Founding Myths (18 page)

Authors: Ray Raphael

Â

“Jefferson's Declaration of Independence was great from the moment he wrote it.”

Thomas Jefferson Writing the Declaration of Independence.

Painting by Howard Pyle, 1898.

S

ince the Declaration of Independence was undeniably a great document, we naturally assume that only a great mind could have created it. That mind supposedly belonged to Thomas Jefferson, the genius of the Revolution. Jefferson's image has suffered of late because DNA evidence suggests he fathered children with his slave, Sally Hemingsâbut few question the quality or cogency of his thinking, or the belief that only a man of Jefferson's intellectual caliber could have drafted the momentous document that set us apart as an independent nation.

In

Liberty!

Thomas Fleming notes that Jefferson did not boast about his authorship of the Declaration of Independence. The document contained no “new principles or new arguments,” Jefferson admitted. Instead, it was “intended to be an expression of the American mind.” Too much “modesty,” Fleming complains. There was no “American mind” at the time. The Declaration, despite Jefferson's disclaimers, was all his own doing: “Jefferson poured into it his experience as an opponent of aristocratic privilege in Virginia,” Fleming argues. Only Jefferson could have said the things he did. The visuals accompanying the text underline his thesis: we see a portrait of Jefferson brooding

over a candlelit draft, followed by a facsimile of the draft itself, with many of Jefferson's deletions and additions.

1

Joseph Ellis presents a more complex version of the same argument. In

American Sphinx

, winner of the National Book Award for nonfiction in 1997, Ellis notes that Jefferson was in a position to draw on the works of many others, including George Mason, who had just drafted a very similar document, the Virginia Declaration of Rights. Ellis then lists other possible influences on Jefferson: the social contract theory of John Locke, the moral philosophy of the Scottish Enlightenment, and contemporary books on rhetoric and the art of the spoken word. At this juncture, Ellis offers an apt observation:

The central problem with all these explanations, however, is that they make Jefferson's thinking an exclusive function of books. . . . There is a long-standing scholarly traditionâone might call it the scholarly version of poetic licenseâthat depends on the unspoken assumption that what one thinks is largely or entirely a product of what one reads.

This point is well taken. Certainly we are more than the sum of what we read. But if not from books, where did Jefferson's ideas come from? “From deep inside himself,” Ellis posits. The Declaration of Independence represented “the vision of a young man projecting his personal cravings” for a better world.

2

Ellis's view of the creative process sets individual imagination above all else. The internal vision of the creatorâa “wise man”âis not tarnished by external influences. This romantic notion ignores the political setting in which Jefferson lived. There was a revolution going on, and it had been brewing for more than a decade. People talked and wrote to each other incessantly. They engaged in hearty and contentious debate. They designed and circulated petitions and declarations. In those critical years patriots throughout the British colonies worked themselves up to the fever pitch that revolution requires. Revolutionary phrases were stated and repeated so often that

they entered the very language. They became the common currency of what might very rightly be called “the American mind.”

Most plain folk in America had not studied John Locke's

Second Treatise on Government

, but in any country tavern, ordinary farmers could recite the principle of the “social contract”: government is rooted in the people, and rulers who forget this are ripe for a fall.

3

From firsthand experience and incessant repetition, they knew all they needed to know about popular sovereignty. For the antecedents and precedents that influenced the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson had only to look to the nearest tavern or meetinghouse, wherever patriots gathered. The most significant “source” for his forceful statement of popular sovereignty was, appropriately, the people themselvesâthe “American mind” that he himself rightfully credited.

THE “OTHER” DECLARATIONS OF INDEPENDENCE

On October 4, 1774, twenty-one months before the Continental Congress approved its public explanation of why it had broken from Britain, the people of Worcester, Massachusetts, declared that they were ready for independence. (See

chapter 4

.) Worcester was certainly in the vanguard, but patriots in other towns and other colonies also declared their willingness to break from Britain several months before a committee of the Second Continental Congress asked Thomas Jefferson to draft a formal declaration. In Jefferson's Virginia, the issue of independence preempted all others during the spring of 1776. Common folk, not just the famous patricians-turned-statesmen, came to embrace independence for political, economic, and ideological reasons.

4

Beyond noble principles, fear of slaves and Indians contributed to the desire for independence. (See

chapter 9

.) In the April elections voters turned out in great numbersâand they stunned the more cautious politicians. Representatives who opposed independence or a republican form of government were turned out.

