Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber (54 page)

Read Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber Online

Authors: Geoffrey Block

For his remaining eight years Loesser was unable to bring a work to Broadway.

Pleasures and Palaces

, a show about Catherine the Great, closed out of town in 1965, and Loesser died before he could fully complete and begin to try out

Señor Discretion

. But Loesser’s legacy remains large, and in his thirteen years on the Broadway stage he fared far better than Runyon’s 6–5 odds against. As Loesser’s revivals have shown, Broadway audiences, collapsing under the weight of musical spectacles, are reveling in the musicals of Loesser, the composer-lyricist who continues to give audiences and even musical and theater historians and critics so much to laugh (and cry) about and so little to sneeze at.

MY FAIR LADY

From

Pygmalion

to Cinderella

M

y Fair Lady

was without doubt the most popularly successful musical of its era. Before the close of its spectacular run of 2,717 performances from 1956 to 1962 it had comfortably surpassed

Oklahoma!

’s previous record of 2,248.

1

And unlike the ephemeral success of the wartime Broadway heroines depicted in

Lady in the Dark

and

One Touch of Venus

, librettist-lyricist Alan Jay Lerner’s and composer Frederick “Fritz” Loewe’s fair lady went on to age phenomenally well. Most remarkably, over eighteen million cast albums were sold and profits from the staged performances, albums, and 1964 film came to the then-astronomical figure of $800 million. Critically successful revivals followed in 1975 and 1981, the latter with Rex Harrison (Henry Higgins) and Cathleen Nesbitt (Mrs. Higgins) reclaiming their original Broadway roles. In 1993 the work returned once again, this time with television miniseries superstar Richard Chamberlain as Higgins, newcomer Melissa Errico as Eliza, and Julian Holloway playing Alfred P. Doolittle, the role his father, Stanley, created on Broadway on March 15, 1956.

As with most of the musicals under scrutiny in the present survey, the popular and financial success of

My Fair Lady

was and continues to be matched by critical acclaim. Walter Kerr of the

Herald Tribune

told his readers: “Don’t bother to finish reading this review now. You’d better sit down and send for those tickets to

My Fair Lady

.”

2

William Hawkins of the

World-Telegram & Sun

wrote that the show “prances into that rare class of great musicals” and that “quite simply, it has everything,” providing “a legendary

evening” with songs that “are likely to be unforgettable.”

3

In what may be the highest tribute paid to the show, Harrison reported that “Cole Porter reserved himself a seat once a week for the entire run.”

4

Opening night critics immediately recognized that

My Fair Lady

fully measured up to the Rodgers and Hammerstein model of an integrated musical. As Robert Coleman of the

Daily Mirror

wrote: “The Lerner-Loewe songs are not only delightful, they advance the action as well. They are ever so much more than interpolations, or interruptions. They are a most important and integrated element in about as perfect an entertainment as the most fastidious playgoer could demand…. A new landmark in the genre fathered by Rodgers and Hammerstein. A terrific show!”

5

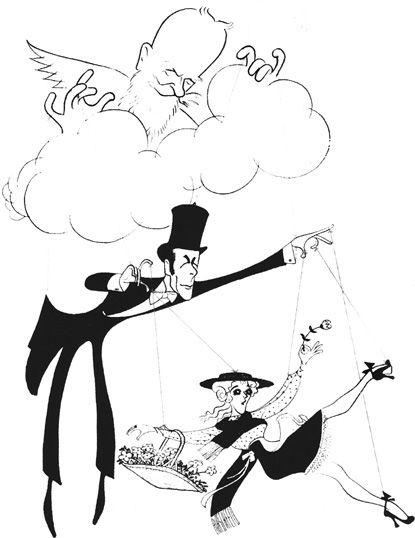

My Fair Lady

. George Bernard Shaw and his puppets, Rex Harrison and Julie Andrews (1956). © AL HIRSCHFELD. Reproduced by arrangement with Hirschfeld’s exclusive representative, the MARGO FEIDEN GALLERIES LTD., NEW YORK.

WWW.ALHIRSCHFELD.COM

Many early critics noted the skill and appropriateness of the adaptation from George Bernard Shaw’s

Pygmalion

(1912). For

Daily News

reviewer John Chapman, Lerner and Loewe “have written much the way Shaw must have done had he been a musician instead of a music critic.”

