Eyes on the Street: The Life of Jane Jacobs (24 page)

Read Eyes on the Street: The Life of Jane Jacobs Online

Authors: Robert Kanigel

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Women, #History, #United States, #20th Century, #Political Science, #Public Policy, #City Planning & Urban Development

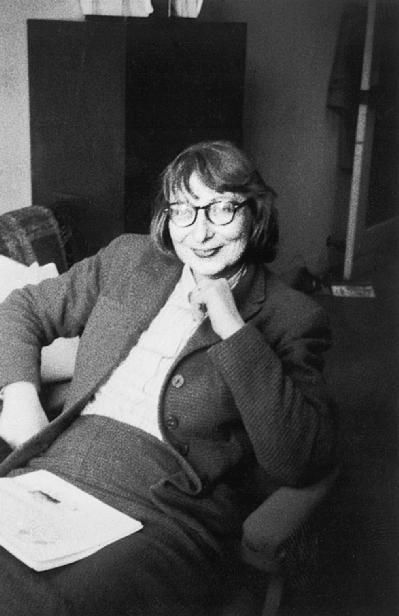

Jane, career woman, at

Architectural Forum,

ca. 1960

Credit 12

For months now, in the wake of her visits to Philadelphia and East Harlem, Jane had been troubled by the great gulf between how things were supposed to work in the new modernist city and how they really did. She needed to say something about it; that intellectual tickle, that writerly need to

express

, had grown. She had two, maybe three weeks to prepare her talk. As if composing any ordinary article, she wrote it out first. Not that she would simply read it out loud; that would be deadly.

On the other hand, notes or flash cards might leave too much room for a podium meltdown once she stepped up to speak. So she memorized her talk, all fifteen hundred words. Bob made her try it out on him first.

First my knees trembled and my voice trembled because I had to get through it. But he made me say it over and over to him so I could do it without that happening…So when the time came and I had to give the speech, I went into some kind of…I mesmerized myself. I have no memory of doing it. I just said it. I blanked out and said it without all this trembling and everything, and got away with it.

She began with East Harlem, and how, in the rehousing of fifty thousand people in the projects, more than a thousand stores had disappeared from the neighborhood. This was not just consumer goods and services made harder to come by; this was

community.

“A store,” she said memorably, “is also a storekeeper. One supermarket can replace thirty neighborhood delicatessens, fruit stands, groceries and butchers…But it cannot replace thirty storekeepers or even one.”

Candy stores, diners, and bars served as social centers. When sometimes they failed, social clubs, political clubs, and churches took over their empty storefronts. And if these, too, were gone? It was easy to joke about the poor ward heeler who’d lost his organization. But, Jane cautioned, “this is not really hilarious.” She continued,

If you are a nobody, and you don’t know anybody who isn’t a nobody, the only way you can make yourself heard in a large city is through certain well-defined channels. These channels all begin in holes in the wall. They start in Mike’s barbershop or the hole-in-the-wall office of a man called Judge, and they go on to the Thomas Jefferson Democratic Club where Councilman Favini holds court, and now you are started on up.

How all this worked couldn’t be formalized. But by the whole weight of her argument, it

needed

the shabby, low-rent, leftover spaces of poor city neighborhoods. It didn’t work so much in new buildings, in the secure, serenely ordered places of the world.

Places like

Stuyvesant Town.

Jane had reason to know about Stuyvesant Town; her sister lived there.

All through the late 1940s, 1950s, and beyond, the two of them, their husbands, and their children were in and out of each other’s homes, a half hour’s walk or a ride on the crosstown bus away, their families off together to museums, free concerts, the zoo. Betty and Jules Manson and their three children (aged three through eight in 1955) lived in one of a great eruption of new thirteen-story apartment buildings named after Peter Stuyvesant, the last mayor of New Amsterdam before it became New York City. The complex was built after the war to help remedy the housing shortage faced by returning GIs. Stuyvesant Town wasn’t a “project,” in that it wasn’t the work of federal housing agencies. It wasn’t built to serve the poor. But “project” it was in every other sense—vast, covering sixty-two acres, its three dozen redbrick towers all but identical, home to twenty thousand people.

In 1942,

from their perch six hundred feet above Madison Avenue in the headquarters of the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, as Samuel Zipp tells the story in his masterful

Manhattan Projects

, the company’s money men looked south and saw the whole East Side below the East Twenties as, weirdly, “vacant.” That is, they saw crumbling tenements ripe for investment, demolition, and reconstruction. Eventually, work crews rendered the whole eighteen-block Gashouse District, as the neighborhood was known, indistinguishable from European cities laid waste by war. But before they did, Met Life went through it, block by block, photographing streetscapes that would soon be gone.

One corner of the site did look pretty bad. But some of the rest of the neighborhood, if not exactly bustling with life, could pass for prosperous, with four- and five-story tenements lining well-kept streets. There were theaters, two schools, numerous ornate churches. Lewis Mumford himself would write of the gasworks that gave the neighborhood its name, that the sight of its “

tracery of iron, against an occasional clear lemon-green sky at sunrise” offered a memorably aesthetic moment. Journalists documenting the area’s death throes found, in Zipp’s words, “

a living neighborhood…[whose] residents viewed the place with simple affection, despite poverty and a declining population…[It] was the setting for the great events of ordinary life and had become as precious to them as the people with whom they had shared their lives.”

