Gulag (34 page)

STOLOVAYA: THE DINING HALL

The vast Gulag literature contains many varied descriptions of camps, and reflects the experiences of a wide range of personalities. But one aspect of camp life remains consistent from camp to camp, from year to year, from memoir to memoir: the descriptions of the

balanda

, the soup that prisoners were served once or sometimes twice a day.

Universally, former prisoners agree that the taste of the daily or twice-daily half-liter of prison soup was revolting; its consistency was watery, and its contents were suspect. Galina Levinson wrote that it was made “from spoiled cabbage and potatoes, sometimes with a piece of pig fat, sometimes with herring heads.”

109

Barbara Armonas remembered soup made from “fish or animal lungs and a few potatoes.”

110

Leonid Sitko described the soup as “never having any meat in it at all.”

111

Another prisoner remembered soup made from dog meat, which one of his co-workers, a Frenchman, could not eat: “a man from Western countries is not always able to cross a psychological barrier, even when he is starving,” he concluded.

112

Even Lazar Kogan, the boss of Dmitlag, once complained that “Some cooks act as if they were not preparing Soviet meals, but rather pig slops. Thanks to this attitude, the food they prepare is unsuitable, and often tasteless and bland.”

113

Hunger was a powerful motivator nevertheless: the soup might have been inedible under normal circumstances, but in the camps, where most people were always hungry, prisoners ate it with relish. Nor was their hunger accidental: prisoners were kept hungry, because regulation of prisoners’ food was, after regulation of prisoners’ time and living space, the camp administration’s most important tool of control.

For that reason, the distribution of food to prisoners in camps grew into quite an elaborate science. The exact norms for particular categories of prisoners and camp workers were set in Moscow, and frequently changed. The Gulag administration constantly fine-tuned its figures, calculating and recalculating the minimum quantity of food necessary for prisoners to continue working. New orders listing ration levels were issued to camp commanders with great frequency. These ultimately became long, complex documents, written in heavy, bureaucratic language.

Typical, for example, was the Gulag administration’s order on rations, issued on October 30, 1944. The orders stipulated one “guaranteed” or basic norm for most prisoners: 550 grams of bread per day, 8 grams of sugar, and a collection of other products theoretically intended for use in the

balanda

, the midday soup, and in the kasha, or “porridge,” served for breakfast; and supper: 75 grams of buckwheat or noodles, 15 grams of meat or meat products, 55 grams of fish or fish products, 10 grams of fat, 500 grams of potato or vegetable, 15 grams of salt, and 2 grams of “surrogate tea.”

To this list of products, some notes were appended. Camp commanders were instructed to lower the bread ration of those prisoners meeting only 75 percent of the norm by 50 grams, and for those meeting only 50 percent of the norm by 100 grams. Those overfulfilling the plan, on the other hand, received an extra 50 grams of buckwheat, 25 grams of meat, and 25 grams of fish, among other things.

114

By comparison, camp guards in 1942—a much hungrier year throughout the USSR—were meant to receive 700 grams of bread, nearly a kilo of fresh vegetables, and 75 grams of meat, with special supplements for those living high above sea level.

115

Prisoners working in the sharashki during the war were even better fed, receiving, in theory, 800 grams of bread and 50 grams of meat as opposed to the 15 granted to normal prisoners. In addition, they received fifteen cigarettes per day, and matches.

116

Pregnant women, juvenile prisoners, prisoners of war, free workers, and children resident in camp nurseries received slightly better rations.

117

Some camps experimented with even finer tuning. In July 1933, Dmitlag issued an order listing different rations for prisoners who fulfilled up to 79 percent of the norm; 80 to 89 percent of the norm; 90 to 99 percent of the norm; 100 to 109 percent of the norm; 110 to 124 percent of the norm; and 125 percent and higher.