5

Before sending off their new delegates to the Virginia Convention,

constituents of several counties gave them specific, written instructions to vote for a declaration of independence. Charles Lee wrote to Patrick Henry: the “spirit of the people . . . cr[ies] out for this Declaration.”

6

Jefferson himself was in Virginia during that time. “I took great pains to enquire into the sentiments of the people,” he wrote on May 16, 1776, just a few weeks before he would pen his famous draft. “I think I may safely say nine out of ten are for it [independence].”

7

The people had spoken, the stage was set. On May 15, 1776, the Virginia Convention instructed its delegates to the Continental Congress to initiate a declaration of independence.

Acting more swiftly than the Continental Congress, Virginia proceeded to declare independence on its own. George Mason then prepared a draft for Virginia's “Declaration of Rights,” which circulated widely in June 1776. It appeared in the

Pennsylvania Gazette

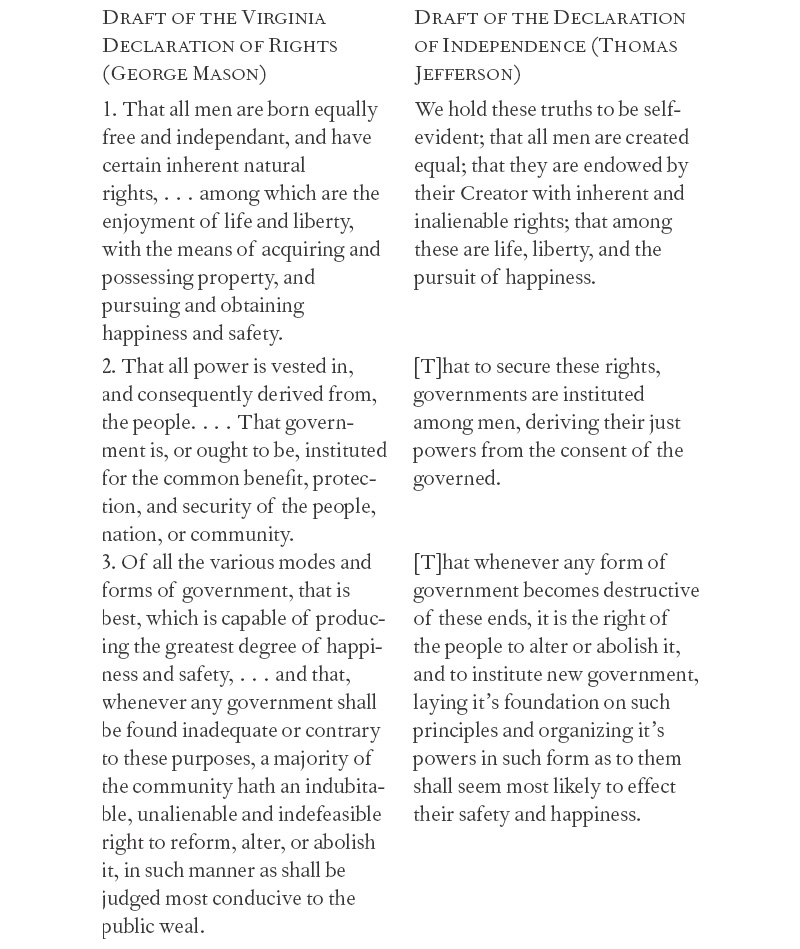

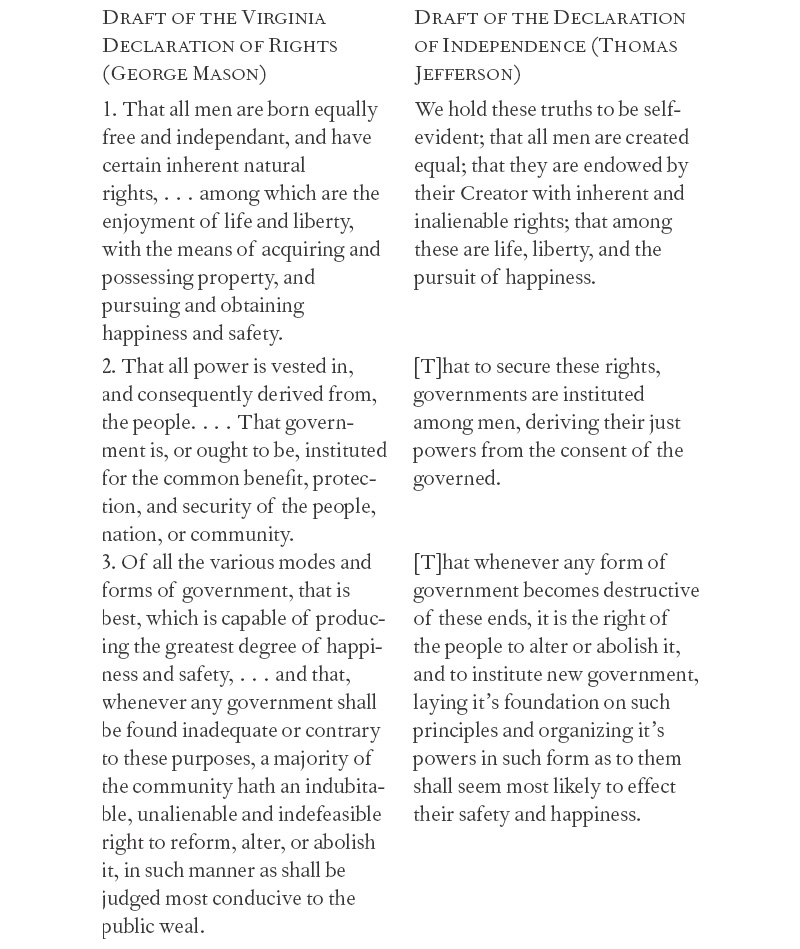

on June 12, the day after Jefferson was appointed to the five-man committee that would draft a national declaration. In Philadelphia, Jefferson and the other members of the committee no doubt examined these words closely. Two weeks later, Jefferson presented his own refinement of Mason's draft:

8

Although Jefferson's prose flows more smoothly from point to point than Mason's, he certainly introduced no new concepts. Many key phrases were merely rearranged. Jefferson in no sense “copied” the Virginia Declaration, but he was evidently influenced by it. That should come as no surprise. This was a time of frenzied but collective agitation, and the Revolution's participants continually referred to each other's words and propositions. In all likelihood Mason himself was familiar with Jefferson's

Summary View of the Rights of British

America

, written two years earlier. Undoubtedly, both men had read classic English and Scottish works that espoused revolutionary principles, and both were privy to expressions that were common parlance among their peers. Mason and Jefferson were tapping into the same rich source.

Virginia's Declaration was only one of many. Historian Pauline Maier has discovered ninety “declarations” issued by state and local communities in the months immediately preceding the congressional declaration.

9

(She does not include the Worcester instructions, written back in 1774.) Taken together, these reveal a groundswell of political thinking in support of independence. Jefferson and Mason drafted their declarations with full knowledge that others were doing the same, even if they did not consult every state and local document.

