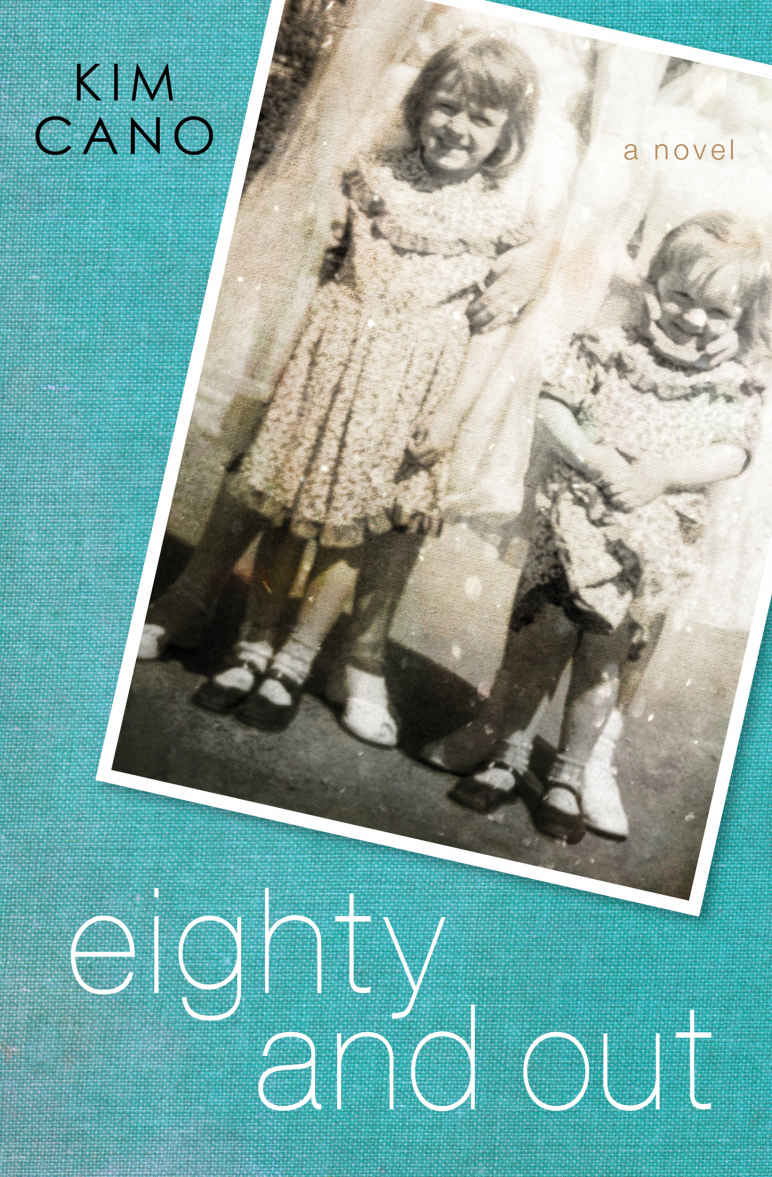

Eighty and Out

Authors: Kim Cano

Eighty and Out

a novel by Kim Cano

Dedication:

For Mom and Aunt Kathy

Back in the fifties, when my younger sister Jeannie and I were kids, we made a pact not to live past age eighty.

We’d seen our fair share of old people doddering around, struggling to make it from point A to point B with their walkers, and decided that wouldn’t happen to us. We’d live life to the fullest and leave this planet with our dignity intact.

As we grew up, the plan dissolved into a silly idea we’d had when we were young and naïve and knew little about life. But now that I’m an older woman, one who has grown wise in her years, I’ve given the pact more thought.

And I’ve decided to keep my end of the bargain.

I was sitting in the alcove under the stairs reading

Young Romance

when I heard my mom call me, but I ignored her because I was at the best part of the story. A few minutes later, I heard my sister’s footsteps growing louder, thumping on the hardwood floor, making it difficult to concentrate.

Jeannie poked her head into my hiding spot. “C’mon, Lou. Mom said we gotta go.”

“Fine.” I groaned, rolling up the magazine to bring along.

I dreaded these trips to the old folks’ home to see Aunt Violet, but I wasn’t allowed to say so since I was only eleven years old. Last time I complained about going, I had my mouth washed out with soap.

We piled into the car and before we’d even left the driveway, Dad was already talking with Mom about his favorite subject: Communism and Senator McCarthy. I tuned out, preferring to stare out the window and watch the neighborhood go by.

Chicago wasn’t very pretty, I decided. It was too plain. Too flat. And the homes all looked the same. When I grew up, I planned to move out west and marry a rancher. I’d have horses and live on acres of land surrounded by mountains. I’d never been out west, but I felt it was my fate.

