Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things (52 page)

Read Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things Online

Authors: Charles Panati

Tags: #Reference, #General, #Curiosities & Wonders

First marketed in 1899 as a loose powder, Aspirin quickly became the

world’s most prescribed drug. In 1915, Bayer introduced Aspirin tablets. The German-based firm owned the brand name Aspirin at the start of World War I, but following Germany’s defeat, the trademark became part of the country’s war reparations demanded by the Allies. At the Treaty of Versailles in June 1919, Germany surrendered the brand name to France, England, the United States, and Russia.

For the next two years, drug companies battled over their own use of the name. Then, in a famous court decision of 1921, Judge Learned Hand ruled that since the drug was universally known as aspirin, no manufacturer owned the name or could collect royalties for its use. Aspirin with a capital

A

became plain aspirin. And today, after almost a century of aspirin use and experimentation, scientists still have not entirely discovered how the drug achieves its myriad effects as painkiller, fever reducer, and anti-inflammatory agent.

Under the Flag

Uncle Sam: 1810s, Massachusetts

There was a real-life Uncle Sam. This symbol of the United States government and of the national character, in striped pants and top hat, was a meat packer and politician from upstate New York who came to be known as Uncle Sam as the result of a coincidence and a joke.

The proof of Uncle Sam’s existence was unearthed only a quarter of a century ago, in the yellowing pages of a newspaper published May 12, 1830. Had the evidence not surfaced, doubt about a real-life prototype would still exist, and the character would today be considered a myth, as he was for decades.

Uncle Sam was Samuel Wilson. He was born in Arlington, Massachusetts, on September 13, 1766, a time when the town was known as Menotomy. At age eight, Sam Wilson served as drummer boy on the village green, on duty the April morning of 1775 when Paul Revere made his historic ride. Though the “shot heard round the world” was fired from nearby Lexington, young Sam, banging his drum at the sight of redcoats, alerted local patriots, who prevented the British from advancing on Menotomy.

As a boy, Sam played with another youthful patriot, John Chapman, who would later command his own chapter in American history as the real-life Johnny Appleseed. At age fourteen, Sam joined the army and fought in the American Revolution. With independence from Britain won, Sam moved in 1789 to Troy, New York, and opened a meat-packing company. Because

of his jovial manner and fair business practices, he was affectionately known to townsfolk as Uncle Sam.

It was another war, also fought against Britain on home soil, that caused Sam Wilson’s avuncular moniker to be heard around the world.

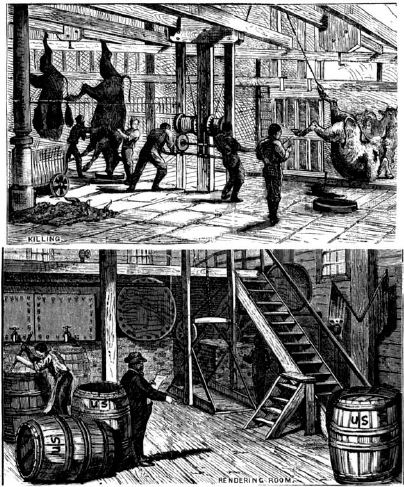

During the War of 1812, government troops were quartered near Troy. Sam Wilson’s fair-dealing reputation won him a military contract to provide beef and pork to soldiers. To indicate that certain crates of meat produced at his warehouse were destined for military use, Sam stamped them with a large “U.S.” —for “United States,” though the abbreviation was not yet in the vernacular.

On October 1, 1812, government inspectors made a routine tour of the plant. They asked a meat packer what the ubiquitously stamped “U.S.” stood for. The worker, himself uncertain, joked that the letters must represent the initials of his employer, Uncle Sam. The error was perpetuated. Soon soldiers began referring to all military rations as bounty from Uncle Sam. Before long, they were calling all government-issued supplies property of Uncle Sam. They even saw themselves as Uncle Sam’s men.

