Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things (49 page)

Read Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things Online

Authors: Charles Panati

Tags: #Reference, #General, #Curiosities & Wonders

Today a wide variety of non-sodium, non-aspirin antacids neutralize

stomach acid. A glance at the medicine chest shelf will reveal that the modern components are aluminum, calcium, bismuth, magnesium, and phosphates, and the one ancient ingredient is dried milk solids.

Cough Drops: 1000

B.C

., Egypt

A cough’s main purpose is to clear the air passage of inhaled foreign matter, chemical irritants, or, during a head cold, excessive bodily secretions. The coughing reflex is part voluntary, part involuntary, and drugs that reduce the frequency and intensity of coughs are called cough suppressors or, technically, antitussives.

Many of these modern suppressor chemicals—like the narcotic codeine—act in the brain to depress the activity of its cough center, reducing the urge to cough. Another group, of older suppressors, acts to soothe and relax the coughing muscles in the throat. This is basically the action of the oldest known cough drops, produced for Egyptian physicians by confectioners three thousand years ago.

It was in Egypt’s New Kingdom, during the Twentieth Dynasty, that confectioners produced the first hard candies. Lacking sugar—which would not arrive in the region for many centuries—Egyptian candymakers began with honey, altering its flavor with herbs, spices, and citrus fruits. Sucking on the candies was found to relieve coughing. The Egyptian ingredients were not all that different from those found in today’s sugary lozenges; nor was the principle by which they operated: moistening an irritated dry throat.

The throat-soothing candy underwent numerous minor variations in different cultures. Ingredients became the distinguishing factor. Elm bark, eucalyptus oil, peppermint oil, and horehound are but a few of the ancient additives. But not until the nineteenth century did physicians develop drugs that addressed the source of coughing: the brain. And these first compounds that depressed the brain’s cough reflex were opiates.

Morphine, an alkaloid of opium, which is the dried latex of unripe poppy blossoms, was identified in Germany in 1805. Toward the close of the century, in 1898, chemists first produced heroin (diacetylmorphine), a simple morphine derivative. Both agents became popular and, for a time, easily available cough suppressants. A 1903 advertisement touted “Glyco-Heroin” as medical science’s latest “Respiratory Sedative.”

But doctors’ increasing awareness of the dangers of dependency caused them to prescribe the drugs less and less. Today a weaker morphine derivative, codeine (methylmorphine), continues to be used in suppressing serious coughs. Since high doses of morphine compounds cause death by arresting respiration, it is not hard to understand how they suppress coughing.

Morphine compounds opened up an entirely new area of cough research. And pharmacologists have successfully altered opiate molecules to produce synthetic compounds that suppress a cough with less risk of inducing a drug euphoria or dependency.

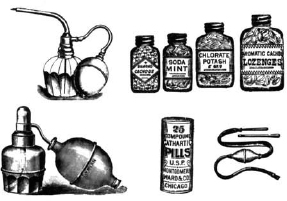

Turn of the century remedies: Throat atomizer (top), nasal model; various lozenges for coughs, hoarseness, halitosis, and constipation; syringe, for when tablets fail

.

But these sophisticated remedies are reserved for treating serious, life-threatening coughs and are available only by prescription. Millions of cold sufferers every winter rely on the ancient remedy of the cough drop. In America, two of the earliest commercial products, still popular today, appeared during the heyday of prescribing opiate suppressors.

Smith Brothers

. Aside from Abraham Lincoln, the two hirsute brothers who grace the box of Smith Brothers Cough Drops are reputed to be the most reproduced bearded faces in America. The men did in fact exist, and they were brothers. Andrew (on the right of the box, with the longer beard) was a good-natured, free-spending bachelor; William was a philanthropist and an ardent prohibitionist who forbade ginger ale in his home because of its suggestive alcoholic name.

