Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber (25 page)

Read Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber Online

Authors: Geoffrey Block

The topical “Zip”—a song in which newspaper reporter Melba Snyder (played in the revival by Elaine Stritch) acts out her interview with Gypsy Rose Lee, “the star who worked for Minsky”—also underwent several lyrical changes in 1952. In the revival Melba opened the song with Hart’s earlier version of the first lines when she recalls her interviews with “Pablo Picasso and a countess named di Frasso.” It is possible that Picasso and di Frasso were more recognizable to an early 1950s audience than the revised 1940 lyric that paired Leslie Howard and Noël Coward. In the final chorus the then-better-known Arturo Toscanini replaced Leopold Stokowski as the leader of the “the greatest of bands,” and one stripper (Lili St. Cyr) replaced

another (Rosita Royce). Even present-day trivia buffs could not be expected to know who either stripper is (although it might be said that Lili St. Cyr has achieved immortality by being mentioned in “Zip”). The 1952 version of “Den of Iniquity” (act II, scene 2) replaced Tchaikovsky’s

1812 Overture

with Ravel’s

Boléro

and added a final lyrical exchange between Joey and Vera after their dance.

50

In his autobiography Abbott somewhat exaggeratingly refers to a preliminary script by librettist O’Hara as “a disorganized set of scenes without a good story line [that] required work before we would be ready for rehearsal.”

51

In fact, although it contains no lyrics among its indications for songs and displays several notable deletions and departures from his Broadway typescript in 1940 (including an ending in which Linda and Joey are reconciled), in most respects O’Hara’s preliminary typescript follows the story line of the 1940 version closely.

52

Some songs that became part of the Broadway draft, “That Terrific Rainbow,” “Happy Hunting Horn,” and even “Bewitched,” were not given any space at all in O’Hara’s preliminary script. Further, the early typescript offers no indication for a ballet, an idea that Abbott credits scene and lighting designer Jo Mielziner for suggesting during rehearsals.

53

The dialogue that precedes “The Flower Garden of My Heart” in the published libretto is also missing from the earlier draft, but in this case O’Hara’s description of this production number (original draft, beginning of act II) leaves no room for doubt that he was responsible for the idea of the ballet:

Song and StoryThe song is Richman corn [Harry Richman, who introduced Irving Berlin’s song “Puttin’ on the Ritz” in the 1930 film also called

Puttin on the Ritz

], the flower number kind of thing—every girl reminds me of a flower; here is a hydrangea, here is a crocus, etc. a

YOUNG MAN

stays in the spotlight, holding out a hand for Hydrangea, who is in silly nudish costume. He never quite lets her get all the way in the light, but hands her away with one hand as he reaches for Crocus with the other. He looks at the fannies etc. in a way to make them ridiculous, and is mugging terribly, even in rehearsal.

O’Hara’s typescript of the 1940 Broadway libretto (I-6–36) contains handwritten changes for “Bewitched,” the biggest song hit from

Pal Joey

. Here are the typed lyrics as they once appeared in the B and final A sections of the third A-A-B-A chorus.

|

|

|

|

The draft poses a cultural literacy problem for those who might not know, even in 1940, that Fanny Brice sang “My Man” in

Ziegfeld 9 O’Clock Frolic

(1920) and

Ziegfeld Follies

(1921), or that this song was originally the French song “Mon Homme” by Maurice Yvain and Channing Pollock.

54

Fortunately this lyric was abandoned. The first three lines were crossed out and replaced with the following handwritten script for the B section with the forced rhyme

pal

/ verti-

cal

:

When your dream boat is

leaking

And your pal ain’t your

pal

Geometrically

speaking

just keep it verti

cal

The final version published in 1940 with its paired rhymes in B, is not indicated in the O’Hara typescript:

|

|

|

|

All of these versions are variations on a theme that Hart explored in numerous songs, including “It’s Got to Be Love” discussed earlier: love as a sickness. Vera, the restless wife of the wealthy Prentiss Simpson, is generally in control of her emotions and entertains no delusions about the cause of her sleepless nights. In the verse that precedes the chorus she even refers to Joey as a “fool” and a “half-pint imitation,” but even this realization does not prevent her from catching the dreaded disease.

In his autobiography Rodgers recalls what he learned from his training in Goetschius’s class of five students: “Whenever Goetschius talked about

ending a phrase with a straight-out tonic chord (the first, third and fifth step of any scale), he would call it a ‘pig,’ his term for anything that was too easy or obvious. Once I heard the scorn in Goetschius’ voice I knew that I’d avoid that ‘pig’ as if my life depended on it.”