6

Hawkins wrote that “the famed

Pygmalion

has been used with such artfulness and taste, such vigorous reverence, that it springs freshly to life all over again.”

7

And even though Brooks Atkinson of the

New York Times

added the somewhat condescending “basic observation” that “Shaw’s crackling mind is still the genius of

My Fair Lady

,” he concluded his rave of this “wonderful show” by endorsing the work on its own merits: “To Shaw’s agile intelligence it adds the warmth, loveliness, and excitement of a memorable theatre frolic.”

8

Lerner (1918–1986) and Loewe (1901–1988) met fortuitously at New York’s Lambs Club in 1942. Before he began to match wits with Loewe, Lerner’s marginal writing experience had consisted of lyrics to two Hasty Pudding musicals at Harvard and a few radio scripts. Shortly after their meeting Loewe asked Lerner to help revise

Great Lady

, a musical that had previously met its rapid Broadway demise in 1938. The team inauspiciously inaugurated their Broadway collaboration with two now-forgotten flops,

What’s Up

? (1943) and

The Day before Spring

(1945).

Documentation for the years before Loewe arrived in the United States in 1924 is sporadic and unreliable, and most of the frequently circulated “facts” about the European years—for example, that Loewe studied with Weill’s teacher, Ferruccio Busoni—were circulated by Loewe himself and cannot be independently confirmed. Sources even disagree about the year and city of his birth, and the most reliable fact about his early years is that his father was the famous singer Edmund Loewe, who debuted as Prince Danilo in the Berlin production of Lehár’s

The Merry Widow

and performed the lead in Oscar Straus’s first and only Shaw adaptation,

The Chocolate Soldier

.

9

As Loewe would have us believe, young Fritz was a child prodigy who began to compose at the age of seven and who at age thirteen became the youngest pianist to have appeared with the Berlin Philharmonic. None of this can be verified. Lerner and Loewe biographer Gene Lees also questions Loewe’s frequently reported claim to have written a song, “Katrina,” that managed to sell two million copies.

10

Loewe’s early years in America remain similarly obscure. After a decade of often extremely odd jobs, including professional boxing, gold prospecting, delivering mail on horseback, and

cow punching, Loewe broke into show business when one of his songs was interpolated in the nonmusical

Petticoat Fever

by operetta star Dennis King. Another Loewe song was interpolated in

The Illustrators Show

(1936).

11

The

Great Lady

fiasco (twenty performances) occurred two years later.

After their early Broadway failures, Lerner and Loewe produced their first successful Rodgers and Hammerstein–type musical on their third Broadway try,

Brigadoon

(1947), a romantic tale of a Scottish village that awakens from a deep sleep once every hundred years. By the end of the musical, the town offers a permanent home to a formerly jaded American who discovers the meaning of life and love (and some effective ersatz-Scottish music) within its timeless borders. The following year Lerner wrote the book and lyrics for the first of many musicals without Loewe, the modestly successful and rarely revived avant-garde “concept musical”

Love Life

(with music by Weill). Lerner and Loewe’s next collaboration, the occasionally revived

Paint Your Wagon

(1951) was less than a hit on its first run. Also in 1951 Lerner without Loewe wrote the Academy Award–winning screenplay for

An American in Paris

, which featured the music and lyrics of George and Ira Gershwin. By 1952 Lerner, reunited with Loewe, was ready to tackle Shaw.

and

Pygmalion

It may seem inevitable that someone would have set

Pygmalion

, especially when considering the apparent ease with which Lerner and Loewe adapted Shaw’s famous play for the musical stage. In fact, much conspired against any musical setting of a Shaw play for the last forty years of the transplanted Irishman’s long and productive life. The main obstacle until Shaw’s death in 1950 was the playwright himself, who, after enduring what he considered to be a travesty of

Arms and the Man

in Straus’s

The Chocolate Soldier

(1910), wrote to Theatre Guild producer Theresa Helburn in 1939 that “nothing will ever induce me to allow any other play of mine to be degraded into an operetta or set to any music except its own.”

12

As early as 1921, seven years after the English premiere of his play, Shaw aggressively thwarted an attempt by Lehár to secure the rights to

Pygmalion

: “a Pygmalion operetta is quite out of the question.”

13

As late as 1948 Shaw was rejecting offers to musicalize

Pygmalion

, and in response to a request from Gertrude Lawrence (the original heroine of

Lady in the Dark

) he offered his last word on the subject: “My decision as to

Pygmalion

is final: let me hear no more about it. This is final.”

