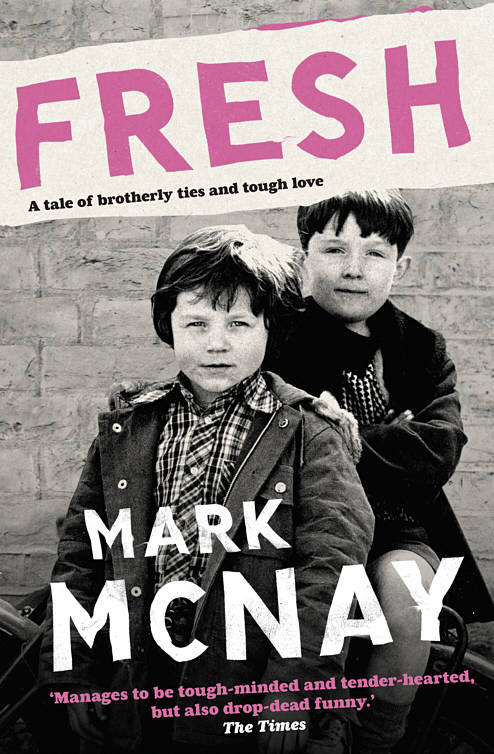

Fresh

Authors: Mark McNay

MARK M

C

NAY

For my brothers, Brian and wee Skell

The street lights were dimmed by the threat of dawn. He shivered. His wellies made a hollow scraping sound as he trudged to the bus stop. He coughed and it echoed round the pebble-dash of Cadge Road. He picked a bit of chicken feather from his overalls and let it flutter into his slipstream.

Alright wee man?

Sean turned and saw Rab and Albert coming out of the path at the side of Royston Road. He waited for them.

Alright boys?

His uncle Albert was smoking a roll-up. Rab had his hands in his pockets and swaggered like boys his age should. Sean looked at him and thought twelve years in the factory would take the swing out of his shoulders.

What are ye lookin so cocky about?

It’s Friday.

Albert had a final puff and threw his dog-end onto the pavement. He smiled.

He thinks he’s on to a promise the night.

Sean inspected his cousin.

Is that right?

Rab glanced at his dad and back to Sean.

Maybe.

Sean looked at Albert.

It’s about time he popped his cherry.

Ah’m no a virgin ya cunt.

Sean looked at Albert and smiled. Then he turned to Rab.

Alright wee man. Ah’m only kiddin with ye.

As long as ye know.

The bus stop had men round it smoking and coughing and spitting. Sean and Albert sat together on the bench. Rab stood next to the other teenagers. They stood in a circle talking about drinking and fighting and fucking. Sean listened to them for a second and turned to his uncle. Albert nodded at the youngsters. Sean gave Albert a resigned look. Sean knew he was getting old because he’d rather sit with his uncle than stand with the boys.

It wasn’t meant to be like this. Him and Maggie had some big ideas when they started seeing each other. They could have went to Canada or London, anything but get a house on Cadge Road. Maggie was lovely though. Long dark hair and blue eyes. Best-looking girl in the class. Jammy bastard they used to call him.

Albert touched Sean on the shoulder.

Fag?

Sean took the pouch and made a roll-up. He passed it back and Albert gave him a light.

Are ye for the Fiveways the night? said Albert. Sean felt gutted.

No.

What again? How no?

Ah’ve got debts to pay.

Ye must have with all that overtime ye’ve been puttin in.

Sean had a long puff on his fag.

It’s doin my fuckin head in.

So what are ye payin off?

Donna’s school trip.

From last year?

It was only six months ago.

Albert chuckled.

Aye time flies when yer old.

Albert smiled.

As long as she enjoyed herself.

Aye she did. But as soon as she got back all Ah heard was Christmas this and Christmas that.

Aye well that’s weans for ye.

Innit?

They’re dear son but worth it in the long run.

Sean looked at Albert.

Ah fuckin hope so.

Well look at how you turned out. Ye were well worth it.

Thanks Uncle Albert.

And look at our Rab. He’ll be alright as well.

Aye but look at our Archie.

Albert shook his head.

There’s always one’ll turn out rotten.

Ah hope it isnay Donna.

Albert grabbed Sean’s knee.

No she’s a good lassie. And she’s got you and Maggie as examples. She’ll be alright.

Ah fuckin hope so.

Ah know what ye need. A wee bit of fun. Take yer mind off all that serious shit that’s weighin ye down.

Tell me about it.

So c’mon out for a pint the night.

Ah cannay afford it.

Ye can surely afford one pint.

Sean felt really gutted.

