Essex Land Girls (5 page)

Authors: Dee Gordon

The officers had horses and the men had mules … which were fed from troughs, to the accompaniment of a bugle playing:

Oh come to the stable you men that are able

And walk to your horses and give them some corn.

Other unforgettable incidents include the day Olive came back from lunch at her billet and an officer spoke to her, but she had a mouthful of toffee and couldn’t answer him back, and the day she lost one farming job because she went to church with the stable boy. Then there was the time she was picking currants and saw her first German aeroplane coming over from the direction of Southend, falling down in her haste to get away. This was one of the few reminders of the war going on around her – another was seeing a Zeppelin coming down over Billericay in 1916. But her memories are mainly of less alarming times.

The

Chelmsford Chronicle

continued to report meetings of the EWWAA in May 1919, with Lady Petre still at the helm. A member of the Executive Committee confirmed that the ‘woman on the land’ was likely to remain in Essex as ‘a blessing of peace’. The high standards required by the WLA during the First World War were stressed, with 1,500 girls being interviewed in Essex during the previous two years and just 535 accepted, and another 500 girls had been trained up, meaning that 300 had been ‘imported’ from other counties. The average wage had inched its way up to 27

s

8¼

d

, with billets being charged at 16

s

11

d

. During the preceding year, sixty-two girls had been tested for efficiency certificates, with twelve passing Class A and thirty-six passing Class B.

Members of the WLA in Essex were presented with ‘Good Service’ ribbons early in 1919, soon after the end of the First World War. Such awards revealed satisfactory evidence regarding their work and conduct, sourced from their employers who had been asked questions regarding their punctuality, behaviour and industry. Comments received from employers were satisfyingly complimentary – ‘could not wish for a better’, ‘cannot speak too highly’ and even, ‘better than any man’.

At the end of 1919 (29 November), Princess Mary presented a number of Land Girls with the Distinguished Service Bar (DSB), popularly known as the ‘Land Girls’ VC’. The princess attended a meeting at Shire Hall in Chelmsford where a resolution, invoked by Lady Petre among others, was passed to approve the formation of an Essex branch of the National Association of Landswomen following the demobilisation of the WLA. Recipients of the DSB included ‘Miss C. Capper’ and ‘Miss G. Chapman’, the latter described as an Essex Land Girl who had been decorated for more than one ‘plucky deed’ (the terminology of the

Essex Newsman

). On one occasion, she had broken a bone in her foot and injured a rib in an accident, but insisted upon finishing her milk round as no other workers were available. On another, when in charge of a hay wagon, a horse took fright, reared and bolted, but she managed to hold on to his head until he came to a standstill. Two other members of the WLA, Miss M. Skeats and Miss G. Tyler, were specially invited to attend the subsequent supper and concert as a thank you for their long service and good record.

At Tiptree Jam Museum, a rhyme has been archived, dedicated to ‘The Lady Carter’ delivering fruit to the factory. It is adapted from Thomas Macaulay’s

Lays of Ancient Rome

,

and is of particular interest because of its references during the First World War to ‘young maids’ reaping the harvests of East Anglia, and to ‘strapping wenches’ stirring the ‘foaming vats at Tiptree’. Whether this was a WLA recruit is, of course, impossible to establish without a name, but she is certainly a contender.

Another poem was quoted in the

Essex Newsman

on 6 December 1919, entitled ‘Goodbye Girls’. This is quoted in part, and is a rather touching, though anonymous, appreciation of the work done by ‘Rose’, a WLA member:

No other Rose is half so sweet

As she who milked our cow;

I fancy still I hear her feet –

I would she were here now.

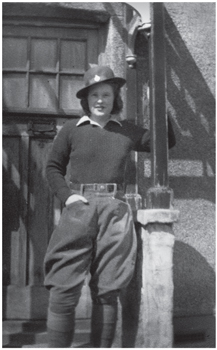

‘The Lady Carter’, as she was known. An anonymous Land Girl at Tiptree Fruit Farm during the First World War. (Courtesy of Tiptree Museum)

The Second World War in Essex

The Growth of the WLA in Essex: Preparations

In 1939, the UK was importing 60 per cent of its food from overseas. More land was needed for food production, and local War Agricultural Executive Committees had been established before the war to find and utilise the great swathes of Essex countryside massed with thorn bushes and untrimmed hedges the size of small copses. Members of the committee visited farms and decided on which fields needed ploughing, with the farmers being paid a grant of £2 per acre as compensation. Inefficient farmers were threatened with eviction, so there was certainly pressure on them to produce the goods.

This was also the very beginning of mechanised farming, an essential requirement for some of the heavy clay lands of Essex. Mechanisation slowly helped to boost food production, turning the eastern counties into the ‘granary of England’ with 60,000 additional acres in Essex identified for ploughing by the Ministry of Agriculture.

However, between 1921 and 1939, over 20 per cent of farm workers left their jobs in Essex, leaving insufficient labour to provide the increased production that was now necessary. All male farm workers, shepherds, pig men, cattle men and greenhouse workers aged 21 and over were called up.

Thirteen War Ag committees were quickly established in Essex, additionally involved in recruitment, enlistment and administration. Lady Gertrude Denman accepted the role of honorary director of the WLA, with her magnificent home in West Sussex as the national headquarters, initiating a recruitment drive after the official formation of the new WLA in June 1939. This meant that, by September, when the call came for action, 1,000 volunteers were ready countrywide for immediate employment. The revamped Women’s Timber Corps followed in April 1942. Even the BBC’s Home Service was involved in recruiting, with broadcasts during the

Farming Today

programme.