118

As one might imagine, the need to distribute these precise amounts of food to the right people in the right quantities—quantities which sometimes varied daily—required a vast bureaucracy, and many camps found it difficult to cope. They had to keep whole files full of instructions on hand, enumerating which prisoners in which situations were to receive what. Even the smallest

lagpunkts

kept copious records, listing the daily normfulfillments of each prisoner, and the amount of food due as a result. In the small

lagpunkt

of Kedrovyi Shor, for example—a collective farm division of Intlag—there were, in 1943, at least thirteen different food norms. The camp accountant—probably a prisoner—had to determine which norm each of the camp’s 1,000 inmates should receive. On long sheets of paper, he first drew out lines by hand, in pencil, and then added the names and numbers, in pen, covering page after page after page with his calculations.

119

In larger camps, the bureaucracy was even worse. The Gulag’s former chief accountant, A. S. Narinsky, has described how the administrators of one camp, engaged in building one of the far northern railway lines, hit on the idea of distributing food tickets to prisoners, in order to ensure that they received the correct rations every day. But even getting hold of tickets was difficult in a system plagued by chronic paper shortages. Unable to find a better solution, they decided to use bus tickets, which took three days to arrive. This problem “constantly threatened to disorganize the entire feeding system.”

120

Transporting food in winter to distant

lagpunkts

was also a problem, particularly for those camps without their own bakeries. “Even bread which was still warm,” writes Narinsky, “when transported in a goods car for 400 kilometers in 50 degrees of frost became so frozen that it was unusable not only for human consumption, but even for fuel.”

121

Despite the distribution of complex instructions for storing the scant vegetables and potatoes in the north during the winter, large quantities froze and became inedible. In the summer, by contrast, meat and fish went bad, and other foods spoiled. Badly managed warehouses burned to the ground, or filled with rats.

122

Many camps founded their own

kolkhoz

, or collective farm, or dairy

lagpunkts

, but these too often worked badly. One report on a camp

kolkhoz

listed, among its other problems, the lack of technically trained personnel, the lack of spare parts for the tractor, the lack of a barn for the dairy cattle, and the lack of preparation for the harvest season.

123

As a result, prisoners were almost always vitamin deficient, even when they were not actually starving, a problem the camp officials took more or less seriously. In the absence of actual vitamin tablets, many forced prisoners to drink

khvoya

, a foul-tasting brew made out of pine needles and of dubious efficacy.

124

By way of comparison, the norms for “officers of the armed forces” expressly stipulated vitamin C and dried fruit to compensate for the lack of vitamins in the regular rations. Generals and admirals were, in addition, officially able to receive cheese, caviar, canned fish, and eggs.

125

Even the very process of handing out soup, with or without vitamins, could be difficult in the cold of a far northern winter, particularly if it was being served at noon, at the work site. In 1939, a Kolyma doctor actually filed a formal complaint to the camp boss, pointing out that prisoners were being made to eat their food outdoors, and that it froze while it was being eaten.

126

Overcrowding was a problem for food distribution too: one prisoner remembered that in the

lagpunkt

adjacent to the Maldyak mine in Magadan, there was one serving window for more than 700 people.

127

Food distribution could also be disrupted by events outside the camps: during the Second World War, for example, it often ceased altogether. The worst years were 1942 and 1943, when much of the western USSR was occupied by German troops, and much of the rest of the country was preoccupied fighting them. Hunger was rife across the country—and the Gulag was not a high priority. Vladimir Petrov, a prisoner in Kolyma, recalls a period of five days without any food deliveries in his camp: “real famine set in at the mine. Five thousand men did not have a piece of bread.”

Cutlery and crockery were constantly lacking too. Petrov, again, writes

that “soup still warm when received would become covered with ice during the

period of time one man would wait for a spoon from another who had finished with

one. This probably explained why the majority of the men preferred to eat

without spoons.”

128

Another prisoner believed that she had remained alive because she “traded bread for a half-liter enamel bowl . . . If you have your own bowl, you get the first portions—and the fat is all on the top. The others have to wait until your bowl is free. You eat, then give it to another, who gives it to another . . .”

