Gulag (15 page)

The origins of this vast republic of prisons lay in one of the earliest OGPU expeditions, the Ukhtinskaya Expedition, which set out in 1929 to explore what was then an empty wilderness. By Soviet standards, the expedition was relatively well-prepared. It had a surfeit of specialists, most of whom were already prisoners in the Solovetsky system: in 1928 alone, sixty-eight mining engineers had been sent to SLON, victims of that year’s campaigns against the “wreckers” and “saboteurs” who were supposedly holding back the Soviet Union’s drive to industrialization.

7

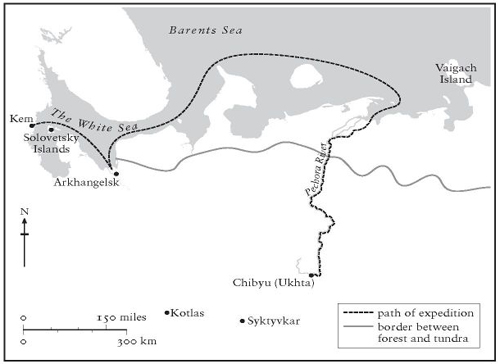

In November 1928, with mysteriously good timing, the OGPU also arrested N. Tikhonovich, a well-known geologist. After throwing him into Moscow’s Butyrka prison, however, they did not carry out an ordinary interrogation. Instead, they brought him to a planning meeting. Wasting no time on preliminaries, Tikhonovich remembered later, a group of eight people—he was not told who they were—asked him, point-blank, how to prepare an expedition to Komi. What clothes would he take if he were going? How many provisions? Which tools? Which method of transport? Tikhonovich, who had first been to the region in 1900, proposed two routes. The geologists could go by land, trekking on foot and on horseback over the mud and forest of the uninhabited taiga to the village of Syktyvkar, then the largest in the region. Alternatively, they could take the water route: from the port of Arkhangelsk in the White Sea, along the northern coast to the mouth of the Pechora River, then continuing inland on the Pechora’s tributaries. Tikhonovich recommended the latter route, pointing out that boats could carry more heavy equipment. On his recommendation, the expedition proceeded by sea. Tikhonovich, still a prisoner, became its chief geologist.

No time was wasted, and no expense was spared, for the Soviet leadership considered the expedition to be an urgent priority. In May, the Gulag administration in Moscow named two senior secret police bosses to lead the group: E. P. Skaya—the former chief of security at the Smolny Institute, Lenin’s first headquarters during the Revolution, and later chief of security at the Kremlin itself—and S. F. Sidorov, the OGPU’s top economic planner. At about the same time, the expedition bosses selected their “workforce”— 139 of the stronger, healthier prisoners in the SLON transit camp in Kem, politicals, kulaks, and criminals among them. After two more months of preparation, they were ready. On July 5, 1929, at seven o’clock in the morning, the prisoners began loading equipment on to SLON’s steamer, the

Gleb

Boky.

Less than twenty-four hours later, they set sail.

Not surprisingly, the floating expedition encountered many obstacles. Several of the guards appear to have got cold feet, and one actually ran away during a stopover in Arkhangelsk. Small groups of prisoners also managed to escape at various points along the route. When the expedition finally made it to the mouth of the Pechora River, local guides proved difficult to find. Even if paid, the indigenous Komi natives did not want anything to do with prisoners or the secret police, and they refused to help the ship navigate upstream. Nevertheless, after seven weeks the ship finally arrived. On August 21, they set up their base camp in the village of Chibyu—later to be renamed Ukhta.

After the tiring voyage, the general mood must have been exceptionally gloomy. They had traveled a long way—and where had they arrived? Chibyu offered little in the way of creature comforts. One of the prisoner specialists, a geographer named Kulevsky, remembered his first view of the place: “The heart compressed at the sight of the wild, empty landscape: the absurdly large, black, solitary watch tower, the two poor huts, the taiga and the mud . . .”

