Fringe Florida: Travels Among Mud Boggers, Furries, Ufologists, Nudists, and Other Lovers of Unconventional Lifestyles (27 page)

Authors: Lynn Waddell

Tags: #History, #Social Science, #United States, #State & Local, #South (AL; AR; FL; GA; KY; LA; MS; NC; SC; TN; VA; WV), #Cultural, #Anthropology

plants, which they believe are the root of all their problems.

Some of Florida’s religious imports are obscure even in the countries

where they originated. In Hialeah, a leader of Ifa Orisha, a South Afri-

can religion, preached the virtues of drinking giant African snail mucus

to cure medical ills and allegedly smuggled the highly invasive species

into Miami inside his suitcase. Federal and state authorities raided his

yard, seizing the snails after several of his followers claimed the snail

fluids made them sick. State wildlife officials since have had to deal

with a neighborhood giant snail epidemic.

Florida has homegrown faiths as well. A Jewish Brooklyn woman

says Jesus Christ told her to start the interfaith Kashi Ashram in Se-

bastian.

Newsweek

profiled a former heroin addict turned south Florida

reverend who runs his ministry on a biblical Etch A Sketch®. First, he

claimed he was the reincarnation of the Apostle Paul. Then he declared

himself Jesus Christ and changed his name to Jose Lois De Jesus, “The

Man Christ Jesus.” Not long afterward, he said he was the Antichrist

and got a “666” tattoo. Many of his followers, who he claims number 2

million across thirty-five countries, also wear his brand.

Florida has such a history with unusual religions that it even me-

morializes one. The defunct Koreshan community—a late 1800s com-

proof

mune that proselytized that man lived inside a hollow Earth—is now

the Koreshan State Historic Site in Estero.

The majority of Floridians are Christian—Catholic or Protestant.

Florida, particularly the northern portion, is definitely in the Bible Belt

and filled with fire-and-brimstone fundamentalists. The practices of

those mainstream faiths sometimes also take on a relatively extreme

bent.

A creationist theme park with fake dinosaurs operated in Pensacola

until the founder was hauled off to jail in 2009 for not paying taxes,

something he claimed wasn’t commanded by God’s law.

The controversial Christian minister Terry Jones, whose anti-Islamic

adi

rants caused international incidents, bases his ministry in Gainesville.

ro

His plan to burn Qurans in 2010 prompted a call from the White House

lF

asking him to stand down.

egn

As for Catholics, a pizza magnate turned remote scrubby pastures

irF

in southwest Florida into a town exclusively for the faith. Ave Maria is

complete with an elaborate cathedral, schools, a university, $300,000

241

homes, and a chain grocery store.

In the documentary

Florida:

Heaven

on

Earth

, Stetson University religion professor Phillip Lucus attributes Florida’s diversity of faiths and

practices to the state’s image as a land of dreams. But it also doesn’t

hurt to know that whatever you believe isn’t any weirder than some-

thing you read about in the local morning paper. It’s a shared delusion.

Nothing is impossible.

My journey into the fringe of Florida’s spirituality leads me to two

religious hotspots—the Cassadaga Spiritualist Camp and the Holy

Land Experience. They represent the extremes of the state’s unconven-

tional faiths, a juxtaposition of old and modern, New Age and Bible-

thumping Christianity, earthy and plastic.

While the Cassadaga Spiritualist Camp embraces tourism, at its core

it is a residential community of about fifty practicing mediums, psy-

chics, and healers. They practice a religion outside the mainstream in

a bucolic setting that is more Old Florida than the majority of Florida

churches. Founded in 1894, Cassadaga is the oldest active Spiritualist

community in the South.

Meanwhile, the biblical-themed Holy Land Experience in Orlando

could hardly be more iconic of modern Florida tourism as it’s based on

a Christian faith that, while not entirely mainstream, has thousands

more followers than Spiritualism.

proof

Conveniently, the two religious destinations are only about forty-

five minutes apart along I-4. My husband, James, and I start in Cas-

sadaga and work our way home.

yra

M

Age-Old to New Age

pu-W

Spiritualists believe in God as a higher power. Like Protestants, they

ol

don’t see a need for an intermediary for divine connection, and like

B

a

many New Agers, they don’t believe in hell in a literal sense. Rather

dn

they think hell can be a place on Earth, a sentiment with which anyone

a,s

who’s ever been stuck on I-4 for three hours between Tampa and Or-

eir

lando might agree. Where Spiritualists diverge from most conventional

ia

religions is in their belief that a person’s soul hangs around after they

F,

die and that trained mediums can communicate with them.

sti

Over the decades, Cassadaga residents have apparently communed

rip

with the dead more easily than they have with one another. The founder

s

was booted from a trustee meeting for swearing not long after the camp

34

was officially established. In modern times, a debate over finances led

1

to a scuffle and police being called to a camp meeting. Over the de-

cades, scribes from local papers have chronicled Cassadaga residents’

squabbles over medium protocols, appropriate behavior, finances, and

real estate. The purpose of this trip, however, isn’t to examine their dif-

ferences, but to learn what they share—an unconventional faith based

on the paranormal—and why so many seek their services. To that end,

an overnight stay in Cassadaga’s allegedly haunted hotel (the only lodg-

ing within miles) and a Sunday service are on the agenda. Of course, a

Spiritualist reading is a must.