Most of these declarations took the form of instructions by towns, counties, or local associations to their representatives in state conventions, telling them to instruct

their

representatives in Congress to vote for independence. The chain of command was clear: representatives at every level were to do the bidding of their constituents. The custom of issuing instructions to representatives did not originate with the American Revolution, but never before had local instructions expressed views of such monumental importance. Now more than ever, patriots insisted that the business of government remain under their immediate control. Witness the “Committee for the Lower District of Frederick County [Maryland]”:

Resolved, unanimously

, That as a knowledge of the conduct of the Representative is the constituent's only principle and permanent security, we claim the right of being fully informed therein, unless in the secret operations of war; and that we shall ever hold the Representative amenable to that body from whom he derives his authority.

10

Many of the instructions, while granting new powers to Congress, asserted that the states must retain “the sole and exclusive right” to

govern their own internal affairs.

11

People were not about to relinquish any of their political “independence,” even to other Americans.

Several of the local declarations offer succinct expressions of the social contract theory. Again from Frederick County:

Resolved, unanimously

, That all just and legal Government was instituted for the ease and convenience of the People, and that the People have the indubitable right to reform or abolish a Government which may appear to them insufficient for the exigency of their affairs.

12

Patriots from Buckingham County, Virginia, issued a similar declaration, then followed with an optimistic vision that would have made the visionary Mr. Jefferson proud: they prayed that “a Government may be established in

America

, the most free, happy, and permanent, that human wisdom can contrive, and the perfection of man maintain.”

13

Like the later Declaration, many of these earlier documents listed specific grievancesâoften more concisely and pointedly than Jefferson would do.

14

Delegates at more than twenty conventions or town meetings signed off by pledging to support independence with their “lives and fortunes,” foretelling the famous conclusion to the congressional declaration: “We mutually pledge our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor.” Some of these added creative touches to this standard oath: Boston delegates pledged “their lives and the remnants of their fortunes,” while patriots from Malden, Massachusetts, concluded: “Your constituents will support and defend the measure to the last drop of their blood, and the last farthing of their treasure.”

15