Ah wish Ah could but Ah cannay.

Albert nodded and called to Rab.

D’ye hear that?

What?

Yer cousin’s no comin for a pint the night.

Rab gave Sean a pitying look.

That’s what marriage does to ye.

Sean stared at the shops across the street from the bus shelter. Albert slapped him on the leg.

Ah don’t know how ye do it. Ah’m chokin for a pint now.

Sean smacked his lips.

Tell me about it.

Ah well only ten hours to go eh?

Sean felt miserable.

More like six months.

What are ye talkin about?

That’s how long Ah’ll be payin this fuckin debt.

How, who d’ye owe?

Sean nearly told but he never. Albert put his hand on his shoulder.

Don’t worry young fella, Ah’ll buy ye one in the Saracen at lunchtime.

A double-decker appeared at the end of the street. Albert stood up and shouldered his satchel. The younger men dropped their cigarettes and stood on them. They jostled to get on first. Sean got on last, said cheers pal to the driver, and went upstairs to sit with Albert at the front. They didn’t say much, just looked out the front window at gangs of workers readying themselves as they approached a stop. The doors hissed open and it got louder as the bus filled up. Before long they were on the dual-carriageway.

The lights up the middle of the carriageway flashed past and made Albert look like someone out of an old film. Then they were out of the city and the lights stopped. They were flying in the dark. The bus slowed and indicated and turned. It rolled up a lane pushing Sean and Albert together then pulling them apart. The engine whimpered as it climbed the gears after every curve. Occasional overhanging branches would clip the side of the bus. Sometimes, through gaps in the trees, Sean would catch a glimpse of the factory, each image larger than the last. Slowly it climbed out of the dark and they were beside it, intimidated. From the top deck it looked like a prison, or a Ministry of Defence establishment. Barbed wire and searchlights and a chimney pumping smoke into the sky. The whine and whirr of machinery and no dawn chorus. The roar of buses coming from all directions. Red buses from the east and orange buses from the west.

Security guards watched as the workers were disgorged from the buses and crowded round the clock shed. Some men pushed forward as if they were eager

to get in the factory and on with their work. Sean hung back. He could smell the meat and fat of a million dead chickens. The longer he could stay away from it the better. The crowd started to thin and Sean was pulled through with the stragglers. He nodded to the security guard, punched his card through the clock, and he was a prisoner of the factory. He followed the others to the golden light coming through the door of the building.

Sean walked through the wet corridors towards the cloakroom. On the way he passed mates who’d just finished the night shift. They were smiling and the odd one would wink and nod. Sean tried to smile back but couldn’t manage more than a grimace. When he got to the cloakroom, he hung his bag on his peg and went to the toilets with Albert for a smoke.

A white cap was in the toilet combing his hair in the mirror. He carefully put on his hairnet.

Who are ye dressin up for? said Sean to the white cap.

The boy put on his cap.

Nobody, he said.

How long ye been here?

Nine weeks.

Blue cap next week then eh?

The boy looked proud.

Aye.

Albert put his hands in his pockets.

It’s no everybody that can stick this shite out for ten weeks.

Ah didnay think Ah’d do it.

Where are ye workin? said Sean.

Portions.

D’ye hear that Albert? Portions.

Albert nodded.

What, for nine weeks? said Sean.

The boy nodded.

Albert and Sean nodded. Impressed.

Yer more of a man than me son.

Albert pulled his cap firmly onto his head.

So how come George put ye in Portions?

Who’s George?

The foreman.

Ah thought his name was Malcolm.

It is. Every cunt calls him George but.

The white cap had a final adjustment, straightened his overalls and left the toilet.

Imagine that, nine weeks in Portions. Poor wee cunt, said Sean.

He cannay have a sense of smell.

Sean shuddered. Albert had a draw on his fag and leaned against the wall.

So when are we expectin Archie?

Sean scratched his head and frowned.

It’s just over six months to go. Ah think.

D’ye no know?

Aye. Ah got a letter off him at Christmas. He’s gettin out in July. But ye know what he’s like. He’ll probably have a fight with a screw the day before and end up in there for another six months. Albert laughed.

Aye maybe. But ye’ll be pleased to see him anyway.

Tryin to be funny?

Albert laughed. Sean didn’t. Albert flicked his ash on the floor.

Where will he be stayin when he gets out?

Sean laughed and nodded.

So he’ll no be stayin round yours?

What, after the last time? Yer auntie Jessie would kill me if Ah even mentioned his name, never mind ask if he could stay.

Aye, Maggie’s the same.

Has he sorted out the drugs?