“You wanna play dolls?” Jeannie asked, interrupting my thoughts.

“I’m reading,” I stated while unrolling my magazine.

Jeannie gave me a look that said, “You’re not reading. You’re looking out the window.” I ignored her and buried my nose between the pages. I hated when she bugged me to play dolls. I wasn’t a little kid anymore.

Shortly after getting immersed in the story, I heard the crunch of gravel under the tires. I looked up and saw the faded green building, and my heart sank. The place was depressing. Even the exterior looked tired.

On the way in, my mom turned to face me. “Remember what I told you,” she said with a stern look.

“I remember.” I nodded.

Jeannie grinned at me, and I almost giggled.

On our last visit, I’d made the mistake of asking, “What’s that awful smell?” I guess I’d said it loudly too, because everyone in the room looked at me: the nurses, several old men and women, my mother. The look she gave me promised the spanking of all spankings once we got home.

I smiled at Jeannie. At least I could get away with that.

As we walked inside, the familiar stench hit my nostrils, and I cringed. I wondered how everyone could be going about their business acting normal, showing no reaction to the nauseating smell. Once we made it to Aunt Violet’s room, Mom opened the door and smiled brightly.

“Hey. Look who’s here to see you,” she said in a sweet voice.

Everyone smiled and waved on cue. We all lined up to give her a hug and a kiss. When it was my turn, I couldn’t decide which was worse, the smell of the old folks’ home or her powdery perfume, applied in layers so thick it lingered in my nostrils long after I pulled away, threatening to suffocate me.

While my parents talked to her about how she was feeling, I gazed at the framed photos on the wall. They were pictures of Aunt Violet and her late husband, Irving, through the years. My favorite was the one of Aunt Violet in her blue sequined gown. She was so elegant and beautiful when she was a ballroom dancer.

I glanced at the old woman who sat on the bed, her snow white hair pinned in place in an attempt at beauty, her skin heavily wrinkled and her hands gnarled. As I stared, she tried to get out of bed and cried out in pain. I jumped at the awful sound.

Mom and Dad rushed to help her while Jeannie and I watched, horrified. Aunt Violet looked frightened and frail. Once she got her footing, Mom helped her shuffle to the restroom.

I looked up at her when she came back in the room on her own. I was certain she would fall. Somehow, she made it back to her bed.

“And how has Miss Louise been lately?” she asked, smiling. “What have you got there?”

I tucked my chin, embarrassed. “A romance comic,” I mumbled.

She nodded approval. “I see. Already learning the ways. You’re growing up so fast, kiddo. And getting so pretty. I’ll bet you’ll have so many suitors wanting to marry you they’ll have to fight to the death to make you their bride.”

I smiled. Aunt Violet had a flair for drama. Mom had said when she was little Aunt Violet used to tell her bedtime stories, but not the kind you read in a book. Aunt Violet made them up. Mom had always looked forward to story time.

Aunt Violet turned her attention to Jeannie. “What’s your doll’s name?” she asked.

Jeannie glanced at me. I nodded toward Aunt Violet. “Tell her,” I whispered.

Jeannie turned back to Aunt Violet. “Jane,” she said, lifting the doll.

Everyone smiled, and the adults resumed their conversation. I pretended to read, but this time I was really eavesdropping. They talked about Aunt Violet’s health and words like rheumatoid arthritis, inflammation levels, and joint destruction filled the small room. I didn’t know what any of it meant, but none of it sounded good, and I was thankful when it was time to go.

Later on, after I’d helped with the dinner dishes, I went outside to play. Some of the neighborhood kids were pitching pennies, so I joined them.

“Where have you been?” Bernice asked.

“Old folks’ home.” She knew better than to ask how it went. I’d already told her how much I disliked going there.

“You wanna play?” she asked, holding up a coin.

“I don’t have anything to lose today,” I said.

Bernice nodded. She was the best at the game, but instead of collecting the loser’s coins, she got paid in candy. She preferred bubble gum, but she’d take marbles, baseball cards, or whatever they’d agreed on beforehand if her opponents didn’t have any.

I watched as each of the players took their shot. Frankie’s penny got pretty close to the wall, but when Bernice threw hers, it hit the brick surface and dropped straight down.

“Damn it,” Frankie cursed. “How do you do it every time?”

Bernice smiled. “Just lucky, I guess.”

The first two boys each handed her a piece of gum. Frankie reluctantly gave Bernice one of his marbles, spat on the ground and walked away.

“He’s such a sore loser,” I said once we were alone.

Bernice shrugged. “You want some gum?”

“Sure.” I took a stick from her, unwrapped it and popped it in my mouth.

We spent the next half hour practicing pitching pennies. She showed me her technique, claiming it was all in the wrist, but I was never able to master it.

It was still light out, but getting late.