In 1847, their father, James Smith, a candymaker, moved the family from St. Armand, Quebec, to Poughkeepsie, New York, and opened a restaurant. It was a bitter winter, and coughs and colds were commonplace. One day, a restaurant customer in need of cash offered James Smith the formula for what he claimed was a highly effective cough remedy. Smith paid five dollars for the recipe, and at home, employing his candymaking skills, he produced a sweet hard medicinal candy.

As Smith’s family and friends caught colds, he dispensed his cough lozenges. By the end of the winter, word of the new remedy had spread to towns along the wind-swept Hudson River. In 1852, a Poughkeepsie newspaper carried the Smiths’ first advertisement: “All afflicted with hoarseness, coughs, or colds should test [the drops’] virtues, which can be done without the least risk.”

Success spawned a wave of imitators: the “Schmitt Brothers”; the “Smythe Sisters”; and even another “Smith Brothers,” in violation of the family’s copyright. In 1866, brothers William and Andrew, realizing the family

needed a distinctive, easily recognizable trademark, decided to use their own stern visages—not on the now-familiar box but on the large glass bowls kept on drugstore counters, from which the drops were dispensed. At that time, most candies were sold from counter jars.

In 1872, the Smith brothers designed the box that bore—and bears—their pictures. The first factory-filled candy package ever developed in America, it launched a trend in merchandising candies and cough drops. A confectioner from Reading, Pennsylvania, William Luden, improved on that packaging a few years later when he introduced his own amber-colored, menthol-flavored Luden’s Cough Drops. Luden’s innovation was to line the box with waxed paper to preserve the lozenges’ freshness and flavor.

As cold sufferers today open the medicine chest for Tylenol, NyQuil, or Contac, in the 1880s millions of Americans with sore throats and coughs reached for drops by the Smith brothers or Luden. William and Andrew Smith acquired the lifelong nicknames “Trade” and “Mark,” for on the cough drop package “trademark” was divided, each half appearing under a brother’s picture. The Smiths lived to see production of their cough drops soar from five pounds to five tons a day.

Suntan Lotion: 1940s, United States

Suntan and sunscreen lotions are modern inventions. The suntanning industry did not really begin until World War II, when the government needed a skin cream to protect GIs stationed in the Pacific from severe sunburns. And, too, the practice of basking in the sun until the body is a golden bronze color is largely a modern phenomenon.

Throughout history, people of many cultures took great pains to avoid skin darkening from sun exposure. Opaque creams and ointments, similar to modern zinc oxide, were used in many Western societies; as was the sun-shielding parasol. Only common field workers acquired suntans; white skin was a sign of high station.

In America, two factors contributed to bringing about the birth of tanning. Until the 1920s, most people, living inland, did not have access to beaches. It was only when railroads began carrying Americans in large numbers to coastal resorts that ocean bathing became a popular pastime. In those days, bathing wear covered so much flesh that suntan preparations would have been pointless. (See “Bathing Suit,” page 321.) Throughout the ’30s, as bathing suits began to reveal increasingly more skin, it became fashionable to bronze that skin, which, in turn, introduced the real risk of burning.

At first, manufacturers did not fully appreciate the potential market for sunning products, especially for sunscreens. The prevailing attitude was that a bather, after acquiring sufficient sun exposure, would move under an umbrella or cover up with clothing. But American soldiers, fighting in the scorching sun of the Philippines, working on aircraft carrier decks, or

stranded on a raft in the Pacific, could not duck into the shade. Thus, in the early 1940s, the government began to experiment with sun-protecting agents.

One of the most effective early agents turned out to be red petrolatum. It is an inert petroleum by-product, the residue that remains after gasoline and home heating oil are extracted from crude oil. Its natural red color, caused by an intrinsic pigment, is what blocks the sun’s burning ultraviolet rays. The Army Air Corps issued red petrolatum to wartime fliers in case they should be downed in the tropics.

One physician who assisted the military in developing the sunscreen was Dr. Benjamin Green. Green believed there was a vast, untapped commercial market for sunning products. After the war, he parlayed the sunscreen technology he had helped develop into a creamy, pure-white suntan lotion scented with the essence of jasmine. The product enabled the user to achieve a copper-colored skin tone, which to Green suggested a name for his line of products. Making its debut on beaches in the 1940s, Coppertone helped to kick off the bronzing of America.