Ah fuckin hope so. Ah couldnay live through that madness again. Right come on. We better move.

Albert looked at his watch.

Aye. It’s ten past already.

They dropped their butts into the urinal with the ‘Please do not drop your cigarette ends into the urinals’ sign above it, adjusted their blue caps in the mirror, and left the toilet. As they walked into the corridor Sean pulled his gloves on. They got to the double doors at the bottom of the corridor and pushed through them into the expanse that was Fresh.

Sean blinked as his eyes got used to the light. It could have been an aircraft hanger it was so big in there. Lines of chickens looped and crossed below the roof like they were on a giant roller coaster taking them for a fun day out. There were five conveyor belts arranged on the floor where the lines dropped chickens at one end, and women with hats and hairnets hovered above the belts waiting to truss them. Sean and Albert walked through Fresh till they came to a raised section at the end called the Junction. Here the chickens were sorted into those

that went to Fresh and those that went to Frozen. The chickens destined for Fresh were sorted by weight and sent to the conveyor belts and packed ready to be sold up and down the country.

Fresh chickens to be sold in butchers and supermarkets for the ease of the purchasing public. Fresh chickens you assume have been killed recently. You picture a redbrick farmyard with purple foxgloves growing in a corner. The healthy smell of shite. An old 1950s tractor quietly rusting on flat tyres, only useful to the robins that nest under the seat. The farmer’s wife comes out of the door, pulls a chicken from the ground it was idly pecking, and twists its neck with her fat powerful hands. She sits on a stool, places the quivering bird on her lap, and plucks it while it’s warm. She sings a song of somebody’s lover lost in a foreign war. She stuffs hand-stitched pillows with the feathers and sells them on the local market on a Wednesday afternoon. The plucked and dressed chicken is trussed ready to be hung that afternoon in the butcher’s and you walk in and buy a bird whose pulse has barely died in its throat.

The fresh chickens Sean handles are driven to the factory in shoebox-sized containers packed on the trailer of an articulated truck. The driver flicks a roll-up butt out of the window and calls for Rab, who sidles out of his hut and guides the lorry into the loading bay. Strong forearms reach into the shoeboxes and drag their prey into the artificial light and hang them by the ankles on a hook. They fly along, upside down, flapping their wings, trying to escape, shitting down their chests,

squawking and pecking at their mates. The hooks drag them into a tank of water where an electric current stops their hearts moments before rubber wheels grind the feathers from their skin.

By the time they reach Sean they’ve been eviscerated and beheaded and spent time in a refrigerated still-room where they remain until they cool. They appear from a hole in the wall next to Sean’s station and a computer decides whether to drop them or not onto the conveyor belt that flanks the wall. There is a rhythm to the line. Bum-titty-bum-titty-bum-titty.

Sean’s breath was smoke-like in the cool air. He was bored. He tried to blow smoke rings but all he got was puffs of steam. He pressed his hand into the conveyor belt to see if he could slow it down, to feel it struggle over the rollers, to change the tone of the machine. He pushed his finger back and forth over the belt to make a flowing pattern in the grease. He spat a green oyster onto the belt and watched it disappear into the distance. He stamped his feet to keep them warm.

*

Ah could hardly keep my eyes open. Every five minutes the teacher would shout O’Grady and Ah would twitch from the window back to the blackboard. About halfway into the lesson the head pushed his face round the door and asked her if he could have a word with me. Ah shat myself coz Ah thought Ah was nabbed for writin he was a wanker on the toilet door. He gave me a right

funny look when Ah came into the corridor and Ah nearly telt him how sorry Ah was, but as we walked towards his office Ah saw Archie waitin outside.

We went in and stood across from his desk. He sat down and looked at us. Then he telt us we’d have to be grown up about what he was goin to say. We looked at each other and back at him and nodded. Our ma had been ran down by a coal lorry on the Petershill Road. She was in the Royal Infirmary and her condition was grave. He got up and took us into his typist’s office. She gave us a sweetie each and we sat down and waited while the head tried to get our uncle. Archie picked a massive snotter out his nose and showed me it before he wiped it under his chair.

About half an hour later my uncle Albert came into the school and took us round to his. He said the hospital was no place for weans and the best place for us was with our auntie Jessie. So we sat at the kitchen table eatin cakes and tea and he went to the hospital to visit my ma. By the time he got home that night we were in our beds. He woke us up to tell us our ma had took a turn for the worse. We didnay know what to say. Archie looked at me for a while then he turned his head and went back to sleep. Well Ah thought he did but years later he telt me he waited till he heard my breathin go, then he fell asleep himself.