companionship. Most political prisoners, on the other hand, and most “ordinary” criminals—the vast majority of the Gulag’s inhabitants—did not fit in so easily with one or another of these groups. They found it more difficult to know how to live life in the camp, more difficult to cope with camp morality and the camp hierarchy. Without a strong network of contacts they would have to learn the rules of advancement by themselves.

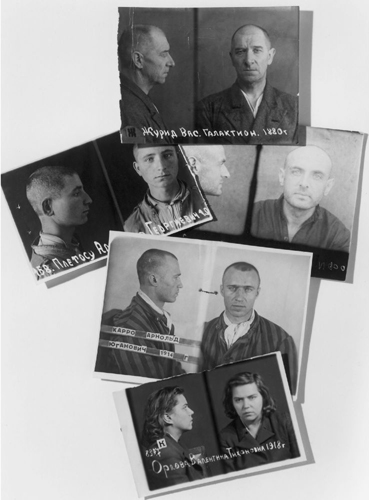

1

Vasily Zhurid; Aleksandr Petlosy; Grigori Maifet; Arnold Karro; Valentina Orlova (

top to bottom, left to right

)

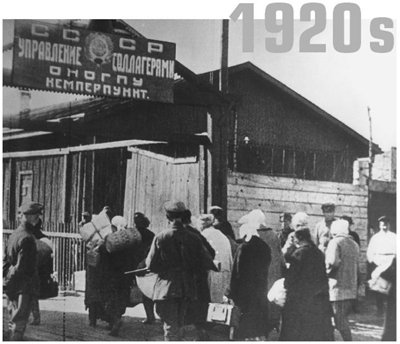

2a

Prisoners arriving at Kem, the Solovetsky transit camp

2b

Women harvesting peat, Solovetsky, 1928

3a

Maxim Gorky (center), wearing a cloth cap, coat and tie, visiting Solovetsky, 1929, with his son, daughter-in-law, and camp commanders. Sekirka church— the punishment cell—is in the background.