The first Uncle Sam illustrations appeared in New England newspapers in 1820. At that time, the avuncular figure was clean-shaven and wore a solid black top hat and black tailcoat. The more familiar and colorful image of Uncle Sam we know today arose piecemeal, almost one item at a time, each the contribution of an illustrator.

Solid red pants were introduced during Andrew Jackson’s presidency. The flowing beard first appeared during Abraham Lincoln’s term, inspired by the President’s own beard, which set a trend at that time. By the late nineteenth century, Uncle Sam was such a popular national figure that cartoonists decided he should appear more patriotically attired. They adorned his red pants with white stripes and his top hat with both stars and stripes. His costume became an embodiment of the country’s flag.

Uncle Sam at this point was flamboyantly dressed, but by today’s standards of height and weight he was on the short side and somewhat portly.

It was Thomas Nast, the famous German-born cartoonist of the Civil War and Reconstruction period, who made Uncle Sam tall, thin, and hollow-cheeked. Coincidentally, Nast’s Uncle Sam strongly resembles drawings of the real-life Sam Wilson. But Nast’s model was actually Abraham Lincoln.

The most famous portrayal of Uncle Sam—the one most frequently reproduced and widely recognized—was painted in this century by American artist James Montgomery Flagg. The stern-faced, stiff-armed, finger-pointing figure appeared on World War I posters captioned: “I Want You for U.S. Army.” The poster, with Uncle Sam dressed in his full flag apparel, sold four million copies during the war years, and more than half a million in World War II. Flagg’s Uncle Sam, though, is not an Abe Lincoln likeness, but a self-portrait of the artist as legend.

A nineteenth-century meat-packing plant in upstate New York; birthplace of the Uncle Sam legend

.

During these years of the poster’s peak popularity, the character of Uncle Sam was still only a myth. The identity of his prototype first came to light in early 1961. A historian, Thomas Gerson, discovered a May 12, 1830, issue of the New York

Gazette

newspaper in the archives of the New-York Historical Society. In it, a detailed firsthand account explained how Pheodorus Bailey, postmaster of New York City, had witnessed the Uncle Sam legend take root in Troy, New York. Bailey, a soldier in 1812, had accompanied government inspectors on the October day they visited Sam Wilson’s meat-packing plant. He was present, he said, when a worker surmised that the stamped initials “U.S.” stood for “Uncle Sam.”

Sam Wilson eventually became active in politics and died on July 31,

1854, at age eighty-eight. A tombstone erected in 1931 at Oakwood Cemetery in Troy reads: “In loving memory of ‘Uncle Sam,’ the name originating with Samuel Wilson.” That association was first officially recognized during the administration of President John F. Kennedy, by an act of the Eighty-seventh Congress, which states that “the Congress salutes ‘Uncle Sam’ Wilson of Troy, New York, as the progenitor of America’s National symbol of ‘Uncle Sam.’ “

Though it may be stretching coincidence thin, John Kennedy and Sam Wilson spoke phrases that are strikingly similar. On the eve of the War of 1812, Wilson delivered a speech, and a plan, on what Americans must do to ensure the country’s greatness: “It starts with every one of us giving a little more, instead of only taking and getting all the time.” That plea was more eloquently stated in John Kennedy’s inaugural address: “ask not what America will do for you—ask what you can do for your country.”

Johnny Appleseed: 1810s, Massachusetts

Sam Wilson’s boyhood playmate John Chapman was born on September 26, 1774, in Leominster, Massachusetts. Chapman displayed an early love for flowering plants and trees—particularly apple trees. His interest progressed from a hobby, to a passion, to a full-fledged obsession, one that would transform him into a true American folk character.

Though much lore surrounds Chapman, it is known that he was a devoted horticulturist, establishing apple orchards throughout the Midwest. He walked barefoot, inspecting fields his sapling trees had spawned. He also sold apple seeds and saplings to pioneers heading farther west, to areas he could not readily cover by foot.