Eye Drops: 3000

B.C

., China

Because of the eye’s extreme sensitivity, eye solutions have always been formulated with the greatest care. One of the earliest recorded eye drops, made from an extract of the mahuang plant, was prepared in China five thousand years ago. Today ophthalmologists know that the active ingredient was ephedrine hydrochloride, which is still used to treat minor eye irritations, especially eyes swollen by allergic reactions.

Early physicians were quick to discover that the only acceptable solvent for eye solutions and compounds was boiled and cooled sterile water. And an added pinch of boric acid powder, a mild antibacterial agent, made the basis of many early remedies for a host of eye infections.

The field of ophthalmology, and the pharmacology of sterile eye solutions, experienced a boom in the mid-1800s. In Germany, Hermann von Helm-holtz published a landmark volume,

Handbook of Physiological Optics

, which debunked many antiquated theories on how the eye functioned. His investigations on eye physiology led him to invent the ophthalmoscope, for examining the eye’s interior, and the ophthalmometer, for measuring the eye’s ability to accommodate to varying distances. By the 1890s, eye care had never been better.

In America at that time, a new addition to the home medicine chest was about to be born. In 1890, Otis Hall, a Spokane, Washington, banker, developed a problem with his vision. He was examining a horse’s broken shoe when the animal’s tail struck him in the right eye, lacerating the cornea. In a matter of days, a painful ulcer developed, and Hall sought treatment from two ophthalmologists, doctors James and George McFatrich, brothers.

Part of Otis Hall’s therapy involved regular use of an eye solution, containing

muriate of berberine, formulated by the brothers. His recovery was so rapid and complete that he felt other people suffering eye ailments should be able to benefit from the preparation. Hall and the McFatriches formed a company to mass-produce one of the first safe and effective commercial eye drop solutions. They brand-named their muriate of berberine by combining the first and last syllables of the chemical name: Murine.

Since then, numerous eye products have entered the medicine chest to combat “tired eyes,” “dryness,” and “redness.” They all contain buffering agents to keep them close to the natural acidity and salinity of human tears. Indeed, some over-the-counter contact lens solutions are labeled “artificial tears.” The saltiness of tears was apparent to even early physicians, who realized that the human eye required, and benefited from, low concentrations of salt. Ophthalmologists like to point out that perhaps the most straightforward evidence for the marine origin of the human species is reflected in this need for the surface of the eye to be continually bathed in salt water.

Dr. Scholl’s Foot Products: 1904, Chicago

It seems fitting that one of America’s premier inventors of corn, callus, and bunion pads began his career as a shoemaker. Even as a teenager on his parents’ Midwestern dairy farm, William Scholl exhibited a fascination with shoes and foot care.

Born in 1882, one of thirteen children, young William spent hours stitching shoes for his large family, employing a sturdy waxed thread of his own design. He demonstrated such skill and ingenuity as the family’s personal cobbler that at age sixteen his parents apprenticed him to a local shoemaker. A year later, he moved to Chicago to work at his trade. It was there, fitting and selling shoes, that William Scholl first realized the extent of the bunions, corns, and fallen arches that plagued his customers. Feet were neglected by their owners, he concluded, and neither physicians nor shoemakers were doing anything about it.

Scholl undertook the task himself.

Employed as a shoe salesman during the day, he worked his way through the Chicago Medical School’s night course. The year he received his medical degree, 1904, the twenty-two-year-old physician patented his first arch support, “Foot-Eazer.” The shoe insert’s popularity would eventually launch an industry in foot care products.

Convinced that a knowledge of proper foot care was essential to selling his support pads, Scholl established a podiatric correspondence course for shoe store clerks. Then he assembled a staff of consultants, who crisscrossed the country delivering medical and public lectures on proper foot maintenance.