Gallipoli (46 page)

Authors: Peter FitzSimons

'ANGIN' ON, LIKE CATS TO A CURTAIN

Of course it was Hell, but you must remember we had been on that transport more or less for weeks, we were ripe for any sort of action. We could have been painting Cairo pink if we had been there, so we painted Gallipoli scarlet instead â¦

1

Private Harold Cavill

Had a darn good sleep and got up at about 6 am, and issued rations to the chaps. Then the shrapnel began and it hailed around about us and hit everything around me but myself. We deepened our sleeping place about three feet, but it was not deep enough.

2

Captain Dorian King, 3rd Battery, Australian Field Artillery

26 APRIL 1915, THE MORNING AFTER

Good God, the sheer

horror

of it all.

While on the day of the landing there had been little time to comprehend the ghastliness of what was happening all around you â because you were too busy adding to it â the sun rises this morning on a scene of such horror that those still alive to see it have the images burned into their brains forevermore.

As New Zealand journalist-turned-soldier William John Rusden Hill makes his way up a gully that had been bitterly fought over the day before, he can barely credit, or stomach, what he is seeing: âDead, nothing but dead men. New Zealanders, Maoris, Englishmen, Australians, and Turks. Hundreds upon hundreds of them, lying in all sorts of attitudes, some hardly marked, others mangled out of all hope of recognition and swarming all over â the flies.'

3

Most extraordinary is how men who have survived to see this new day, still so fresh to war, have already been hardened by the battle. As one Australian private records, âAt first the shrapnel had me shivering and the hail of bullets made me duck, but I'm all over that now. I think I hugged the earth closer than I ever hugged a girl. Now it gives me a sort of blood-curdling satisfaction to shoot at men as fast as I can; and a bayonet charge is the acme of devilish excitement.'

4

On this same morning, under heavy machine-gun fire, Colonel Fahrettin, the Chief of Staff of the Ottoman 3rd Corps, struggles his way to the top of the Third Ridge, where he knows Lieutenant-Colonel Mustafa Kemal is temporarily headquartered. And now, in a sheltered place of relative calm, here is Lieutenant-Colonel Mustafa Kemal, standing on a stream bed, just behind Scrubby Knoll on the ridge line.

Colonel Fahrettin, an old friend, is greeted warmly, and they embrace and kiss twice. The two are a study in contrasts. Mustafa Kemal is handsome, with eyes of steel blue and high cheekbones to rival an ancient Egyptian queen. Military in bearing from top to bottom, he is a man of regal posture who looks like he was

born

to lead. Colonel Fahrettin, on the other hand, with his droopy left eye and ill-defined chin, looks nothing of the kind, as highly respected an officer as he is. Both have had sleepless nights, but whereas Mustafa Kemal looks as fresh as the morning dew, Colonel Fahrettin is crumpled.

After Mustafa Kemal has stated his needs, Fahrettin asks, âWill your headquarters always be here? What is the name of this place?'

âYes,' he replies with that calm tone and sparkle in his eye that inspires good faith and confidence in his comrades. âFor the time being.' He adds with a laugh, âDoes a gully have a name?'

Colonel Fahrettin smiles and says, âYes, yes ⦠all right ⦠It could be called

Kemalyeri

[the Place of Kemal], for example?'

5

Lieutenant-Colonel Mustafa Kemal smiles back and nods.

Kemalyeri it is. They embrace once more, and Kemal watches quietly as his friend mounts his horse and begins his ride back to headquarters at Maidos. From the near distance, the combined roar of artillery and machine-gun fire is intensifying again.

Such is the way of warfare. Isolated actions are now taking place across the frontline while both sides gird themselves for another big thrust â the Turks to push the Anzacs into the sea, the Anzacs to break through at last. In an effort to do so, the first priority of the Anzac officers is to gather up the men whom Bean delicately refers to as stragglers â soldiers who had collected on the beach the previous afternoon and evening â and put them back into the line.

I have heard their number put at anything from 800 to 1000

, Bean writes in his diary, choosing his words carefully, even crossing one word out when he decides it is too inflammatory.

Many of them came down with wounded men. This is an offence in war, but few realised it at this early stage. The helping down of wounded did not really begin until about 4 or 5 pm. Then it began to reach serious fair proportions â 6 men came down with one wounded officer

.

6

For the 4000 men they have lost, the Anzacs have gained an area about a mile deep into the Peninsula, at its furthest point, and about a mile and three-quarters wide. They now continue digging their way around the perimeter, an effort soon matched by the Turks, who are also furiously hurling dirt.

(A lot of the digging on the Anzac side is for wells, as the lack of water is becoming a drastic problem â though at least

the troops had fortunately found a certain amount of water in 1 big gully which started from the sea just to the right of the beach hill

7

â while the sanitary men are digging latrines.)

At this point, just who is besieging whom is not clear. What is clear, with the arrival of more machine-guns and artillery on both sides (the Anzacs' howitzers are now, thankfully, beginning to be landed), is that anyone who tries to cross the no-man's-land between the two nascent frontlines will not last long. The Turks' position on the higher ground overlooking the Anzacs gives them an overwhelming advantage. The difficult task before the Australians and New Zealanders is to shift the Turks and their artillery off that high ground and continue their push inland to cut off the Turkish forces on the tip of the Peninsula.

