Eyes on the Street: The Life of Jane Jacobs (22 page)

Read Eyes on the Street: The Life of Jane Jacobs Online

Authors: Robert Kanigel

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Women, #History, #United States, #20th Century, #Political Science, #Public Policy, #City Planning & Urban Development

In 1956,

Forum

colleague William McQuade devoted the magazine’s informal

“Parentheses” column to a lady “who shall be nameless” but a photograph of whom, atop her steed, shows Jane. At workday’s end, McQuade wrote, she’d round up her bike from “among the ranks of Cadillacs” in a nearby garage. Then she’d pedal “down Fifth Avenue, south through the crowded department store district…[and] the impossible press of the garment district, on through the fallen petals and broken blossoms of the wholesale flower zone, and then down through wicked Greenwich Village until she reaches home, her house on Hudson Street.” McQuade’s journalistic bibelot offered a sample of the jibes Jane absorbed on her commute. “Get a horse,” she’d hear a lot. Or, “Watch out, girlie,

you’ll get hurt.” More recently, back on the bike again after the birth of her daughter, Mary, in January 1955, New Yorkers seemed warmer to her. “That’s a good idea,” she’d sometimes hear. Or “Good for you,” or “Take me with you.” Of course, her street critics never tired of pointing out:

“Your back wheel’s spinning.”

Jane’s marriage had all but begun on the bike, with a cycling honeymoon. After the war, she and Bob enjoyed what she’d call “

hitch-hiking with the fish”: they’d load their bikes on the train, get off somewhere within cycling distance of a fishing port, and, with their beat-up bags, hitch rides on fishing boats plying East Coast waterways. No reference to what Jane called this “intricate network of unofficial transport” appeared in any atlas or tourist map. They made no hotel reservations, yet always found someone to take them in. In a little town on Pamlico Sound in North Carolina, it was the owner of a local shrimp-packing plant. In Maine, it was the island butter maker and her lobsterman husband. One time, Jane would write, they feasted on lobster “direct from the sea into the galley cauldron, eaten on deck in a green and lavender twilight among the rock and evergreen islands of Penobscot Bay.”

Back on Hudson Street, they got their boys onto bikes early on. When he was three and Jimmy was five, Ned recalls, their parents renewed the Sunday bike excursions around town they’d enjoyed before the children were born. The kids were taught to

sit on the rear rack “with our feet in canvas saddlebags, our hands on the cyclist’s waist.” They never had an accident. They always had fun.

During this period, Jane made about

$10,000 a year—about twice what a

Forum

secretary made and probably more than Bob, who, after a stretch as assistant architect with a New York City agency, was just finding his way into hospital design. With two incomes, the Jacobses were doing well enough, but with two, then three, children at home and the old house a money drain, they were far from well off. Around this time they bought an encyclopedia on the installment plan; Jane would remember the payments dragging on forever.

But during the 1950s and early 1960s, time was probably scarcer than money for them. Soon after son Jimmy’s birth in 1948, Jane had hired a woman to take care of him while she was at work. Her name was

Glennie Lenear, an African American woman who came in on the subway every day from Queens and who’d work for the family for a dozen years. Jane did what she needed to around the house, but never warmed to everyday

domestic chores. From when he was five or six Jimmy remembers Aunt Betty, who lived across town in a new middle-income project called Stuyvesant Town, urging his mother to get a steam iron, to spiff up her clothes for work; it would be so much more efficient that way. But Jane saw nothing efficient about it; better just to take her clothes next door to the cleaners. She rarely shopped for groceries; more often, she made a list of what she needed and phoned it in to the local grocer, delivery coming a few hours later, a bill once a month.

Jane would become known for her first book’s warm account of her neighborhood’s shopkeepers—how she’d exchange a friendly nod each morning with Mr. Lofaro, the fruit dealer, how she’d leave a spare key with Joe Cornacchia, proprietor of the local deli. As a

New York Times

writer observed after the book came out, “Thornton Wilder’s loving portrait of the leisurely life of Grover’s Corners,” in

Our Town

, was “

no more romantic than Mrs. Jacobs’s affectionate portrait of a day and night in Hudson Street.” By 1955, she had lived there for seven years, in the Village for twenty—long enough, and stitched in enough, to feel protective of it. To outsiders, the wayward tracts of the Village, with tenement apartments atop hardware stores and trucks bebopping down crowded streets, might seem to offer little enough to protect. But by now the Village exerted a powerful hold on Jane. So when word got out that the city was bent on pushing a highway through Washington Square Park, she was among those who helped try to stop it.