8

He would have had little time for further reflection. By late August, hints of autumn were already in the air. There was little time to spare. As soon as they arrived, the prisoners immediately began to work twelve hours a day, building their camp and their work sites. The geologists set out to find the best places to drill for oil. More specialists arrived later in the autumn. New prisoner convoys arrived too, first monthly and then weekly, throughout the 1930 “season.” By the end of the expedition’s first year, the number of prisoners had grown to nearly a thousand.

Despite the advance planning, conditions in these early days, for both prisoners and exiles, were horrendous, as they were everywhere else. Most had to live in tents, as there were no barracks. Nor were there enough winter clothes and boots, or anywhere near enough food. Flour and meat arrived in smaller quantities than had been ordered, as did medicines. The number of sick and weakened prisoners rose, as the expedition’s leaders admitted in a report they filed later. The isolation was no less difficult to bear. So far were these new camps from civilization—so far were they from roads, even, let alone railway lines—that no barbed wire was used in Komi until 1937. Escape was considered pointless.

Still, prisoners kept arriving—and supplementary expeditions continued to set out from the base camp at Ukhta. If they were successful, each one of these expeditions founded, in turn, a new base camp—a

lagpunkt—

sometimes in places that were almost impossibly remote, several days’ or weeks’ trek from Ukhta. They, in turn, founded further sub-camps, to build roads or collective farms to serve the prisoners’ needs. In this manner, camps spread like fast-growing weeds across the empty forests of Komi.

The route of the Ukhtinskaya Expedition, Komi Republic, 1929

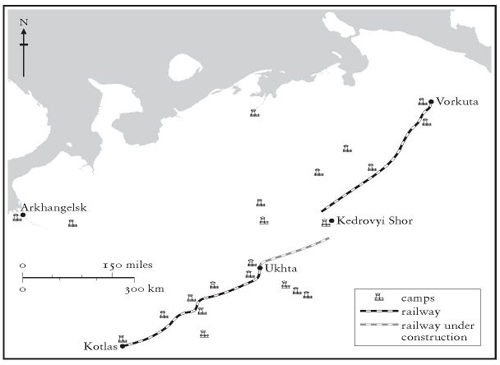

Ukhtpechlag, Komi Republic, 1937

Some of the expeditions proved to be temporary. Such was the fate of one of the first, which set out from Ukhta in the summer of 1930 for Vaigach Island, in the Arctic Sea. Earlier geological expeditions had already found lead and zinc deposits on the island, although the Vaigach Expedition, as it came to be called, was well provided with geologist prisoners as well. Some of these geologists performed in such an exemplary manner that the OGPU rewarded them: they were allowed to bring their wives and children to live with them on the island. So remote was the location that the camp commanders appear not to have worried about escape, and they allowed prisoners to walk anywhere they wished, in the company of other prisoners or free workers, without any special permissions or passes. To encourage “shock-work in the Arctic,” Matvei Berman, then the Gulag boss, granted prisoners on Vaigach Island two days off their sentence for every such day worked.

9

In 1934, however, the mine filled with water, and the OGPU moved both prisoners and equipment off the island the following year.

10

Other expeditions would prove more permanent. In 1931, a team of twenty-three set off northward from Ukhta by boat, up the inland waterways, intending to begin the excavation of an enormous coal deposit—the Vorkuta coal basin—discovered in the Arctic tundra of the northern part of Komi the previous year. As on all such expeditions, geologists led the way, prisoners manned the boats, and a small OGPU contingent commanded the operation, paddling and marching through the swarms of insects that inhabit the tundra in summer months. They spent their first nights in open fields, then somehow built a camp, survived the winter, and constructed a primitive mine the following spring: Rudnik No. 1. Using picks and shovels and wooden carts, and no mechanized equipment whatsoever, the prisoners began to dig coal. Within a mere six years, Rudnik No. 1 would grow into the city of Vorkuta and the headquarters of Vorkutlag, one of the largest and toughest camps in the entire Gulag system. By 1938, Vorkutlag contained 15,000 prisoners and had produced 188,206 tons of coal.