Cassadaga is about a forty-five-minute drive northeast of downtown

Orlando. Modern Florida quickly gives way to cracker culture once you

leave Interstate 4. Handwritten signs advertise horses and goats for

sale. A rebel flag hangs from the front porch of a weathered farmhouse.

The land even becomes hilly.

Downtown Cassadaga is little more than a four-way stop with a

bathroom-sized post office and a couple metaphysical shops on one

side of the road and the hotel and camp-owned bookstore on the other.

To an outsider it isn’t clear where the official historic camp begins and

ends, but residents won’t hesitate to tell you. “Those are the leeches,”

one says of the shops on the post-office side of the road. By leeches,

she means non-camp-sanctioned psychics, many of whom set up shop

proof

outside the camp proper after the rise of the New Age movement in the

1980s made Spiritualism more popular.

An aura as thick as the summer humidity hangs in the air. The unset-

tling quiet and stillness are punctured only by the occasional chirping

of a blue jay or sparrow perched in the branches of oaks that drip lacy

Spanish moss.

A drive on the camp’s unmarked roads takes less than ten minutes, a

walk less than a half hour. There aren’t any camping facilities; the name

“camp” comes from the old-time tradition of religious “camp meet-

ings.” Many of the early camp residents were Spiritualist snowbirds,

staying the winter and returning north in summer.

adi

The architecture and style closely resemble early-twentieth-century

ro

Christian assembly retreats across America. At least half of the homes

lF

are that old, many Victorian. Landscaping is a collage of rural bizarre,

egn

and décor is whimsical—a St. Francis statue overlooks gaudy golden

irF

sphinxes, and a Buddha wears sunglasses and Mardi Gras beads. One

yard is planted in plastic flowers; another is edged in tiny American

441

flags. A quilt covers a window of one home; an Obama poster blocks

proof

It’s hard to get lost at the

Cassadaga Spiritualist Camp.

Photo by James Harvey.

another’s. Neon lights hang on screened porches. Hand-painted signs

identify mediums’ residences by saying “walk-ins welcome” or “by

appointment.”

Since it’s a holiday weekend, the place crawls with tourists as well as

regulars. The hotel is booked. Small, dusty parking lots overflow. Curi-

ous sightseers check out the bookstore and grab a bite in the hotel’s

Lost in Time Café, the only restaurant in town. Others move with pur-

pose. They seek closure with a deceased loved one, help finding a lost

pet, or guidance from their dead mother, God, Native American spirits,

Mother Earth, or whatever higher power holds their faith. They crave

assurance that there’s existence on the other side of life, something a

medium can address for a donation of around $120 an hour.

The camp bookstore has all the metaphysical tools and knickknacks.

Prayer beads, fairy figurines, Native American dream catchers, crys-

tals, healing rocks, and an array of books on the paranormal. As if there

were any doubt the community is a tourist attraction, the store also

sells T-shirts with the slogan “Cassadaga, Where Mayberry Meets the

Twilight Zone.”

James and I feed the tourism machine by buying tickets to a history

tour, one of several the camp offers. Christina, the clerk, says we are

the only ones signed up.

proof

Christina is getting off work and is able to share a little about her

life at the camp. She has an earthy fashion sense, elements of a bohe-

mian look that’s been around since the 1970s. Her dark hair is long and

straight with a hint of gray. A handkerchief skirt brushes her mid-calf.

She wears oval wire-frame glasses, a twinkling rhinestone in her nose,

strands of prayer beads, and loads of sterling-silver jewelry on her ears,

wrists, and fingers.

Although she’s only lived and worked in the camp about a year, she

was drawn to Cassadaga even as a child. “[My sister and I] used to beg

my mom to bring us here for our birthday,” she says.

A year ago an inexplicable gut feeling led her to a Sunday service.

adi

She met and started dating the leader of the camp’s Native American

ro

group, which practices tribal rituals for healing and general harmony.

lF

These include rain dances known as Turtle Dances, healing drum cir-

egn

cles, and wood flute music. Christina moved into a garage apartment

irF

of a camp home built for Abraham Lincoln’s carriage chauffeur, one of

the more illustrious former camp residents.

641

Christina and the leader of the tribal healing rituals broke up, but

proof

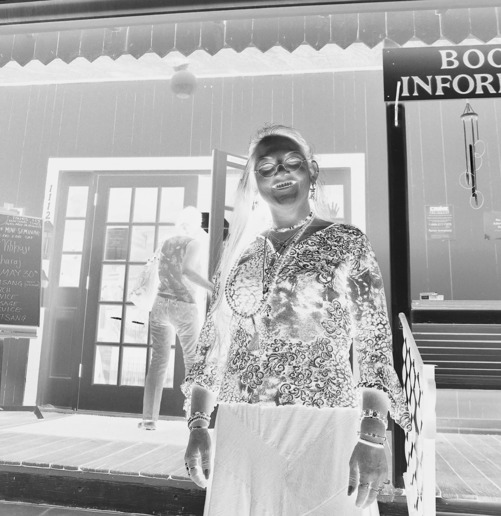

Christina, the friendly bookstore clerk. Photo by James Harvey.

yra

she believes her attraction to him was the universe’s way of getting her

Mpu

to the camp. She likes living here so much that she says she would work

-W

in the bookstore for free if she could afford it. She’s studying veterinary

ol

care at a state college and aspires to work with exotic animals, particu-

B

a

larly reptiles.

dn

Christina plans to take medium classes at the camp. She has always

a,s

been intuitive, and with training believes she could further develop