Essex Land Girls (3 page)

Authors: Dee Gordon

There is an interesting reference to the opening of a Girls’ Friendly Society hostel in ‘Essex Girls in War Time’, printed in the

Essex Review

during the First World War (Volume 27, 1918–19). Written by Revd F.D. Pierce, it describes the hostel as being ‘first for munition workers but open now to receive land workers, the first hostel in England for land workers’. The honorary secretary of the Girls’ Friendly Society War Time Fund was Miss Read, of Theydon Bois.

One Land Girl (G.L. Andrews) is mentioned in the March 1918 issue of

The Landswoman.

She is said to be working at White’s Farm in ‘Lamdon’ in Essex, although this is probably a misspelling of Laindon, and had written in response to the Correspondence Club initiative. She is among a list of ‘girls who want letters’, so White’s must have been a lonely spot at the time.

In January 1916, George Edwards, leader of the Farm Workers’ Union, put an appeal in the East Anglian dailies, asking for the women of Essex, Norfolk and Suffolk to fill the gap left by the departure of half the Essex agricultural workers.

Even earlier on in the war, dairy farmers were being encouraged to release their male milkers and train women to take their place. The Board of Agriculture wanted to establish training for women in farm work in each county, with the board bearing the cost, so Lady Petre, Miss Courtauld (who described herself as a woman farmer) and others were appointed to discuss the establishment of this facility with the Agricultural Education Committee. Miss Courtauld was in favour of a six-week training course which had worked for some of the ‘pupils’ she had working for her – girls who, she reported at an April 1916 EWWAA meeting in Chelmsford, ‘had done nothing before, and had been waited upon by servants’ but who would now ‘get up at five o’clock and milk, take out the horses and bring in the crops’.

By 1912, the East Anglian Institute of Agriculture had been established in Chelmsford, and this was Lady Petre’s suggestion for a venue for some training to take place. She had started a milking school at Thorndon Hall, her country home in Brentwood in 1916, although this was initially aimed at children who could then help out at local farms. With her help, 100 women had been trained, mainly as milkers, by mid-1917, with sixty still in training, but there were over 6,000 working on the land in Essex just months later (not all members of the WLA) whether trained or not.

Farmers were beginning to promise to train up members of the WLA, and training at the Institute of Agriculture was stepped up to include courses in rabbit catching, rat catching, thatching and coppicing, although of course there were far more training opportunities for men than for women. One Essex farm, in the village of Willingale in Epping Forest, also offered induction and training courses, with wooden cows available with rubber teats as one of its facilities. In the East Anglian Film Archive there is a 1916 newsreel featuring WLA girls working in the fields at Willingale with long dresses and bonnets, some clearing weeds and undergrowth, some feeding piglets and some hoeing between rows of potatoes. (Interestingly, this newsreel also features a horse, wounded at the Battle of Loos, being watered and then ridden side-saddle back to work.) Some farmers came forward early on, with Mr A.J. Dean of Southend offering the EWWAA a large farmhouse and grounds free of rent and taxes for ‘use in the instruction of women’ (

Chelmsford Chronicle

, 17 March 1916).

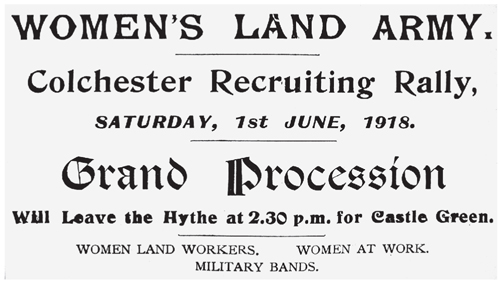

Recruitment rallies took place around the county, and were reported in local newspapers.

East Coast Illustrated & Clacton News

advertised a rally at Colchester on 1 June 1918, and this was reported in the

Chelmsford Chronicle

,

including details of a march-past. The mayor and mayoress were in attendance, with other local notables. One of these, the Hon. Mrs Alfred Lyttelton, said that farmers had come to recognise the value of women workers during the past year. She pointed out that Essex was ‘the greatest fighting county in England’ and that ‘Essex women would not lag behind in backing up their brothers who were fighting in France’.

