Founding Myths (16 page)

Authors: Ray Raphael

In this particular instance, Joseph Martin and his compatriots chose to act forcibly. “We had borne as long as human nature could endure, and to bear longer we considered folly,” Martin continued. One day, while on parade, the privates began “growling like soreheaded

dogs . . . snapping at the officers, and acting contrary to their orders.” This led to a series of events sometimes labeled the “mutiny in the Connecticut line.” Technically, the soldiers' behavior was mutinous, for privates did challenge the authority of officers; at one point, they even held bayonets to the chests of those in command. But the soldiers were not trying to seize power; they only wanted to gain some respect and a corresponding increase in rations. They did what they had to do, no moreâand they achieved results: “Our stir did us some good in the end,” Martin reported, “for we had provisions directly after.”

19

A TALE OF TWO WINTERS

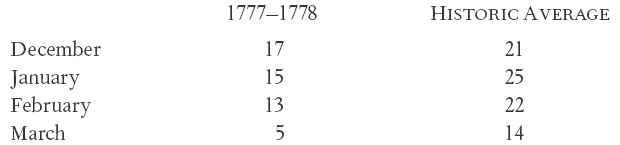

The winter of 1777â1778 was not “one of the cruelest winters in our country's history.” We have no record of daily temperatures at Valley Forge, but in nearby Philadelphia, only seventeen miles away, temperatures ran slightly above the historic average (see table). On more than half the winter mornings, there was no frost. Soldiers had to endure only one extended, hard freezeâfrom December 29 to December 31âand the thermometer dropped below double digits, briefly, only twice. Some snow did fall, but there were no memorable blizzards. Snowfall was “moderate, not heavy,” according to weather historian David Ludlum. “On the basis of cold statistics,” writes Ludlum, “the winter of 1777â1778 was not a severe one.”

20

Days with Low Temperature Below FreezingâPhiladelphia

21

Ironically, soldiers in the Continental Army did have to endure a particularly cruel winterâbut it wasn't during their camp at Valley

Forge. While camped at Morristown, New Jersey, in 1779â1780, they encountered what Ludlum concludes was “the severest season in all American history.”

22

In Philadelphia, the

high

temperature for the day rose above freezing only once during the month of January.

23

On January 20 Timothy Matlack wrote to Joseph Reed from Philadelphia: “The ink now freezes in my pen within five feet of the fire in my parlour, at 4 o'clock in the afternoon.”

24

In New York, a thermometer at British headquarters dropped to -16 degrees Fahrenheit; the lowest official reading since that time has been â15.

25

In Hartford, a daily thermometer reading revealed that January 1780 was the coldest calendar month in recorded history. On twenty-one days, the temperature dropped below 10 degrees Fahrenheit; between January 19 and January 31, subzero temperatures were recorded on nine different days, bottoming out at â22.

26

With temperatures this low, and the cold lasting for such an extended period of time, rivers and bays froze hard. In New York, the Hudson and East Rivers turned to ice. So did New York Harbor, much of Long Island Sound, and some of the ocean itself. To the south, the Delaware River froze, as did large portions of the Chesapeake Bay. In Virginia, the York and James Rivers became solid. As far south as North Carolina, Albemarle Sound froze over. According to David Ludlum, nothing like this had ever happened since the arrival of Europeans, and it has yet to happen again:

During one winter only in recorded American meteorological history have

all

the saltwater inlets, harbors, and sounds of the Atlantic coastal plain, from North Carolina northeastward, frozen over and remained closed to navigation for a period of a full month and more. This occurred during what has ever been called “The Hard Winter of 1780,” a crucial period during the war when General Washington's poorly housed, ill-clad, and under-nourished American troops at Morristown in the north Jersey hills were keeping a watchful eye on the British army

much more comfortably quartered in New York City some 20 miles distant.

27

For one winter only, frozen bays and rivers became new roadways. Rebel deserters walked across the Hudson, from New Jersey to British-controlled New York. Hessian deserters from the British army crossed Long Island Sound on foot to rebel-controlled Connecticut. The British carried firewood on sleighs across the Hudson River from New Jersey to Manhattan. They also sent sleighs laden with provisions from Manhattan to Staten Island, and they even rolled cannons across the ice; meanwhile, a detachment of British cavalry rode their horses across New York Harbor in the other direction. Sleighs traversed the Chesapeake from Baltimore to Annapolis. Had Washington decided to make his famous crossing of the Delaware during “The Hard Winter” instead of three years earlier, he could have dispensed with his boatsâthe troops would simply have marched across the frozen waters.

28

Along with cold and ice came the snow. The first major fall in Morristown arrived on December 18, 1779, and the ground remained covered for three months afterward. In late December and early January, a series of violent storms swept through the entire Northeast. On December 28â29, the wind toppled several houses in New York City. In Morristown, several feet of snow fell during the first week of January. Joseph Plumb Martin recalled the effects of the storm on the soldiers:

The winter of 1779 and '80 was very severe; it has been denominated “the hard winter,” and hard it was to the army in particular, in more respects than one. The period of the revolution has repeatedly been styled “the times that tried men's souls.” I often found that those times not only tried men's souls, but their bodies too; I know they did mine, and that effectually. . . .