The one thing that gives the Anzacs solace in the face of the unrelenting attacks is the shells from âLizzie' whistling over their heads and landing on the bonces of the Turks opposite. From 5.30 am, she has been there. True, it is only occasionally that the flat-trajectory shells find their mark on the entrenched Turks, but it is something. There is a loud explosion, an eruption of flame, smoke and dust, and then there is a crater with dismembered body parts all around. More coordinates are passed by field telephone down to GHQ on the beach, and more shells are fired, dealing old Harry to the Turks.

Watching closely, it is something that gives General Hamilton a great deal of satisfaction, at a time when there is precious little to be found elsewhere: âThe explosion of the monstrous shell darkens the rising sun; the bullets cover an acre; the enemy seems stunned for a while after each discharge. One after the other [the guns of

Queen Elizabeth

] took on the Turkish guns along Sari Bair and swept the skyline with them.'

8

And just let the Turks mass too tightly in one spot, ready to mount an attack where they could be seen by the Anzacs, and it does not take long for Lizzie â Gawd bless her cotton socks â to sort them out, too.

It is all so encouraging that the grand ship stays there until 8.30 that morning, as Hamilton would observe, âsmothering the enemy's guns whenever they dared show their snouts. By that hour our troops had regained their grip of themselves and also of the enemy, and the firing of the Turks was growing feeble.'

9

Alas, not for long, for as Lizzie moves off to Cape Helles, the Turkish artillery, having survived the ship's guns, returns in numbers. For the Anzacs, the only way to maximise their chances of survival is to dig ever deeper. And while more of their artillery is being landed and trained on the Turkish trenches, it remains the devil's own job to keep the supply of shells coming at the rate they're being fired; each shell has to be laboriously hauled up from the beach to wherever the guns are situated.

Most of the shells being carried up meet the wounded coming down, in a gully that has seen so much Anzac traffic â and therefore enemy fire â it is given the name âShrapnel Gully'.

Right in the midst of this dreadful hell of flying bullets, screaming men and shells exploding all around is Ellis Silas, half-amazed that he is still alive after so many have fallen around him. Despite the horror of it, somehow his artist's eye is entranced by the fact that still âthe birds are chirping in the clear morning air; and buzzing about from leaf to leaf, placidly going about its work, is a large bee â to think of what might be makes me weep, for fighting is continuing in all its fury'.

10

He is fatalistic about what lies ahead.

âOur signallers have been nearly all wiped out â I suppose I'll get my lead pill next. It has been now a ceaseless cry of “Stretcher bearers on the left” â they seem to be having an awful time up there â one poor fellow has just jumped out of his dug-out, frightfully wounded in the arm; I bound it up as best I could, then had to dash off with another message.'

11

Oh, those stretcher-bearers. In just the last day, they have made their reputation forevermore by their extraordinary bravery under fire. While everyone else is digging in and hugging mother earth as if their life depends upon it â because it does â the stretcher-bearers must walk bolt upright and go to where the wounded soldiers lie in no-man's-land or on the frontlines. Then they must carry them back to dressing stations or right down to the beach, before journeying back again through the same hell. Of course, these heroes are killed in droves, but still they keep going.

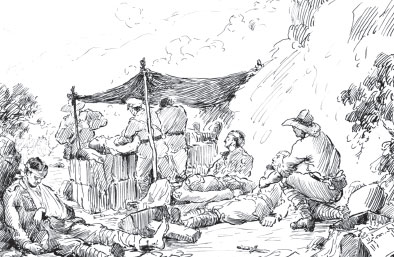

âField Dressing Station', by Ellis Silas (AWM ART90794)

âWhatever fantasies they or their families had held about them being safe behind the lines,' Ellis Silas would record, âdisappeared with the first scream of “Stretcher bearer!”'

12

Captain Gordon Carter has long since lost all his own illusions about any glory being associated with warfare, and though he had survived the previous night all right â despite the Turks launching three attacks on his position â it is touch and go now. They have again pressed forward only to be pinned down by heavy rifle fire from the front and deadly machine-gun fire from the right flank. Now he is practically sucking dirt, his arms spread wide as he flattens himself, aware that machine-gun bullets are just â2 or 3 inches over me'.

13

To this is added the shrapnel, which begins to cut into the Australian soldiers. âThis was too much for the men â they retired and I'm sorry to say a great many broke into a rabble.'

14

Nevertheless, by forging forward, Carter and another officer, together with a few men, manage to find some cover, and by âthe shouting of Cooees we managed to get most of them to return to what was really a safe position, unget at able by shells. The men dug and made themselves more secure and we got the position strengthened.'

15

At Cape Helles, the same chaotic situation reigns as the day before. Some 12,000 soldiers have been landed. They are dug in, and they are holding. The British officers on the ground are catching their collective breath rather than seizing the opportunity to press home any advantage they might hold in certain locations.

One of the biggest of Hamilton's myriad worries is Y Beach. At 9 am, he is handed a message: âWe are holding the ridge, till the wounded are embarked.'

Hamilton is stupefied. Why âtill'?

16

The Turkish main line is several miles away. Why, in accordance with the Cape Helles plan, are the troops not bearing down on the enemy?