“I better get back home and put this away,” Bernice said, holding up the marble and winking. She had a wooden box where she stored her winnings. It was so organized the marbles were separated by color in their own compartments.

“Okay. See you tomorrow.”

I should have gone home too, but I decided to climb my favorite tree instead. It was the one place where no one could disturb me. It’s where I always went when I wanted to be alone.

The sun began to set, so I leaned against a large branch and watched. As the sky turned varying shades of orange and pink, I let myself visit a familiar daydream. Imaginary mountains filled the horizon, and I glanced at them from atop my black horse, Maximilian. We’d just returned from an exhilarating ride, and it was time to put him back in his stall so I could eat dinner with my handsome husband and well-behaved kids.

I heard someone whistle and looked down. There was just enough light left for me to see a colored boy walking down the street by himself.

But he wasn’t alone. The whistle had come from one of the older neighborhood boys, who was silently gesturing for his buddies to follow.

“Shit,” I said in a half-whisper.

I wanted to head home, but I couldn’t climb down because it would attract too much attention. So I waited. When the colored boy turned the corner, the group of white kids took off running after him, so I slid down and dropped to the ground, scraping the palms of my hands on the bark and twisting my ankle in the process.

Shouting erupted in the distance, and I took the opportunity to run away as fast as I could. Fear trumped the pain in my ankle, and I made it home in record time. As I bolted through the front door and slammed it shut behind me, I came face to face with my mom. Her arms were crossed in front of her chest, and she glared at me.

“Do you know what time you’re supposed to be home?” she asked, anger bubbling just beneath the surface of her words.

I looked down. “Before dark,” I mumbled.

“You’re grounded!” she shouted. “Now get to your room.”

I didn’t make eye contact. I just ran past her as quickly as I could in the hopes I might avoid a spanking. I made it to my room unscathed, changed into pajamas and climbed into bed. As I lay there, I wondered what the colored boy was doing walking around all by himself. They had their side of the tracks, and we had ours. And no one ever crossed them.

The next morning, my mom took my romance comics away and handed me a sponge, Ajax, and a bucket and told me to clean the bathroom. I had planned to meet Bernice and go bike riding. Instead, I was stuck doing chores.

I scrubbed and scrubbed the clawfoot tub and was surprised to find out just how much elbow grease it took to clean. You’d think all the dirt would just drain away after every bath. An hour later, I had finished the whole bathroom and stood to examine my work. The room sparkled and smelled fresh, filling me with a sense of accomplishment.

My dad came up beside me. “It’s spotless. Great job,” he said, glancing over his shoulder. He turned back to me. “Here. Take this.” He handed me a Fanny May Pixie from the box Mom had just gotten for her birthday.

“Thanks.” I smiled, and as I did he put his finger to his lips to indicate it was our secret. I nodded, then went to my room and enjoyed the delicious treat, a mixture of caramel and nuts drenched in milk chocolate.

I lay on my bed, fully aware it was only a matter of time before my mom gave me another task, which was her special way of driving home the “you will submit to the rules” message. The rules really weren’t that difficult to follow. My parents were kind and fair. The problem was me. I was headstrong. Where Jeannie listened and behaved like a model child, I did the opposite, and no amount of punishment seemed to alter my behavior.

Jeannie opened the bedroom door, her doll tucked under her arm.

“What’s going on?” I asked.

“Nothing.” She came and sat down next to me. “I’m bored.”

If I weren’t grounded, I would’ve been outside with my friends. I didn’t know what Jeannie did while I was away and mostly didn’t care. But today I felt a kinship with her. “You want to play a game?” I asked.

Her eyes brightened. “Sure. Which one do you want to play?”

“How about Candy Land?” It was her favorite.

Jeannie smiled and went to get it from the hallway closet. An hour later, I was surprised to realize how much I was enjoying playing with my usually annoying sister. I made a mental note to spend more time with her from now on.

Jeannie belched loudly, and we both started laughing. Mom walked in wearing a serious look, which was quickly replaced by a happy face when she saw us enjoying ourselves. I made eye contact with her, and she suppressed her smile just enough to remind me who’s boss.

“Do you want me to clean anything else?” I asked, standing up. I hoped it would make me appear obedient. I wanted her to know she’d won.

“Not right now,” she answered. “I’m going to start lunch, and then we’re going to the store to shop for school supplies.”

When she left, I noticed Jeannie had braided her doll’s hair. I looked at Jeannie’s unruly mane. “How about I braid your hair to match the doll’s?”

Her face lit up. “Okay. Let me grab my brush.”

Jeannie rushed from the room, and after she returned, I spent the next half hour removing the tangles and weaving her hair into an intricate ponytail. “There. Now you and Jane match,” I said as she inspected the finished result in the mirror.