The Women’s Land Army Rally in Colchester, May 1918, as advertised in the

East Coast Illustrated & Clacton News.

(Courtesy of Roger Kennell)

The same month there was a recruiting rally in Brentwood organised by the indomitable Lady Petre, with decorated farm vehicles and carts parading through the town, and the High Street was decorated to ‘resemble the scene of an old English Mayday fete’ (

Chelmsford Chronicle

). The women were dressed in their brightest clothes to invite others to come forward and beat the Germans ‘by growing more and more food’. Speeches were made by Miss Courtauld, emphasising the ‘attractiveness of the work’; Mrs Hicks, who said ‘she had been doing land work for eighteen months and loved it’; and by JP George Hammond. Mr Hammond said that ‘agriculture had been raised from its previous lowly position, and was now recognised as being not only important and valuable work but a necessity if we were to win the war’. He appealed to all who could to ‘come forward and do this work’ – and a number were duly enrolled.

A month later, there was a public meeting in Valentine’s Park, Ilford, as part of the Essex recruiting campaign, and all such recruitment drives were apparently successful.

Even more high profile was a highly organised demonstration by the WLA at Chelmsford on 22 June 1918, with accompanying bands of the Essex Volunteer Regiment and the local King’s Royal Rifle Corps. Members and ‘trainers’ (according to the

Chelmsford Chronicle

) took part in uniform, led by group leader Miss Turner on horseback, bearing the Union Jack as the standard. Wagons, decorated carts and animals, all led by women, made up the procession, together with other agricultural exhibits. Recruitment was still ongoing, following the prospect of the best harvest for twenty years, with more women workers needed.

Mr Thompson JP announced that women had already shown ‘the most splendid devotion’ and he felt that those not already serving their country would ‘answer the clarion cry’ to help to win the war. ‘The exigencies of the times demand not only the help of every able-bodied man and every able-bodied lad, but the help also of every able-bodied woman and girl.’ It seems that the 35,000 army men promised to help the farmers were ‘not now forthcoming’ and so the call came to the women of Essex. ‘Who could refuse to fight in what was really our second line of defence – the food line?’

One land worker, May Kemble, also spoke out on the subject of the world shortage of food. She produced a cheer from the crowd with her message that ‘England alone … had not only maintained her pre-war production but had increased it’. Although unable to offer wealth, she spoke of the ‘abiding happiness which came of duty done and joy in the work itself’. No girl who had experience of the health and freedom of the land would go back to the cooped-up city life. Of course there was the winter mud and rain, but women did not want ‘soft’ jobs while the men were risking their lives (more cheers) and, after seeing the pictures of the Somme battle, there would be ‘no more grousing about mud at home’.

A further speech from the Hon. E.G. Strutt referred to the national loss of 350,000 men from agriculture as a result of the war, and the need for ‘women of Essex to come forward and help them … women could do much more work than people realised [and] it was a job that had to be taken seriously, not like tossing hay or being photographed’. This produced laughter from the assembled crowd outside Shire Hall. Mr Strutt emphasised the benefits that women would find with regard to health, happiness, and the ‘feeling of a good conscience … learning a business which might be most useful in after life’. He paid a tribute to the women already at work on the land, and mentioned ‘one village on the borders of Essex from which before the war only two women ever went to work upon the land. At this moment there were sixty-two women from that village working 48 hours a week.’ It seemed that in his own village, there were now twenty women who could milk a cow ‘grandly’ and one woman producing a ton of cheese every week. ‘Would the women of Chelmsford go to help them and have some?’ This must have been tempting, given that rationing had kicked in from February!

A recruiting officer for the WLA, Gwynne Jones, followed up with an eloquent speech offering women ‘a magnificent opportunity of creating something worth handing over to the men’. This drew cries of ‘hear, hear’ and she was also applauded for her appeal to women to ‘come out and make sure that we were not beaten to our knees because the women were too soft, or too stupid and indifferent’.