Now, it so happens that this Washington Square Park—Waverly Place to West Fourth Street and MacDougal to University Place, ten acres shaded by pin oaks and yellow locust trees, benches lining its paths, the white marble Washington Arch looming over it—comes down to us as a cultural monument of the 1950s and 1960s; that its history went way back to the more genteel era of Henry James’s

Washington Square;

that, even before Bob Dylan and Allen Ginsberg frequented it, it was already a tourist destination, suburbanites from Jersey and the Island descending on it to get their fix of folk singers, chess players, and

cool.

But, please, forget all that: it wasn’t folk singers, beat poets, or historic preservationists who battled back the threat to the park, it was mothers—mothers for whose children the park was their playground, open space in a crowded city. When Jane’s brother Jim and his family came up to the city from South Jersey, the cousins would soon be trooping over to Washington Square, a ten- or fifteen-minute walk away. It was lovely, always full of people, and safe.

But

, beginning in the early 1950s, it was threatened.

“I have heard with alarm and

almost with disbelief,” Jane wrote Mayor Robert F. Wagner Jr. and the Manhattan borough president, Hulan Jack, “the plans to run a sunken highway through the center of Washington Square.” She went on to tell how she and Bob had

transformed their home from a slum, were raising their three children in the city, doing their best to make the city a better place to live; this awful scheme would undo all that.

It was June 1, 1955. She had joined the fight late in the game; the campaign to save Washington Square Park had been going on for several years, and would for several more. Jane was only a foot soldier. But this wasn’t the last time she would step into an urban turf war, and next time she’d be a general.

—

Early in 1955, Jane met

William Kirk, who took her on another tour, of another city, and changed her life.

For the past six years, Kirk had worked in New York City’s East Harlem at Union Settlement, which since the 1890s had provided health and social services to the neighborhood; Burt Lancaster of East 106th Street, the future actor, was one of its beneficiaries. The word “settlement” itself went back to the nineteenth century, when educated men and women in Victorian England settled in slums to live and work among the poor.

Kirk, whose official title was “headworker” but who functioned as executive director, had come out of Newcastle, Pennsylvania, an industrial town about fifty miles north of Pittsburgh. When Jane met him he was a big, lumbering, dark-haired man about seven years older than she who might have been mistaken for a longshoreman or union official except that he spoke with an accent more patrician than New York. He had graduated from Amherst College in 1931, attended the Virginia Seminary, was ordained an Episcopal priest in 1935. But as rector of a St. Louis church, he’d found that the social welfare side of his work meant more to him than the purely spiritual, and in 1949 he moved to New York to direct Union Settlement.

Now, six years later, Kirk saw the neighborhood reeling under new, disruptive forces no one could have foreseen. When he’d first moved into Union Settlement’s offices on East 104th Street, both sides of the street looked about the same, each solidly lined with familiar walls of tenements, stores at street level, busy life sprouting up from among them.

But now, in the mid-1950s, the south side of the street was gone, the tenements torn down, replaced by ranges of high-rise towers cascading off to the south—slab-sided structures of twelve or fourteen stories, each set amid park-like swaths of green, winding paths, and parking lots. They had been built to do good. But Kirk had come to feel that these big housing projects were doing less good than harm. He had no data, nothing like the hard evidence later studies would supply, maybe no words yet even to describe it. But he knew that storekeepers were disappearing from the neighborhood; friendships seemed discouraged, schools and churches weakened, the social fabric frayed. His daughter, Judy Kirk Fitzsimmons, recalls him from her youth as a man on a mission, the big projects all he could talk about. He’d come home in the evening to their apartment on Riverside Drive, sit down for dinner, “and that was the conversation every night,” about what the projects were doing to East Harlem.