The Gashouse District was leveled. Stuyvesant Town rose in its place. By many measures it had to count as a success. Aimed squarely at the middle class, it boasted pretty landscaping, curving paths, relatively spacious

rooms, and a careful tenant selection process—which for years excluded blacks and other minorities. In these ways, if not in every other, it mirrored the new suburbs going up around the same time. Betty Manson’s daughter, Jane’s niece Carol, would recall fondly how, from her

bedroom window in apartment 10F of one of the buildings, she could look north to see the Empire State and Chrysler buildings. The window of her brother’s room looked south, across Fourteenth Street, to the older tenement neighborhood where they could watch people flying pigeons from the rooftops. Stuyvesant Town, she’d think, was as different as could be from Aunt Jane’s ramshackle Greenwich Village.

In her Harvard talk in 1956, Jane emphasized the similarities, more than the differences, between Stuyvesant Town, a middle-income development east of First Avenue in Lower Manhattan, and George Washington Houses, a low-income public housing project in New York’s East Harlem.

Credit 13

/

Credit 14

And, of course, it was as different as could be from East Harlem.

Only Jane thought it wasn’t so different from East Harlem after all, which is what she wanted to tell her Harvard audience.

To her, Stuyvesant Town seemed a creature of the same postwar planning impulse. Like East Harlem, it had no stores, virtually nothing but apartments. Like East Harlem, it was huge, occupying a great swath of real estate along the eastern edge of Manhattan, from First Avenue almost to the East River. As with the East Harlem projects the street grid had been torn up, new buildings plopped down into a great superblock. Butting up against Stuyvesant Town, Fifteenth and Sixteenth Streets now simply vanished at First Avenue. In numerous visits to her sister’s place, Jane had walked Stuyvesant Town’s lawn-lined paths and apartment hallways, and didn’t like what she saw.

“We all knew of Jane’s dislike for Stuyvesant Town,” says Carol, who recalls a breath of tension between the sisters about it. “I did not for a long time understand her antipathy to the place, since it was certainly cleaner, and less smelly, and with fewer rats and insects, than the buildings south of us. And the toilets and bathtubs I thought had nice lines, and the windows were larger, and I liked the parquet floors.” Over the years Stuyvesant Town’s hesitant early tufts of foliage and shafts of green would grow into a lush springtime canopy. To many among her listeners at Harvard, Stuyvesant Town had no business being mentioned in the same breath as East Harlem. It was middle income, not poor. It was private, not public. Maybe it wasn’t up to the standards of the Upper East Side or Gramercy Park, but compared to the East Harlem projects, rooms were bigger, the level of finish and care higher. Certainly it was easy to list all the ways in which it and East Harlem differed.

But Jane was drawing out what she saw as their similarities, which she saw as more telling. And she did so, oddly enough, through a kind of “figure-ground” reversal, by looking

outside

Stuyvesant Town to the streets around it: Take the elevator down from your tower apartment, step out along a broad curving walkway to Fourteenth Street, cross it, and

you were in another country. Now it was four- and five-story walk-ups, fire escapes parading down their streetside faces, basement grates poking up onto the sidewalks, streets crowded with people, small stores of every description. A feast for the senses (if for some an assault on them). Jane pictured “an unplanned, chaotic,

prosperous belt of stores, the camp followers around the Stuyvesant [Town] barracks.” And beyond, a yet more chaotic belt, of “the hand-to-mouth cooperative nursery schools, the ballet classes, the do-it-yourself workshops, the little exotic stores.” All this, “among the great charms of a city,” lay

outside

Stuyvesant Town.

“Do you see what this means?” Jane asked her audience. Some of the most essential and characteristic elements of city life had been extirpated from Stuyvesant Town and from East Harlem alike, “because there is literally no place for them in the new scheme of things.”

It was this “new scheme of things” that was Jane’s real subject. The architectural and planning notions of the postwar period wiped real neighborhoods clean away and supplanted them with places made uniform, inflexible, inhuman, and dull.

This

was the new scheme of things. It was “a ludicrous situation,” said Jane, “and it ought to give planners the shivers.”

At one point, as she told the story, Union Settlement had sought a spot in an East Harlem project where they could meet easily with adult residents. Well, there was no such place, anywhere—no place to meet and gather except maybe the laundry room in the basement. Did the project’s architects realize that relegating the social and public realm to the bowels of the basement made for a “social poverty beyond anything the slums ever knew”?

Jane wasn’t finished. She observed that some of the East Harlem projects were by now a decade old. Yet with enough time now elapsed to forge new social networks, residents still visited their old neighborhoods while few from outside came to visit them. Why? Because there was nothing for them there,

nothing to do.

Planners needed to learn from the stoops and sidewalks of the city’s livelier old parts. The open space of most urban redevelopment was a “giant bore,” whereas it “should be at least as vital as the slum sidewalk.”

“We are greatly misled,” she concluded, “by talk about bringing the suburb into the city.” The city had its own, very different virtues, “and we will do it no service by trying to beat it into some inadequate imitation of the noncity.”

—

When she emerged from the near-hypnotic state, or whatever it was that had gotten her through it, Jane learned her talk had been “

a big hit, because nobody had heard anybody saying these things before, apparently.” Lewis Mumford came up to her afterward, shook her hand, and “enthusiastically welcomed me,” as if to throw an arm around her and admit her to the club. “Into

the foggy atmosphere of professional jargon” of the conference, he’d write later, Jane “blew like a fresh, offshore breeze to present a picture, dramatic but not distorted,” of the human cost of the projects. Her appearance had