We sat down to eat egg salad sandwiches, and Mom eyed Jeannie. “Your hair looks pretty.”

Jeannie smiled. “Lou did it.”

Mom glanced at me, and I grinned. I could tell she didn’t want to stay mad at me, but she always tried to keep a serious face for a day or two after I’d disobeyed – like that made the punishment stick better or something. She’d grounded me for a week once before, when I’d slipped up and said the wrong thing at the nursing home, but that was different. She wasn’t just angry that time, she was embarrassed. Mortified was the word she’d used.

On the way to the store, we passed Bernice and some of the neighborhood kids. They were having fun playing hopscotch. I wished I could join them, and realized if I listened to my parents more often, I wouldn’t suffer so much.

“Which notebook do you prefer? Blue or green?” Mom asked as she held up one of each.

“Doesn’t matter.” I had an opinion on everything I wasn’t supposed to have an opinion on, but when asked about topics relevant to my little world, I couldn’t care less.

I rounded the corner to look at the comic books while Mom and Jeannie continued shopping. A teenage boy stood reading a magazine. I recognized him as one of the boys I’d seen following the colored kid. When I reached for

Young Romance

, I noticed his eye was black and blue.

He leered at me. “Beat it. I’m reading here,” he said.

I put the comic back on the rack and left, irritated he had bossed me around and secretly delighted he’d been smacked in the face. They might have beaten up the colored boy, but it looked like he had gotten at least one good punch in.

I didn’t know what all the fuss was about over people’s skin color. It seemed silly, and it wasn’t like any of us had a choice in the matter. Conveniently, the subject came up at the dinner table that night.

“They’re coming to the school this year,” Dad said, sounding concerned.

Mom sighed. “Well, there’s nothing we can do about it.”

“We could send the kids to private school.”

“That costs money,” Mom said. Dad frowned at that.

I wanted to say I didn’t care and not to worry, but I kept my mouth shut. I continued eating my meal in silence while Jeannie played with her food, oblivious to their concerns.

A few days later, my confinement ended, and I was allowed to leave the house. Dad had given me a watch so I could keep better track of time, but in my rush to get outdoors, I’d forgotten to put it on.

The hot wind tousled my hair as I rode my bike to the park. I usually wore it in a ponytail so it wouldn’t get messy, but today I left it loose, a fitting symbol of my newfound freedom. On my way there, I kept my eyes peeled for Bernice. I didn’t see her in any of the usual places, and when I got to the park, she wasn’t there either.

Oddly enough, no one was there. I had the place all to myself.

I hopped off my bike and ran to the swing set. After I’d gotten situated in the center swing, I grabbed hold of the heavy chains and pushed off the ground. I pumped my legs to propel myself upwards, and the higher I climbed, the more exhilarated I felt. It was almost as if I could touch the sky. I leaned back and let my legs go limp, gliding back and forth like a human pendulum.

When Mom was around, she wouldn’t let me do it. She claimed it was too dangerous, and I could get hurt. But it was my favorite thing to do.

After I’d taken a few more turns, I was ready to leave. I was just about to get on my bike when I saw Bernice. She put her hands on her hips. “Let me guess. You were grounded.”

“That would be correct,” I replied as I set the bike against the kickstand. I said it without shame even though I knew it wasn’t something to be proud of. There were lots of kids who thought that kind of thing was cool, but Bernice wasn’t one of them.

“Well, you missed some neighborhood gossip,” she said as she sat on the park bench.

“Yeah? What’s that?” I sat beside her.

“Frankie’s older brother got into a fight with a colored boy who was walking around here the other night. I guess a group of older kids chased him back to his side of town, but before things ended there was a fight, and the colored boy clocked him good.”

I thought of the boy at the store. Bernice and I had never discussed race, and I wasn’t sure how she felt about the situation, so I didn’t voice my opinion. With my parents I was abrupt, often to my own detriment, but I tended to be more careful when I spoke with Bernice.

“I heard they’re going to be at school with us this year,” I said, giving no hint of my feelings on the matter.

She stared at the other side of the playground. “My mom was talking to my grandma about it on the phone the other night. They don’t think it’s a good thing.”

I raised an eyebrow.

“My family isn’t prejudiced or anything,” she said. “They just think there will be trouble at school. And you know my parents. It’s all about learning with them. They don’t want anything to interfere with that.”

I thought about my dad’s comment, that he’d like to send us to private school but couldn’t because it was too expensive. I was going to tell her about it but decided not to since her family had more money than ours. It wasn’t like they were rich. I mean, they lived in our neighborhood and all, but they definitely had more. Bernice told me a story once about her uncle being a successful author, and that he had left them some money when he died.

“Well, let’s hope there won’t be any trouble then,” I said.

Bernice sighed. “If the rumors I’ve been hearing are true, I don’t think hope will make a difference.”