Founding Myths (33 page)

Authors: Ray Raphael

Sometimes, as in

The Patriot,

the good-versus-bad theme is deafening; often, it is muted but still audible. Popular writers today, in a

tone reminiscent of Mercy Otis Warren, give some notice to the brutal civil war, but they find ways of qualifying any condemnation of the patriots. In

Liberty!

Thomas Fleming refers to “the savage seesaw war,” but the only examples of savagery he presents were committed by the other side. Thomas Brown, he reports, hanged thirteen wounded patriots “in the stairwell of his house, where he could watch them die from his bed.”

26

The reporting of such callousness is calculated to leave a firmly biased impression on the reader. Fleming fails to note that the hangings did not take place in Brown's

own

house, as implied; that if Brown was in bed, it was because he had just been wounded; that the hangings had been ordered by his superiors; and that the man who originally spread the rumor, David Ramsay, later disavowed it. Instead, he restates without question the conventional story about this Tory villain, treating him as the “devil incarnate,” in the words of one nineteenth-century historian.

27

Robert Leckie, in

George Washington's War

, offers a vivid description of patriots mowing down loyalists who were trying to surrender at King's Mountain:

The rebel blood was up, their vengeance fed by the memory of the Waxhaws. “Buford! Buford!” they shouted. “Tarleton's Quarter! Tarleton's Quarter!” They pursued their frightened victims as they ran to a hollow place on the hilltop and cowered there in horror. One by one, the frontiersmen cut them down, sometimes singling out neighbors by name before they fired. Many of the Patriots thirsted to revenge themselves on the deaths of relatives and friends who were murdered by the Tories. Their eyes glittered maniacally as they loaded and fired . . . loaded and fired . . . At last Major Evan Shelby called on the Loyalists to throw down their arms. They did, but the rebel rifles still blazed. [Ellipses as in the original.]

28

But were these

real

patriots who acted so savagely? Not exactly. They were illiterate “Irish and Scots-Irish” who called their rifles “Sweet

Lips” or “Hot Lead.” “None of them could have quoted a line from Tom Paine's

Common Sense

,” Leckie writes, “and the phrase

Declaration of Independence

meant about as much to them as it did to their livestock.”

29

They were animals, not Americans; their deeds need not reflect poorly on the cause. Undue cruelties attributed to Americans must somehow be deflected, if they cannot be defended.

Many of today's textbooks continue to slant their coverage of the brutal civil war in the South. “Loyalist bands roamed the backcountry,” reports a middle-school text. “They plundered and burned Patriot farms, killing men, women, and children.” Treatment of the other side, by contrast, is far more respectful: “Francis Marion led his men silently through the swamps. They attacked without warning, then escaped. Marion's guerrilla attacks were so efficient that he won the nickname âSwamp Fox.' ” One side plunders, burns, and kills, but when the other side does likewise, it is merely being “efficient.” The language tells us very clearly how we should react.

30

Another middle-school text announces that “the southern war was particularly brutal” and “pitted AmericansâPatriots versus Loyalistsâagainst each other in direct combat.” This much is true, but it says no more about American brutality; instead, it states clearly that the British “destroyed crops, farm animals, and other property as they marched through the South” and mentions only one man by name: Banastre Tarleton, the British officer who “sowed fear throughout the South by refusing to take prisoners and killing soldiers who tried to surrender.”

31

A college text tips its hand with an adverb: “The colony of Georgia was

ruthlessly

overrun [by the British] in 1778â1779.” (Emphasis added.) Significantly, this text describes no American advanceânot even the purposive “scorched earth” annihilation of Iroquois lands, villages, and people in the North (see

chapter 14

)âas “ruthless.”

32

Such biased language is not new; in fact, this exact same sentence appears in the first edition of the textbook, published in 1956.

33

But due to “textbook lag” (see Afterword), the words persist and still have force, despite cultural changes in sensitivities since the midâtwentieth century.

Some textbooks now display more balance, attributing blame to both sides. In South Carolina, says one college text, “Most of the upcountry was stripped bare. As each side took control, neighbors attacked each other, plundered each other's farms, and carried away each other's slaves.”

34

Another college text offers the usual fareâ“Banastre Tarleton led one especially vicious company of loyalists who slaughtered civilians and murdered many who surrendered”âbut follows this with a parallel account of an American leader: “In retaliation, planter and merchant Thomas Sumter organized 800 men who showed a similar disregard to regular army procedures, raiding largely defenseless loyalist settlements near Hanging Rock, South Carolina, in August 1780.”

35

Such passages convert what used to appear as liabilitiesâthe uncivilized acts committed by some Americans, which undercut the national image of moral superiorityâinto teachable moments. Unbiased reporting of the brutal civil war in the Southern interior exposes the cycle of revenge and its unseemly consequences. Insofar as this message is received and internalized, senseless wars become less likely. On the other hand, pointing to atrocities committed only by the enemy panders to instincts of revenge, always the fodder of war hawks. Retributive violence becomes viewed as rational, leading otherwise decent people to sanction brutal acts they would normally condemn.

Â

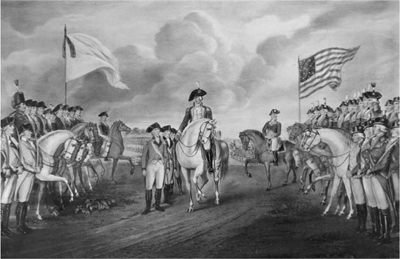

“Everyone realized that this surrender meant the end.”