A disciple of the eighteenth-century Swedish mystic Emanuel Swedenborg, John Chapman was as zealous in preaching Scripture as he was in planting apple orchards. The dual pursuits took him, barefooted, over 100,000 square miles of American terrain. The trek, as well as his demeanor, attire, and horticultural interests, made him as much a recognizable part of the American landscape as his orchards were. He is supposed to have worn on his head a tin mush pan, which served both as a protection from the elements and as a cooking pot at his impromptu campsites.

Frontier settlers came to humorously, and sometimes derisively, refer to the religious fanatic and apple planter as Johnny Appleseed. American Indians, though, revered Chapman as a medicine man. The herbs catnip, rattlesnake weed, horehound, and pennyroyal were dried by the itinerant horticulturist and administered as curatives to tribes he encountered, and attempted to convert.

Both Sam Wilson and John Chapman played a part in the War of 1812. While Wilson, as Uncle Sam, packaged rations for government troops, Chapman, as Johnny Appleseed, traversed wide areas of northern Ohio barefoot, alerting settlers to the British advance near Detroit. He also

warned them of the inevitable Indian raids and plundering that would follow in the wake of any British destruction. Later, the town of Mansfield, Ohio, erected a monument to John Chapman.

Chapman died in March of 1845, having contracted pneumonia from a barefoot midwinter journey to a damaged apple orchard that needed tending. He is buried in what is known today as Johnny Appleseed Park, near the War Memorial Coliseum in Fort Wayne, Indiana, the state in which he died.

Although Johnny Appleseed never achieved the fame of his boyhood playmate Uncle Sam, Chapman’s likeness has appeared on commemorative U.S. stamps. And in 1974, the New York and New England Apple Institute designated the year as the Johnny Appleseed Bicentennial. Chapman’s most enduring monuments, however, are the apple orchards he planted, which are still providing fruit throughout areas of the country.

American Flag: Post-1777, New England

So much patriotism and sacrifice are symbolized by the American flag that it is hard for us today to realize that the star-spangled banner did not have a single dramatic moment of birth. Rather, the flag’s origin, as that of the nation itself, evolved slowly from humble beginnings, and it was shaped by many hands—though probably not those of Betsy Ross. The latest historical sleuthing indicates that her involvement, despite history book accounts, may well have been fictive. And no authority today can claim with certainty who first proposed the now-familiar design, or even when and where the Stars and Stripes was first unfurled.

What, then, can we say about the origin of a flag that the military salutes, millions of schoolchildren pledge allegiance to, and many home owners hang from a front porch pole every Fourth of July?

It is well documented that General George Washington, on New Year’s Day of 1776, displayed over his camp outside Boston an improvised “Grand Union Flag.” It combined both British and American symbols. One upper corner bore the two familiar crosses—St. George’s for England, and St. Andrew’s for Scotland—which had long been part of the British emblem. But the background field had thirteen red and white stripes to represent the American colonies. Since the fighting colonists, including Washington, still claimed to be subjects of the British crown, it’s not surprising that their homemade flag should carry evidence of that loyalty.

The earliest historical mention of an entirely American “Stars and Stripes” flag—composed of thirteen alternating red and white stripes, and thirteen stars on a blue field—is in a resolution of the Continental Congress dated June 14, 1777. Since Congress, and the country, had more urgent matters to resolve than a finalized, artistic flag design, the government stipulated no specific rules about the flag’s size or arrangement of details. It even failed to supply Washington’s army with official flags until 1783, after all the major war battles had ended.

Francis Scott Key, composer of “The Star-Spangled Banner

.”

During the Revolutionary War, the American army and navy fought under a confused array of local, state, and homemade flags. They were adorned variously with pine and palmetto trees, rattlesnakes, eagles, stripes of red, blue, and yellow, and stars of gold—to mention a few.