Miss Courtauld of Colne Engaine (a tiny village near Earls Colne) said her bailiff had enlisted at the outbreak of war and she at once took his place:

At first, the women were told to sit at home and knit [laughter] but now they were glad to take the place of the man and really be of use to their country … There was no bread sweeter than that earned by a hard day’s work, and there was no work that helped one to bear sorrow and trouble so much as work on the land. They must keep the home fires burning, but there was no need to sit over them all day with a book or even a bit of knitting.

One of the last appeals was made by Captain Warne of the Forage Department, who announced that he could do with ‘800 women’ to set that number of men free for France. The Women’s Department of National Service was also calling for recruits to work in timber measuring.

Trained workers were appearing all over the county – which was much more rural then than now of course. In the High Street at Great Leighs, the Reverend Andrew Clark spotted a couple of girls in uniform in 1916, and wrote in his diary of them as ‘swaggering’ and ‘dressed in riding breeches, like troopers … carrying shortish rattans such as grooms might have’. He later wrote of farmers who had ‘vowed they never would have women land workers being compelled to employ them. They do not think much of their work but they cannot get on without it.’ By 1919, he was writing of it being ‘mostly women who were at work in the fields, chiefly weeding beans … the men, who had been brought up to it, were content to be idle and to go into Braintree and draw unemployment pay’.(!)

In the April 1918 issue of

The Landswoman

there was an article written by Lady Petre, in her role as the President of the Essex County Federation of Women Institutes. This was a detailed account regarding ‘Boot-Mending At Home’, perhaps rather unexpectedly given the source, but proclaiming that ‘it should be as natural to do this at home as to darn stockings’.

The

Illustrated War News

of 30 August 1916 refers to the Hon. Edward Gerald Strutt, brother of Lord Rayleigh, training girls and women ‘doing men’s work on Lord Rayleigh’s farms in Essex. They are billeted in Terling, and work in overalls and breeches and soft felt hats.’ The accompanying photographs show some ‘putting the corn up in stooks’ and others, described as ‘girl farmers’, feeding pigs at Ringer’s Farm ‘in place of men called to the colours’.

A week earlier, the same newspaper had images of ‘women-workers on the land in time of harvest’ in Essex. One image shows a ‘woman-worker … riding, man-fashion, one fine horse and leading another’. The second shows:

… farmer’s daughter, Miss Luke [in trailing skirt and bonnet], herself driving the machine, and a soldier in khaki is at the side. Mr Luke of Aldboro’ Hatch Farm, Essex, has arranged for a number of soldier helpers. His daughter is an expert reaper and is shown cutting a large field of wheat. The versatility of the woman-workers as elicited by the war is little less than wonderful.

Although the soldier featured in the image is a British soldier, there are reports in the

Illustrated War News

that the summer of 1917 saw German prisoners loading hay on an Essex farm under guard and hoeing a field in Essex, but whether these prisoners worked alongside Land Girls is not specified.

In the summer of 1918, the

Ilford Guardian

featured an article describing the Land Girls locally as ‘doing every kind of work from thatching to mole catching’. The article pointed out that most enrolled for six months, when they were sent straight to farms, or for one year in which case they received six weeks’ free training, applicable to the agricultural and timber-cutting sections of the Land Army. Those who wished to do forage work (under the control of the War Office) ‘must sign on for twelve months’. The girls were described as ‘doing excellent work in sending hay to the front, and the usefulness of the timber gangs can hardly be exaggerated’. At the time, however, food shortages placed special stress on the agricultural section, which included ‘dairy work, milking, the care of all kinds of stock and poultry, market gardening, tractor ploughing and every kind of field work’.

Among the impressive collection of photographs at Mersea Museum is one of uniformed Land Girls at Bocking Hall in Mersea working for ‘seed growers’, around

1918. The theory is that the WLA here recruited local girls rather than bringing in ‘outsiders’, backed up by the fact that many of the surnames of those identified are familiar locally, both before and after the photograph.