At one time it snowed the greater part of four days

successively, and there fell nearly as many feet deep of snow, and here was the keystone of the arch of starvation. We were absolutely, literally starved. I do solemnly declare that I did not put a single morsel of victuals into my mouth for four days and as many nights, except a little black birch bark which I gnawed off a stick of wood, if that can be called victuals. I saw several of the men roast their old shoes and eat them, and I was afterwards informed by one of the officers' waiters, that some of the officers killed and ate a favorite little dog that belonged to one of them.âIf this was not “suffering” I request to be informed what can pass under that name; if “suffering” like this did not “try men's souls,” I confess that I do not know what could.

29

As privates struggled to stay alive, officers worried about the impact on their army. On January 5, 1780, General Nathanael Greene wrote from Morristown: “Here we are surrounded with Snow banks, and it is well we are, for if it was good traveling, I believe the Soldiers would take up their packs and march, they having been without provision two or three days.”

30

The following day, Greene's worst fears were almost realized: “The Army is upon the eve of disbanding for want of Provisions,” he reported. On January 8 Ebenezer Huntington reported, “the Snow is very deep & the Coldest Weather I ever experienced for three weeks altogether. Men almost naked & what is still worst almost Starved.”

31

Huntington, at that point, was unaware that the coldest weather was yet to come.

That same dayâJanuary 8, 1780âWashington himself offered a very bleak assessment: “The present situation of the Army with respect to provisions is the most distressing of any we have experienced since the beginning of the War”âand that included the winter spent at Valley Forge.

32

Johann de Kalb, who served as an officer under Washington, stated definitively: “Those who have only been in Valley Forge and Middlebrook during the last two winters, but have not tasted the cruelties of this one, know not what it is to suffer.”

33

For all

those who experienced both winters, there could be no doubt: Morristown was by far the worst.

Hardships continued. Since the snowpack hindered the shipment of supplies, soldiers had to face much of the winter cold and hungry. How long could they endure? On February 10 General Greene once again reported: “Our Army has been upon the point of disbanding for want of provisions.”

34

Finally, in mid-March, the weather warmed and the snow melted. Supplies arrived, and the worst was over. On March 18 Washington summed up the experience in a letter to General Lafayette: “The oldest people now living in this Country do not remember so hard a Winter as the one we are now emerging from. In a word, the severity of the frost exceeded anything of the kind that had ever been experienced in this climate before.”

35

For the soldiers, it had never been worse than at Morristown. Yet the Continental Army made it through intact. According to those on the ground at the time, not those who would tell the story generations later, Morristown was truly the low point of the warâthe real-life “Valley Forge.”

Why, then, do we make such a big deal of “The Winter at Valley Forge,” while the “Hard Winter” at Morristown is nearly forgotten? Revolutionary soldiers, scantily clad and poorly fed, had to brave the harshest weather in at least four hundred years; why is this not a part of our standard histories?

The answer, in a nutshell, is that Valley Forge better fits the story we wish to tell, while Morristown is something of an embarrassment. At Valley Forge, the story goes, soldiers suffered quietly and patiently. They remained true to their leader. At Morristown, on the other hand, they mutiniedâand this is not in line with the “suffering soldiers” motif.

As a story, Morristown doesn't work for several other reasons as well. First of all, soldiers in the Continental Army camped there during four different winters, and this is much too confusing.

36

The “Hard Winter” was the second of these. The following winter, on

January 1, 1781, the Pennsylvania line staged the largest and most successful mutiny of the Revolutionary War. Although this did not take place during the winter of 1779â1780, any mention of Morristown would necessitate at least a nod to this mutiny, which many narrative accounts conveniently leave out. The New Jersey Brigade also camped at Morristown during that third winter, and they too had just mutinied; this uprising was unsuccessful, culminating with the execution of several mutineers. To include all this would undermine a central feature of the “suffering soldier” lesson: clearly, these patriots had not endured their plight in silence.

Furthermore, to tell the complete Morristown saga would reveal that the soldiers' hardships continued throughout the war, virtually unabated. Soldiers in the Continental Army never did receive the help they needed or the respect they deserved. To admit this would make the civilian population look bad. Why didn't other patriots come to the aid of those who did the fighting?

The story of Valley Forge, on the other hand, tells us what we want to hear. Supposedly, soldiers learned to behave themselves when Baron von Steuben whipped them into shape. There were no major uprisings. The troops were allegedly obedient and well behaved. They remained faithful to Washington when his command was challenged by intrigue. All this looks good.

Also, Valley Forge and the American victory at Saratoga happened in close succession. From the storytelling point of view, this works well. Valley Forge was the “low point,” and Saratoga the “turning point,” of the Revolutionary War. (Strangely, the low point occurred shortly

after

the turning point, but this technical glitch is generally overlooked.) After Valley Forge, the darkest hour was supposedly over. Come spring, once the soldiers had proved their worth, their troubles subsided. This mythic tale is based on the classic image of seasonal renewal, not historical documentation. Although hardships continued and even worsened until the end of the war, and although mutinies became rampant, the Valley Forge story serves to suppress these later difficulties. Narratives can refer to “suffering soldiers” at

a precise, well-defined time, without including the more serious uprisings that followed. By telling the story of the soldiers' plight there, writers do not have to visit it later on, when a spirit of resistance swept through the Continental Army.

Finally, Valley Forge makes for a powerful story because many soldiers died. In fact, the deaths were primarily due to camp diseasesâcold and hunger took few livesâbut that is rarely stated because disease evokes little sense of drama or patriotic sentiment. (More soldiers actually lost their lives because of disease than at the hands of the enemy during the Revolutionary War.

37

) Still, a death toll always helps a story along. The winter at Valley Forge was so severe, we are led to believe, that people actually perished because of itâand all without raising a fuss. Such patriots they must have been!