11

Technically, not all of the new inhabitants of Komi were prisoners. From 1929, the authorities also began to send “special exiles” to the region. At first these were almost all kulaks, who arrived with their wives and children and were expected to start living off the land. Yagoda himself had declared that the exiles were to be given “free time” in which they were to plant gardens, raise pigs, go fishing, and build their own homes: “first they will live on camp rations, then at their own cost.”

12

While all of that sounds rather rosy, in fact nearly 5,000 such exile families arrived in 1930—over 16,000 people—to find, as usual, almost nothing. There were 268 barracks built by November of that year, although at least 700 were needed. Three or four families shared each room. There was not enough food, clothing, or winter boots. The exile villages lacked baths, roads, postal service, and telephone cables.

13

Although some died, and many tried to escape—344 had attempted to escape by the end of July—the Komi exiles became a permanent adjunct to the Komi camp system. Later waves of repression brought more of them to the region, particularly Poles and Germans. Hence the local references to some of the Komi villages as “Berlin.” Exiles did not live behind barbed wire, but did the same jobs as prisoners, sometimes in the same places. In 1940, a logging camp was changed into an exile village—proof that, in a certain sense, the groups were interchangeable. Many exiles also wound up working as guards or administrators in the camps.

14

In time, this geographical growth was reflected in camp nomenclature. In 1931, the Ukhtinskaya Expedition was renamed the Ukhto-Pechorsky Corrective-Labor Camp, or Ukhtpechlag. Over the subsequent two decades, Ukhtpechlag itself would be renamed many more times—and reorganized and divided up—to reflect its changing geography, its expanding empire, and its growing bureaucracy. By the end of the decade, in fact, Ukhtpechlag would no longer be a single camp at all. Instead, it spawned a whole network of camps, two dozen in total, including: Ukhtpechlag and Ukhtizhemlag (oil and coal); Ustvymlag (forestry); Vorkuta and Inta (coal-mining); and Sevzheldorlag (railways).

15

In the course of the next several years, Ukhtpechlag and its descendants also became denser, acquiring new institutions and new buildings in accordance with their ever-expanding requirements. Needing hospitals, camp administrators built them, and introduced systems for training prisoner pharmacists and prisoner nurses. Needing food, they constructed their own collective farms, their own warehouses, and their own distribution systems. Needing electricity, they built power plants. Needing building materials, they built brick factories.

Needing educated workers, they trained the ones that they had. Much of the ex-kulak workforce turned out to be illiterate or semiliterate, which caused enormous problems when dealing with projects of relative technical sophistication. The camp’s administration therefore set up technical training schools, which required, in turn, more new buildings and new cadres: math and physics teachers, as well as “political instructors” to oversee their work.

16

By the 1940s, Vorkuta—a city built in the permafrost, where roads had to be resurfaced and pipes had to be repaired every year—had acquired a geological institute and a university, theaters, puppet theaters, swimming pools, and nurseries.

Yet if the expansion of Ukhtpechlag was not much publicized, neither was it haphazard. Without a doubt the camp’s commanders on the ground wanted their project to grow, and their prestige to grow along with it. Urgent necessity, not central planning, would have led to the creation of many new camp departments. Still, there was a neat symbiosis between the Soviet government’s needs (a place to dump its enemies) and the regions’ needs (more people to cut trees). When Moscow wrote offering to send exile settlers in 1930, for example, local leaders were delighted.

17

The camp’s fate was discussed at the highest possible levels as well. It is worth noting that in November 1932, the Politburo—with Stalin present—dedicated most of an entire meeting to a discussion of the present state and future plans of Ukhtpechlag, discussing its prospects and its supplies in surprising detail. From the meeting’s protocols, it seems as if the Politburo made all the decisions, or at least approved everything of any importance: which mines the camp should develop; which railways it should construct; how many tractors, cars, and boats it required; how many exile families it could absorb. The Politburo also allocated money for the camp’s construction: more than 26 million rubles.

18