Founding Myths (36 page)

Authors: Ray Raphael

Today, elementary, middle-school, and secondary texts still disregard the international context, and only a handful of college texts do better. In my survey of twenty-three college texts published since 2009, only five discuss the global sweep of Britain's entanglements that informed its decision to give up the fight for its thirteen rebellious colonies in America.

42

Of the remaining eighteen, three discuss British concerns in the West Indies but nowhere else,

43

and the other fifteen remain silentâno Gibraltar, Minorca, English Channel, Cape of Good Hope, India, or the East or West Indies.

44

Some of these do mention that Britain still had many troops stationed nearby; some discuss briefly the political debates in Parliament; a few even observe, “The British could have fought on.”

45

But why did they

not

fight on, if they had the resources to do so? This is the obvious next question, and it would lead to an investigation of Britain's defense of a global empire and how this affected its policy with respect to America. But these texts don't go there.

This is surprising. For a decade now, Colonial and Revolutionary Era academics have been exploring and dissecting what they call “the Atlantic World”: the cultural, social, political, economic, and military interplay among peoples and governments of Europe, Africa, and the Americas. Yet even this has not significantly broadened the narrow parameters in which we tell the Yorktown story, not only for younger

students but at the college level as well.

46

One recent college text is subtitled

U.S. History in a Global Context

, but here is all it says about the impact of Yorktown: “When British prime minister Lord North heard the news of Yorktown, he reportedly exclaimed, âOh God! It's all over!' The British government decided to pursue peace negotiations.” So ended “the final phase of the Revolutionary War.”

47

Another recent college text, sophisticated in other respects, announces proudly, “The

Continental Army

had managed the impossible.

It

had defeated

the British

army and won the colonies' independence” (emphases added)âno mention of help from the French fleet, French army, or French finances, and acknowledgment of only a single British army, Cornwallis's.

48

It's a simple tale and still the one we still prefer: by besting Great Britain, our nation shaped its own destiny. Americans have always done their best to avoid European entanglements, and this applies to the telling of history as well as to history itself.

Â

“We said, The whole west, clear to the Mississippi, is ours; we fought for it; we took it; we hoisted our flag over its forts, and

we mean to keep it.

We did keep it.”

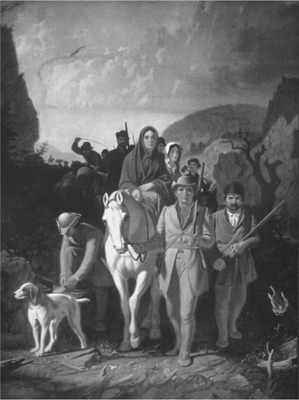

Daniel Boone Escorting Settlers through the Cumberland Gap.

Detail of painting by George Caleb Bingham, 1851â1852.

T

he American Revolution, with its happy ending, set us on our path: first a Constitution, then expansion across the continent, and finally the ascendancy to international prominence. But the story ended happily for only some. For others, the Revolutionary War signaled a loss, not a gain, of popular sovereignty. When we tell the story of the American Revolution from the standpoint of those who lost their land and their sovereign status, it takes on an entirely different aspect.

In 1958 two of the nation's most prominent historians, Henry Steele Commager and Richard B. Morris, concluded their 1,300-page compilation of primary sources for the American Revolution on a bright, optimistic note:

The American Revolution . . . did little lasting damage, and left few lasting scars. Population increased throughout the war; the movement in the West was scarcely interrupted; and within a few years of peace, the new nation was bursting with prosperity and buoyant with hope.

1

This view prevailed for two centuries. The Revolutionary War, by freeing white Americans from their shackles to the east, allowed them to lookâand moveâto the West. The rest, as they say, is history: the United States grew and thrived as it stretched across the North American continent.

We like to think of the Revolution as a war for independence. It was that, but it was simultaneously something very different: a war of conquest. Commager and Morris were partially correctâthe Revolution did promote westward expansionâbut the march of white settlers across the Appalachians did not leave all Americans “buoyant with hope.” For many indigenous people, it signaled the end, not the beginning, of independence.

The American Revolution was by far the largest “Indian war” in our nation's history. Other conflicts between Euro-Americans and Native Americans involved only a handful of Indian nations at a time, or even just a single oneâbut all nations east of the Mississippi River were directly involved in this war. Most fought actively on one side or the other; more sided with the British, but some, particularly those east of the Appalachians, thought they would gain by joining the rebels. Before and during the Revolution, Indian played off one set of whites against the other as they sought to maintain their own lands. Afterward, with the power of competing European nations on the wane and the fledgling United States tilting westward, their options became more limited: resist at all costs; retreat to the West, where other native people lived; or negotiate a surrender as best they could.

DIVIDE AND CONQUER

According to one recent high-school textbook, “Native Americans remained on the fringes of the Revolution.”

2

What constitutes a “fringe,” however, depends on one's vantage point. The Revolutionary War looks very different if we stand on Indian lands and look east.

3

Narratives told from the perspective of the Iroquois or Delaware,

Cherokee or Shawnee bear little resemblance to those most Americans have incorporated, without question, into our national narrative.

Iroquois

. Not all Iroquois were of one mind about the Revolutionary War. Both British agents and American patriots courted the Iroquois, the British using presents, the Americans veiled threats. Reasoning that American expansion posed a greater threat to their own interests, four of the six nationsâSenecas, Cayugas, Onondagas, and Mohawksâcast their lots with Britain. Influenced by a missionary named Samuel Kirkland, the other two nationsâOneidas and Tuscarorasâallied with the Americans.