14

Much of our information on the genesis of

My Fair Lady

comes from Lerner’s engagingly written autobiography,

The Street Where I Live

(1978), more than one hundred pages of which are devoted to the compositional genesis, casting, and production history of their Shaw adaptation.

15

Additionally, Loewe’s holograph piano-vocal score manuscripts in the Music Division of the Library of Congress offer a fascinating glimpse into some later details of the compositional process of the songs.

From Lerner we learn that after two or three weeks of intensive discussion and planning in 1952 the team’s first tussle with the musicalization of Shaw’s play had produced only discouragement. Part of the problem was that the reverence Lerner and Loewe held for Shaw’s play precluded a drastic overhaul. Equally problematic, their respect for the Rodgers and Hammerstein model initially prompted Lerner and Loewe to find an appropriate place for a choral ensemble as well as a secondary love story. While a chorus could be contrived with relative ease, it was more difficult to get around the second problem: Shaw’s play “had one story and one story only,” and the central plot of

Pygmalion

, “although Shaw called it a romance, is a non-love story.”

16

In a chance meeting with Hammerstein, the great librettist-lyricist told Lerner, “It can’t be done…. Dick [Rodgers] and I worked on it for over a year and gave it up.”

17

Lerner and Loewe returned to their adaptation of Shaw two years later optimistic that a Shavian musical would be possible. As Lerner explains:

By 1954 it no longer seemed essential that a musical have a subplot, nor that there be an ever-present ensemble filling the air with high C’s and flying limbs. In other words, some of the obstacles that had stood in the way of converting Pygmalion into a musical had simply been removed by a changing style…. As Fritz and I talked and talked, we gradually began to realize that the way to convert

Pygmalion

to a musical did not require the addition of any new characters…. We could do

Pygmalion

simply by doing

Pygmalion

following the screenplay [of the 1938 film as altered by director Gabriel Pascal] more than the [stage] play and adding the action that took place between the acts of the play.

18

Instead of placing Higgins as a professor of phonetics in a university setting in order to generate the need for a chorus of students, Professor Higgins used his home as his laboratory and a chorus composed of his servants now sufficed. Since the move from a tea party at the home of Higgins’s mother to the Ascot races provided the opportunity for a second chorus, it seemed unnecessary to insert a third chorus at the Embassy Ball. Although they did

not invent any characters, Lerner and Loewe did provide a variation of a Rodgers and Hammerstein–type subplot by expanding the role of Alfred P. Doolittle, Eliza’s father.

19

Despite these changes and other omissions and insertions that alter the tone and meaning of Shaw’s play, Lerner’s libretto follows much of the

Pygmalion

text with remarkable tenacity. In contrast to any of the adaptations considered here, Lerner and Loewe’s libretto leaves long stretches of dialogue virtually unchanged.

By November 1954 Lerner and Loewe had completed five songs for their new musical. Two of these, “The Ascot Gavotte” and “Just You Wait,” would eventually appear in the show. Another song intended for Eliza, “Say a Prayer for Me Tonight,” would be partially salvaged in the Embassy Ball music and recycled in the film

Gigi

(1958).

20

Also completed by November 1954 were two songs intended for Higgins, “Please Don’t Marry Me,” the “first attempt to dramatize Higgins’s misogyny,” and “Lady Liza,” the first of several attempts to find a song in which Higgins would encourage a demoralized Eliza to attend the Embassy Ball.

21

Rex Harrison, the Higgins of choice from the outset, vigorously rejected both of these songs, and they quickly vanished. The casting of Harrison, the actor most often credited with introducing a new kind of talk-sing, was of course a crucial decision that affected the musical characteristics of future Higgins songs.

22

A second try at “Please Don’t Marry Me” followed in 1955 and resulted in the now familiar “I’m an Ordinary Man.” “Come to the Ball” replaced “Lady Liza” and stayed in the show until opening night. Lerner summarizes the compositional progress of their developing show: “By mid-February [1955] we left London with the Shaw rights in one hand, commitments from Rex Harrison, Stanley Holloway, and Cecil Beaton [costumes] in the other, two less songs than we had arrived with [“Please Don’t Marry Me” and “Lady Liza”] and a year’s work ahead of us.”

23