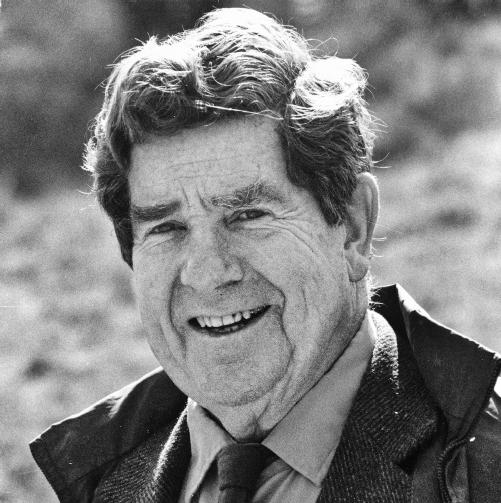

William Kirk, director of Union Settlement in East Harlem, New York City

Credit 11

East Harlem, be it noted, wasn’t Harlem, the great concentration of African American life and culture lying roughly between Columbia University on the west and the New York Central tracks along Park Avenue to the east. East Harlem lay on the other side of the tracks beside the East River, sprawling north from Ninety-sixth Street. In the mid-1950s, it was about a third each black, Puerto Rican, and white. The whites were mostly Italian; until the 1930s, East Harlem had been the largest Little Italy in America. In this one corner of Upper Manhattan lived 180,000 people, many more than in all of Jane’s own Scranton. Spanish was the language of many streets, shops, and homes, as spoken by migrants from Puerto Rico (an American dependency since the Spanish-American War). And it was poor, not here and there, as in the Village, but in

great swaths of tenements ranging over dozens of blocks. Many of these were old-law tenements built for the great waves of immigrants to New York in the late 1800s—cramped apartments, often four to a floor, back rooms giving onto dirty air shafts for their only light and air, several families sharing a

common toilet in the hall.

As recently as 1939, in what was then the most densely Italian part of East Harlem, four in five dwellings lacked central heating, two-thirds lacked tub or shower, more than half were without a private toilet.

What, exactly, was a slum?

Whatever it was, there were plenty of them in East Harlem. Crime was rampant. People were forever moving in and out.

No bank, according to one neighborhood observer, had loaned a dollar of mortgage money in East Harlem since before 1940.

Of course, everybody knew all this, and after World War II, efforts were begun to remedy the neighborhood’s housing evils; at a time when fifteen cents got you on the subway, $300 million in new housing had gone up since the 1940s, worth maybe $3 billion today. Beginning even earlier, in 1941, with East River Houses, and then with hurtling, unsettling rapidity after the war, blocks of tenements had been torn down, new eleven- and fourteen- and seventeen-story projects going up in their place. In time they would house

a fifth of East Harlem. It wasn’t just George Washington Houses, across 104th Street from Union Settlement. It was James Weldon Johnson Houses, ranging across six blocks between Third and Park Avenues, with more than 1,300 apartments. And Carver Houses, along Madison Avenue, with 1,246. And Lexington Houses, Taft Houses, Stephen Foster Houses…“Tear down the old,” New York mayor Fiorello La Guardia, a son of East Harlem, had urged in a 1944 speech. “Build up the new. Down with rotten, antiquated rat holes. Down with hovels. Down with disease. Down with crime…Let in the sun. Let in the sky.” And they had: clean, relatively spacious apartments, half a century newer than the tenements they’d displaced. They were “solid, institutional gigantic buildings,” one social worker would write, that promised “the long-awaited and highly touted attributes of sunshine, fresh air, and modern plumbing.”

And yet, from Bill Kirk’s perch on East 104th Street, something was wrong with this fine picture. His friend

Phil Will, he decided, needed to see what he saw in East Harlem. Will was a prominent Chicago architect who a few years later would become president of the American Institute of Architects. The specialty of his firm, Perkins & Will, was schools, but he’d earlier made a name for himself with Racine Courts, a model for low-rise public housing in Chicago. The two men had gotten to know each other through their wives, best friends in college, and across a span of twenty years had become close. So now, Kirk brought Will to East Harlem. “He wanted him to see how people worked, see the fabric of the community,”

recalls Kirk’s daughter, and to see what the new construction—this new

kind

of construction, really—was doing to it. Afterward, Will suggested they

approach Doug Haskell at

Architectural Forum

, whom he’d known since the 1940s.