4

In 1777 the grand council fire for the League of Six Nations was extinguished. Instead of coming together, Iroquois fought each other as well as their white foes. On August 6 at Oriskany, New York, several hundred Seneca, Cayuga, and Mohawk warriors joined with British rangers and loyalist volunteers to ambush patriot militiamen and their Oneida allies. Angry that their traditional allies had fought against them, Senecas attacked an Oneida settlement, and the Oneidas, in turn, plundered nearby Mohawks. A civil war among whites had become a civil war among Native people.

Pro-British Iroquois were far more numerous than their pro-American counterparts, and they figured more prominently in the war. In 1778 they staged numerous raids on white settlements, most memorably at Wyoming Valley and Cherry Valley. The following year, Congress responded by authorizing a force of some four thousand soldiers, commanded by General John Sullivan, to conduct a scorched-earth campaign against Indian villages. On July 4, 1779, Sullivan's officers offered a toast: “Civilization or death to all American Savages.”

5

Then, for the remainder of the summer, they burned every village, chopped down every fruit tree, and confiscated every domesticated plant they could find. In the name of civilization, they tried to wipe out the developed civil society of people they called savages. At the end of the campaign, Sullivan reported triumphantly to Congress:

The number of towns destroyed by this army amounted to 40 besides scattering houses. The quantity of corn destroyed, at a moderate computation, must have amounted to 160,000 bushels, with a vast quantity of vegetables of every kind. Every creek and river has been traced, and the whole country explored in search of Indians settlements, and I am well persuaded that, except one town situated near the Allegana, about 50 miles from Chinesee there is not a single town left in the country of the Five nations.

6

The Sullivan campaign, which was followed by the “Hard Winter” of 1779â1780âthe coldest on record for the eastern United Statesâcreated great hardships among the Iroquois people. (For more on the “Hard Winter,” see

chapter 5

.) It did not, however, terminate Iroquois resistance. The following summer, more than 800 warriors staged raids in the Mohawk Valley, killed or captured 330 white Americans, and destroyed six forts and over 700 houses and farms. Senecas, Cayugas, Onondagas, and Mohawks also forced Oneidas and Tuscaroras off their lands, causing them to seek refuge on the outskirts of white settlements.

The war continued in 1781, with angry Iroquois warriors continuing their raids on whites who tried to occupy their lands. When Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown, the Iroquois were still fighting, but they couldn't continue forever without British support. In 1782 that support was withdrawn, and in the Treaty of Paris the following year, Britain recognized United States sovereignty not only in the thirteen rebellious colonies but over the trans-Appalachian region as well, land which was still owned by the Iroquois and other Indian nations. Indians who had fought by the side of the British felt deceived and forsaken. Meanwhile, Euro-Americans felt entitled to settle land that Native Americans regarded as their own.

Delaware and Shawnee

. The fate of other Indian nations paralleled that of the Iroquois: the Revolution caused internal divisions, while the termination of the war triggered an onslaught of white incursions.

Initially, chiefs from the Delaware and Shawnee pledged friendship with American patriots, hoping to work out some sort of accommodation with whites who bordered on their lands. Patriot officials offered these people assurances of support and protection, and they even suggested they would allow friendly Indians “to form a state whereof the Delaware nation shall be the head, and have a representation in Congress”âone of the most disingenuous promises in the history of white-Indian relations.

7

Patriots never did come through with any significant support, and white settlers continued to harass rather than protect indigenous people, friendly or otherwise, whom they encountered. After Indian-hating frontiersmen murdered four friendly Shawnee who were being held as hostages, the rest of the Shawnee joined with their militant neighborsâthe Mingo, Miami, Wyandot, Chippewa, Ottawa, and Kickapooâin support of Britain.

8

American acts of aggression alienated the Delaware as well. When white Americans invaded their land and burned their villages, most of the Delaware joined the resistance. A few Christian converts tried to remain out of the fray, but this proved impossible. On March 8, 1782, volunteers from the Pennsylvania militia massacred ninety-six men, women, and childrenânone of whom were warriorsâat the Gnadenhutten mission. As justification for their deeds, the militiamen alleged that their victims had given aid to the British by harboring enemy warriors. This was the crude underbelly of the American Revolution in Indian country.

Cherokee

. To the south, the Cherokees waged their own war for independence during the (white) American War for Independence. When Henry Stuart, a British agent, visited the Cherokees early in 1776, he found them in heated debate over how to deal with the advance of Virginians and Carolinians onto their lands. Young warriors argued for immediate resistance: it was “better to die like men than to dwindle away by inches,” they argued. Cherokee elders, on the other hand, favored caution. The young hawks were “idle young fellows” who should not be listened to, they told Stuart. Warriors, on the other

hand, told Stuart that their elders were “old men who were too old to hunt.”

9

The threat to Native lands was producing serious stress within Cherokee society.

The warriors prevailed. In the summer of 1776 angry young Cherokees staged numerous raids on frontier white settlements, but their timing could not have been worse. Patriots had just repelled a British attack on Charleston, and since there was no other threat in the region, rebels from the four southernmost states were free to vent their rage on the Cherokee. Six thousand armed men, having trained and mobilized for war against the British, marched against Indians instead. David Ramsay, a South Carolina patriot, explained how the campaign against the Cherokee was used as a training ground for the Revolutionary War: