Gallipoli (43 page)

Authors: Peter FitzSimons

He is making his way back to the line from Battalion HQ when he sees âa number of men ⦠pouring down the slope at the double'. Stopping them, he demands, âWho has instructed you to leave the Firing Line?'

Several answer at once, saying the word had come from the right that âevery man was to make his way to the beach independently and as fast as he could'.

Tricky buggers!

He tells the men, âThis is nothing but a dirty German trick. I am in charge of the Firing Line ⦠no such orders have been given.'

33

The men immediately turn on their heels and follow Major Beevor back to the line.

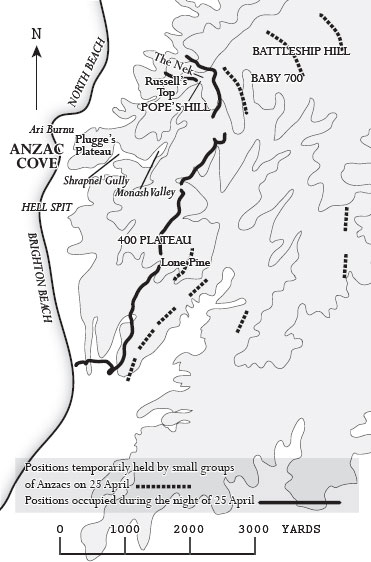

Troop positions, 25 April 1915, by Jane Macaulay

Having allowed time for the destructive forces of his decreed bombardment to take full effect (at 400 Plateau, it is reported that the dead are âalmost all torn apart by shrapnel'),

34

Lieutenant-Colonel Mustafa Kemal launches his counter-attack all along the front. â

Yürü! Yürü! Yürü!

â Forward! Forward! Forward!' The Turks advance seaward down the slopes of the Sari Bair Range at 4 pm, across the Legge Valley and towards 400 Plateau and other points along the line.

The most crucial battle on this tortured and torrid afternoon is here and now on the hill marked as Baby 700 on the Anzac maps. As it is obvious to both sides that whoever possesses the commanding heights of Chunuk Bair will in fact command the area â having the capacity to both see the positioning of the enemy and direct artillery fire upon them â enormous efforts have been made by the Allies to secure the lower hills as a stepping stone to capturing the higher.

So numerous are the Turkish troops now, so extraordinarily committed are their charges on the now devastated Anzac frontlines, the serious risk is that Mustafa Kemal will indeed succeed in sweeping the invaders into the sea by dark. As the battle rages, the casualties on both sides are devastating: hundreds of men are killed or grievously wounded with every passing hour. Should the Anzacs evacuate immediately and save as many men as they can, before Mustafa Kemal has his way?

On no fewer than five occasions this day of the landing, Baby 700 changes hands, and yet, finally, late in the afternoon, what is left of Turkey's 57th Regiment force the few surviving Australians atop Baby 700 to retreat. In the madness of all the fighting, some soldiers seem to disappear. One instant, they are there; the next, they are gone. With some, it is because they take direct hits from a shell and simply cease to exist. With others, the story is stranger. One such is Private Edgar Adams of 8th Battalion. First he is there, fighting with the best of them as the Turks charge, and then he is gone. A quick search is conducted, but no trace of him is found â¦

As the battle continues to teeter on the point of disaster for the attackers, their only consolation is, with the Turkish guns trained mostly inland, the transports and boats have been able to resume landing troops and materiel. The bulk of the New Zealanders are now beginning to arrive, including the first companies of Lieutenant-Colonel William Malone's Wellington Battalion, which begin to wade ashore from about half-past four in the afternoon.

Likely the most courageous men on the day bear no arms at all. They are the stretcher-bearers, men with âSB' marked in brassards on their arms. One stretcher-bearer who stands out for his particular bravery under fire is Jack Simpson of the 3rd Australian Field Ambulance Australian Army Medical Corps. Even though the men on either side of him as he had landed at the tail end of the 3rd Brigade were shot dead â and indeed 16 of the unit had become casualties in the boats before even landing â still Simpson had quickly got to work and begun ferrying wounded men back to the shore. And he and many others have been at it all day since.

Down at the beach, Lieutenant-Colonel Dr Percival Fenwick is hard at work attending to the ânumbers of wounded lying [at the Clearing Station] close to the cliff waiting to be sent off to the ship. Every minute the number increased ⦠Violent bursts of shrapnel swept over us, and many wounded were hit a second time. Colonel Howse ⦠was packing boats and barges with these poor chaps as fast as possible, but the beach kept filling again with appalling quickness ⦠The shrapnel never ceased â¦'

35

By late afternoon, there are no fewer than 700 of them there, waiting to be put on barges and, adding seasickness to injury, towed by steamboat to whichever ships will have them.

As hard as the steamboats towing barges are working â because with rumour of withdrawal in the air, clearing the beach is done in earnest â still they can make no headway in reducing the net number of wounded coming off the beach. Each time they return from the ships, there are a hundred more there, with further hundreds waiting to come down from the heights after nightfall, when it will be safer.

As some of the shattered remains of what had been a fine fighting force as recently as 12 hours ago comes aboard his ship,

London

, Ashmead-Bartlett can witness for himself dozens of men with bloody stumps where their arms and legs used to be, soldiers with their intestines spilling out onto the deck as they are lowered down, men screaming in agony ⦠and many, many death rattles of men mercifully breathing their last,

straining

for the blessed relief of sweet oblivion. From those still able to talk, Ashmead-Bartlett at least begins to take notes, gathering information on just what has happened.

Likely nowhere are things as grim as aboard the quickly overwhelmed hospital ship HMT

Armadale

, where the Chief Medical Officer, Dr Vivian Benjafield, has been stunned by the task his people face. With the aid of untrained privates and non-commissioned officers, the medical personnel conduct amputations, tie off arteries, suture dreadful abdominal wounds, try to stabilise those suffering from compound fractures of the skull, and all the rest. By lunchtime,

Armadale

has had 150 grievously wounded soldiers on board, and has had to rip out tables and turn the Mess into a makeshift ward. Can they cope with more?

They

have to

.

Even with the dead being quickly buried at sea, soon the ship is so lacking in space â with now 850 severely wounded men on board â that Benjafield has no choice but to refuse a boatload of severe cases, as his people simply won't be able to get to them. Many such boatloads are reduced to going from ship to ship, begging for the captains to accept their passengers into their makeshift triages.

Things are so desperate that one ship,

City of Benares

, which has just been cleared of a cargo of mules, is pressed into service, while

Lutzow

still has 160 horses on board when it is obliged to take on the wounded and âthe veterinary surgeon is said to have been the sole medical officer for her 300 patients until a naval doctor was sent to help him [the next day]'.

36

Aboard the ships, the remainder of the New Zealand and Australian Division are preparing to land, and their number includes Signaller Ellis Silas, who, in the late afternoon, is with his 16th Battalion in the bowels of their troopship receiving their final instructions from Captain Eliezer âMargy' Margolin. The captain talks of the âimpossible task' they face, of their âprobable annihilation' and yet also expresses his confidence that the 16th Battalion will meet the challenge.

As recorded by Ellis Silas, the men âjoke with each other about getting cold feet, but deep down in our hearts we know when we get to it we will not be found wanting â¦' But after Margy's speech, no one is under any illusion. âFor the last time in this world many of us stand shoulder to shoulder. As I look down the ranks of my comrades I wonder which of us are marked for the land beyond.'

37

Silas is not long in finding out, as just 30 minutes after this last address, he, as part of Colonel John Monash's 4th Brigade, is stepping ashore at Gallipoli while all the while it is âraining lead'. Though wide-eyed with horror at the spectacle of dead and dying men on the beach, he is stunned at the courage of all those survivors around him. âIt was a magnificent spectacle to see those thousands of men rushing through the hail of Death as though it was some big game â these chaps don't seem to know what fear means â in Cairo I was ashamed of them, now I am proud to be one of them though I feel a pigmy beside them.'

38

There is little time for reflection, however, as all of these last troop arrivals of the day must be rushed forward to support those in the frontlines, in the case of Silas's 16th Battalion digging in at a spot to be called Pope's Hill, where the men already there are only just holding on under severe counter-attack. There is a real fear that, despite having landed about 15,000 Anzac soldiers by this time, the Anzacs are about to be overwhelmed and an ignominious withdrawal announced.

Silas starts climbing the hills with the rest of his fellows, shocked by all of the noise, the savagery and the sheer bloodiness of this new world. Unable to find any of his fellow signallers in the confusion, he sets to on his own initiative. âNow some of the chaps are getting it â groans and screams everywhere, calls for ammunition and stretcher bearers, though how the latter are going to carry stretchers along such precipitous and sandy slopes beats me. Now commencing to take some of the dead out of the trenches; this is horrible; I wonder how long I can stand it.'

39

As the sun begins to sink just behind the purple haze of Imbros â soon to send up exquisitely beautiful streamers of gold into the sky â so the first serious artillery is landed. With a cry of âLook out! Make way!',

40

a single gun of the 4th Battery Australian Field Artillery is brought to the beach on a barge, unloaded and hitched to a team of horses. They immediately take the strain and start to pull it into position up a steep path to a knoll near the southern end of the beach, as the many wounded soldiers cheer. Even those wounded soldiers passing in a boat headed for the hospital ship muster the energy to cheer and sing out at the sight of the gun, âThey want Artillery!'

41

An attempt had been made earlier in the afternoon to emplace two field guns. But as no suitable location had been found for them in the highly precipitous country, and with rumours of re-embarkation then circulating, they were disappointingly soon re-embarked. So this gun is particularly welcome. Time to give the Turks back some of their own.

And indeed, with just its second shell, just after 6 pm, the gun appears to silence the Turkish gun on Gaba Tepe that has been devastating those on the beach all day. (Under heavy fire,

Bacchante

had had to withdraw at noon.) As was immortalised in the unit's War Diary, âA gun's flashes were observed on Gaba Tepe and engaged and no gun fired from the same place again.'

42

The silencing of this gun is a relief, but only a small one, as death continues to rain down upon the Anzacs. On this devastating day, across the Gallipoli Peninsula, thousands of soldiers, attackers and defenders alike have gone to an eternity of darkness. For those still alive, their most earnest desire is for the darkness of just this one night to descend, hopefully to offer

some

respite.