The Surrender of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown, 19 October 1781.

Lithograph by Nathaniel Currier, 1852, based on painting by John Trumbull, 1787âcirca 1828.

O

n October 19, 1781, Lord Cornwallis formally surrendered his entire armyâsome 8,000 troopsâto George Washington at Yorktown, Virginia.

1

When Lord North, the British prime minister, heard the news, he exclaimed, “Oh, God, it is all over!” So ended the Revolutionary War.

This story is repeated in virtually every narrative account of the American Revolution. The notion of a decisive final battle constitutes a neat and tidy conclusion to the war, placing America firmly in control of her own destiny. “The great British army was surrendering,” writes Joy Hakim in her popular textbook. “David had licked Goliath. . . . A superpower had been defeated by an upstart colony.”

2

“CARRYING ON THE WAR”

Not everybody at the time saw it that way. In the wake of Yorktown, George Washington insisted that the war was not yet over, and King George III was not ready to capitulate. In fact, the fighting continued for over a yearâbut this part of history is rarely told. To stick to the story we like, we declare that people who engaged in subsequent battles were somehow mistakenâtheir fighting was some sort

of illusion. “Washington considered the country still at war,” writes A. J. Langguth in his bestselling book

Patriots

, “and George III was under that same

misapprehension.

”

3

When King George III heard of Cornwallis's surrender at Yorktown, he did not respond as fatalistically as did Lord North. “I have no doubt when men are a little recovered of the shock felt by the bad news,” he said, “they will find the necessity of carrying on the war, though the mode of it may require alterations.”

4

Washington was worried that the British Crown might respond this wayâso worried, in fact, that he redoubled his efforts to build up the Continental Army. On October 27, only ten days after the victory at Yorktown, the commander in chief urged Congress to continue its “preparation for military Operations”; a failure to pursue the war, he warned, would “expose us to the most disgracefull Disasters.”

5

In the following weeks, Washington repeated this warning more than a dozen times.

6

“Yorktown was an interesting event,” he wrote, but it would only “prolong the casualties” if Americans relaxed their “prosecution of the war.” Candidly, he confessed:

My greatest Fear is that Congress, viewing this stroke in too important a point of Light, may think our Work too nearly closed, and will fall into a State of Languor and Relaxation; to prevent this Error, I shall employ every Means in my Power.

7

Heeding Washington's advice, Congress called on the states to supply the same number of soldiers they had furnished the preceding year. But the states were financially strapped, and their citizens were tiring of war. They failed to meet their quotas, and Washington did not receive enough men to undertake the offensive operations he had contemplated.

8

Meanwhile, the British and French continued to battle for control of the seas. In the West Indies, six months after Yorktown, British seamen defeated the French fleet that had cut off the lines of supply

during the siege of Yorktown. With the French naval presence weakened, the British would be able to regroup and take the offensive; they could move their vast armies by sea to support any land operation they chose.

Washington was not the only American general worrying about this. Nathanael Greene, who had hoped to lead an attack on Charleston, suddenly expressed concern that the British might attack him instead.

9

On June 5, 1782, more than seven months after Yorktown, Washington wrote to the United States secretary of foreign affairs about the need to undertake “vigorous preparations for meeting the enemy.”

10

Finally, on August 4, the commanders of the British army and navy in North America informed Washington that the Crown was prepared to recognize “the independency of the thirteen Provinces,” providing only that loyalists receive full compensation for seized property and that no further property be confiscated. It seemed the war was coming to an end at lastâbut Washington was not buying it.

11

Not until a peace treaty was signed and British troops had returned home would he relax his guard. In his general orders for August 19, 1782âten months after Yorktownâhe wrote: “The readiest way to procure a lasting and honorable peace is to be fully prepared vigorously to prosecute War.”

12

The British then offered to suspend all hostilities, but Washington still wouldn't bite. Right at this moment, he received word that Lord Rockingham, the British prime minister believed to be responsible for the peace overtures, had died. The American commander in chief, who placed little stock in the fickle nature of British politics, assumed Rockingham would be replaced by a hard-liner. On September 12 he wrote: “Our prospect of Peace is vanishing. The death of the Marquis of Rockingham has given shock to the New Administration, and disordered its whole System. . . . That the King will push the War as long as the Nation will find Men or Money, admits not of a doubt in my mind.”

13

A full year after Yorktown, Washington warned Nathanael Greene:

In the present fluctuating state of British Councils and measures, it is extremely difficult to form a decisive opinion of what their real and ultimate objects are. . . . [N]otwithstanding all the pacific declaration of the British, it has constantly been my prevailing sentiment, the principal Design was, to gain time by lulling us into security and wasting the Campaign without making any effort on the land.

14

A preliminary peace treaty was signed on November 30, 1782âbut even that was not enough to satisfy the ever-suspicious American commander. On March 19, 1783, one year and five months after Yorktown, Washington was still keeping his guard up: “The Articles of Treaty between America and Great Britain . . . are so very inconclusive . . . that we should hold ourselves in a hostile position, prepared for either alternative, War or Peace. . . . I must confess, I have my fears, that we shall be obliged to worry thro' another Campaign, before we arrive at that happy period, which is to crown all our Toils.”

15