129

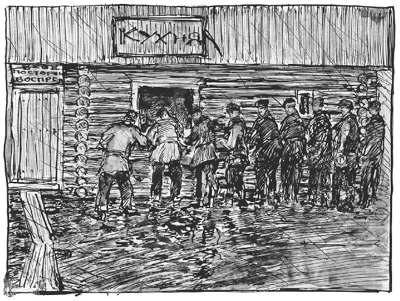

In the Camp Kitchen

: prisoners lining up for soup—a drawing by Ivan Sykahnov, Temirtau, 1935–1937

Other prisoners made their own bowls and cutlery out of wood. The small museum housed in the headquarters of the Memorial Society in Moscow displays a number of these strangely moving items.

130

As ever, the central Gulag administration was fully aware of these shortages, and occasionally tried to do something about them: the authorities at one point complimented one camp for making clever use of its leftover tin cans for precisely this purpose.

131

But even when crockery and cutlery existed, there was often no way to clean it: one Dmitlag order “categorically” forbade camp cooks from distributing food in dirty dishes.

132

For all of these reasons, the food ration regulations issued in Moscow— already calculated to the minimum level required for survival—are not a reliable guide to what prisoners actually ate. Nor do we need to rely solely on prisoners’ memoirs to know that Soviet camp inmates were very hungry. The Gulag itself conducted periodic inspections of its camps, and kept records of what prisoners were actually eating, as opposed to what they were supposed to be eating. Again, the surreal gap between the neat lists of food rations drawn up in Moscow and the inspectors’ reports is startling.

The investigation of the camp at Volgostroi in 1942, for example, noted that at one

lagpunkt

, there were eighty cases of pellagra, a disease of malnutrition: “people are dying of starvation,” the report noted bluntly. At Siblag, a large camp in western Siberia, a Soviet deputy prosecutor found that in the first quarter of 1941, food norms had been “systematically violated: meat, fish, and fats are distributed extremely rarely . . . sugar is not distributed at all.” In the Sverdlovsk region in 1942, the food in camps contained “no fats, no fish or meat, and often no vegetables.” In Vyatlag in 1942, “the food in July was poor, nearly inedible, and lacking in vitamins. This is because of the lack of fats, meat, fish, potatoes . . . all of the food is based on flour and grain products.”

133

Some prisoners, it seems, were deprived of food because the camp had not received the right deliveries. This was a permanent problem: in Kedrovyi Shor, the

lagpunkt

accountants kept a list of all food products which could be substituted for those that prisoners should have received but did not. These included not only cheese for milk, but also dried crackers for bread, wild mushrooms for meat, and wild berries for sugar.

134

It was hardly surprising that, as a result, the prisoners’ diet looked quite different from how it did on paper in Moscow. An inspection of Birlag in 1940 determined that “the entire lunch for working

zeks

consists of water, plus 130 grams of grain, and that the second course is black bread, about 100 grams. For breakfast and supper they reheat the same sort of soup.” In conversation with the camp cook, the inspector was also told that the “theoretical norms are never fulfilled,” that there were no deliveries of fish, meat, vegetables, or fats. The camp, concluded the report, “doesn’t have money to buy food products or clothing . . . and without money not one supply organization wants to cooperate.” More than 500 cases of scurvy were reported as a result.

135

Just as frequently, however, food arrived in a camp only to be stolen immediately. Thieving took place at just about every level. Usually, food was stolen while it was being prepared, by those working in the kitchen or food storage facilities. For that reason, prisoners sought out jobs which gave them access to food—cooking, dishwashing, work in storage warehouses— in order to be able to steal. Evgeniya Ginzburg was once “saved” by a job washing dishes in the men’s dining hall. Not only was she able to eat “real meat broth and excellent dumplings fried in sunflower-seed oil,” but she also found that other prisoners stood in awe of her. Speaking to her, one man’s voice trembled, “from a mixture of acute envy and humble adoration of anyone who occupied such an exalted position in life—‘where the food is!’”

136