It seems that Lady Denman personally chose women to chair the county committees, often women she knew through the Women’s Institute, having been the WI’s first national chairman. The committee members were all unpaid, and all chosen for their knowledge of country life and local conditions. Mrs R.E. Solly-Flood was appointed the county secretary for Essex, based at the county headquarters at the Institute of Agriculture, Writtle, near Chelmsford; and the county chairman was Olive Tritton from Finchingfield. The WLA was a voluntary organisation for the first two years of its re-formation, with civilians ‘employed’ by either the County War Agricultural Executive Committee (the War Ag), which housed them and arranged transport, or employed directly by farmers. Queen Elizabeth (later the Queen Mother) became the WLA’s patron in 1941.

Britain, unlike Germany, introduced conscription of women in 1941 for single women aged between 20 and 30, then dropped the age to 19 – the first nation in modern times to do so. (There were exemptions for pregnant women and those with children.) Women were then obliged to choose between one of the women’s auxiliary services, the civil defence, or the Land Army, with some civilian employments such as munition workers also available. A total of 17,000 chose the WLA at the outbreak of war, with as many as 80,000 joining up before its end. The number in Essex grew from 124 in 1939 (as milkers, tractor drivers, poultry girls and farmhands – plus another 160 on private farms or in training) to a peak of nearly 4,000 in the county, only just behind Yorkshire and Kent.

Girls in the WLA could work with animals, with crops, or could volunteer for training in pest extermination. There was also the option of the Timber Corps, which could involve working in saw mills, cultivating new trees, and felling trees for road blocks, ladders, telegraph poles or pit props, all of which were in short supply. Although Essex, as one of the coastal counties, was subject to the threat of air attack, this rarely seems to have been a deterrent!

The Land Girl

was launched in April 1940, following the success of

The Landswoman

during the First World War. A few of the Essex Land Girls mentioned this, but as it cost 3

d

perhaps its purchase was not a priority, although it was a useful source of advice and information. (It also produced records of recruiting numbers, county news and a drive to raise funds for their very own Spitfire, a big ask, given that one such aircraft had a price tag at the time of around £5,000!)

Parental pressure could take a hand here.

Ellen Brown

’s dad ‘was not keen on my joining the other auxiliary services’ but okayed her application for the WLA because ‘he didn’t think I’d pass the medical’!

Edna Green

’s parents had similar concerns, with ‘strong doubts as to whether I could exist without the town life in which I had grown up’ in urban Romford. She joined the WLA later than most, at the end of the war, but was concerned that she would miss ‘the comforts of home, Mum’s cooking … and I knew that I would miss my elder sister terribly, but my mind was made up … I knew I had to get away, for better or worse. I had made a decision and I intended to see it through.’

Much earlier, at the outbreak of war,

Joyce Willsher

was working in the Kursaal at Southend-on-Sea when the entertainment venue had been commandeered to make army uniforms. Although she and her friend Lorna ‘enjoyed putting little notes of encouragement in the pockets of the uniforms, we decided we could do more’, and this prompted them to choose the WLA because the headquarters at Writtle was ‘convenient’ enough for them to make initial enquiries.

Mary Page

was also concerned about what was happening to her country, after experiencing air raids over Romford, and this was ‘the spur to my joining the Land Army’.

Edna Green (née Mead) in full uniform. (Courtesy of Braintree District Museum Trust)

A sense of duty also came into play for

Elsie Haysman

, who was ‘doing what my mum wanted. I felt an obligation as the eldest daughter.’ What she really wanted, however, was ‘to join the navy. My dad was a sailor.’

Having started the war in ‘a munitions factory in Chelmsford’ but ‘without the educational requirements’ to fulfil that same ‘dream of joining the WRNS [Women’s Royal Naval Service]’,

Irene Verlander

, then 19 years old, eventually settled for the WLA, ‘recommended by my friend Eva’.

Rita Hoy

had already been ‘doing something of national importance’, in helping out at Ladygrove Woods near Writtle, mainly in the office, but getting her hands dirty by ‘organising the haulage of the pit props for their journey to Chelmsford Railway Goods Yard … I helped with peeling the bark, stacking the pit props … getting very black and hot.’ As she enjoyed the physical work more than the office work, she asked for a change, having heard about a ‘new venture, the Women’s Timber Corps’. This was a choice she made with open eyes, unlike some.

Although

Vicky Phillips

was in a reserved occupation with a bank and had been evacuated from Southend to Surrey at the outbreak of war, she wanted ‘to work outdoors, and preferably with horses’. So the WLA seemed the ‘right choice’ for her.

A love of gardening was what attracted

Dorothy Jennings

from Stratford, whose dad grew the family’s vegetables, whereas

Joyce Theobald

just wanted to get away from family disputes at home in London.

There were others who were simply attracted by the advertising.

Doreen Morey

from Poplar, East London, ‘saw the WLA recruiting office in Oxford Street and I was attracted by the pictures in the office and by the uniform, so I volunteered. I liked the idea of driving tractors and feeding chickens.’ An ‘attractive poster of a Land Army girl with a yoke’ caught the eye of

Florence Rawlings

from the East End, whose war experiences up until then had been pretty unpleasant ‘with the St John’s Ambulance and East Ham Hospital’ – that poster offered a whole new world to such as her. Another East Ender,

Barbara Rix

from Leyton, had a different reason: ‘Because I could join at 17, and I didn’t want to wait any longer’ (this was 1943).