55

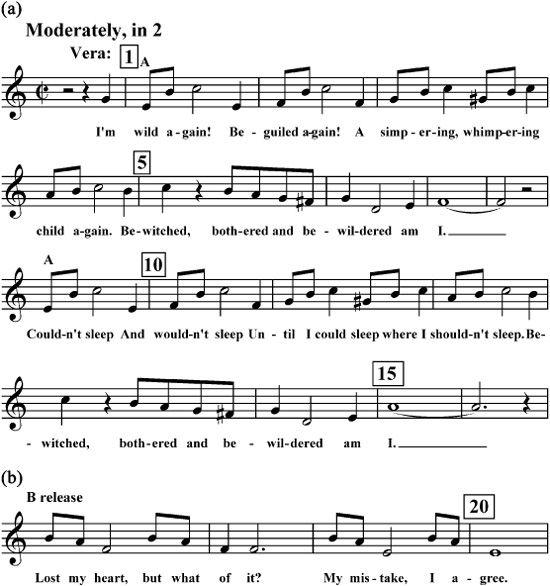

In “Bewitched” (

Example 5.6

) Rodgers avoids the infelicitously named “pig” at the end of the second eight-measure A section. He does this by moving to an A in measures 15 and 16 on the word “I” rather than the expected first note of the scale, F (also on the word “I”), that he set up at the end of the first A section in measures 7 and 8. The harmony, however, add interest as well as richness but not following the expectations of the melody. When the melody resolves to F (mm. 7–8), Rodgers harmonizes this note, not with F but with D minor (D-F-A, with F as the third rather than an F major triad, F-A-C, with F as the root); when the melody closes on A at the end of the second A section (mm. 15–16), the note that avoided the “pig,” Rodgers offers the F harmony expected eight measures earlier (but now a surprise), with A as the third. Only at the conclusion of the final A section (mm. 31–32) does Rodgers join melody and harmony (the note C in the melody matches the C major chord in the harmony) to conclude the song with a satisfying close.

Example 5.6.

“Bewitched” (chorus)

(a) Chorus, mm. 1-16.

(b) B section, or release, mm. 17-20

Rodgers also finds an effective musical means to capture Hart’s virtuosic depiction of Vera’s obsession. Hart conveys the society matron’s idée fixe by giving her thrice-repeated lyrics to conclude the first three lines of each A section, as in “I’m wild

again!

/ Beguiled

again!

/ A whimpering, simpering child

again

” (with the internal rhymes

wild, beguiled

, and

child

) before delivering the “hook” of the song’s title, “bewitched, bothered and bewildered” (always unrhymed) to conclude each A section. It is tempting to conclude that Rodgers’s musical characterization of Vera’s emotional state corresponds with uncanny accuracy to the lyrics. But since the lyrics apparently followed the music—in contrast to Rodgers’s subsequent modus operandi with Hammerstein—it is more accurate to admire Hart’s special sensitivity to Rodger’s music, which presents an equally repetitive musical line, the note B ascending up a half-step to C. By inverting the musical line (turning it upside down) in the B section (mm. 17–24), Rodgers manages to maintain Vera’s obsession while providing welcome musical contrast to the repetitive A sections.

Vera’s ability to rhyme internally also reflects her complexity and sophistication—or, as Sondheim would say, her education.

56

In other songs Hart’s lyrics convey literal lyrical parallels to Rodgers’s music. Examples of textual realism include Joey’s monotonous recitation of the alphabet and numbers to match the repeated notes in the verse of “I Could Write a Book,” the word “blue” in the phrase “but I’m blue for you” to match Rodgers’s “blue note” (a blue seventh) in the first period of “That Terrific Rainbow,” and the hunting imagery that corresponds to the horn-like fifths in “Happy Hunting Horn.” Other pictorial examples include the gunshot at the end of this last song to suggest fallen prey, the graphic chord each time Melba Snyder sings the word “Zip!,” and the dissonant chord cluster after she mentions “the great Stravinsky.”

Perhaps in an effort to musically integrate his

Pal Joey

songs, Rodgers maintains his obsession with the prominent half-steps that characterized “Bewitched.” No less than three other songs in

Pal Joey

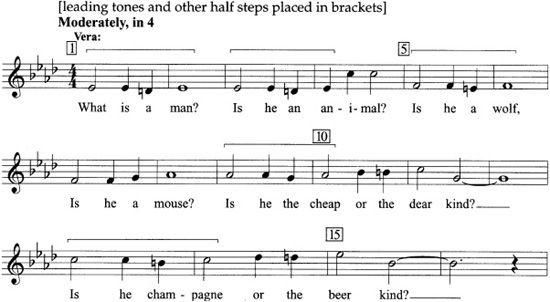

prominently employ various melodic permutations of the half-step interval. Can we attribute any dramatic meaning to this? By emphasizing this interval in both of Vera’s solo songs, “Bewitched” and “What Is a Man?” (

Examples 5.6

and

5.7

), Rodgers helps establish the musical identity of a woman who has allowed herself the luxury of an obsession. When Vera is with her paramour and sings with him, she has no need to obsess about him. Consequently, the half-step is absent in her duet with Joey, “Den of Iniquity.” Why Joey should sing half-steps so often in “Plant You Now, Dig You Later” is less explicable.

57

What remains consistent is that the songs prominently displaying the half-step are the “offstage” songs, not the songs sung in rehearsal or as part of the entertainment in Mike Spears’s nightclub or Chez Joey.

Example 5.7.

“What Is a Man?” (chorus, mm. 1-16)

The seemingly irresistible musical and psychological pull that characterizes the move from the seventh degree of a major scale (aptly labeled the leading tone) to the tonic, one half-step higher (e.g., B-C in the key of C), was also used to produce meaningful dramatic effects in other shows. In

South Pacific

(1949) Rodgers (with Hammerstein) greases rather than avoids the “pig” (an F) for the sake of verisimilitude in “I’m Gonna Wash That Man Right Outa My Hair.” In this well-known song Rodgers conveys Nellie Forbush’s delusion by introducing the oft-repeated title line with an equally repetitive ascending scalar phrase (C-D-E-F) that relentlessly and obsessively returns to the central key and thereby exposes her failure to accomplish her task. Later in the show when she admits to herself and her fellow nurses that she is, in fact, “in love with a wonderful guy,” Nellie sings an exaggerated eighteen repetitions of the half-step interval (again from the leading tone up to the tonic) on the repeated words “love, I’m in” (B-C-C, B-C-C, etc.). In “Bali Ha’i,” also from

South Pacific

, Rodgers convincingly conveys the mysterious

quality and seductive call of the exotic island by its emphasis on repeated half-steps (e.g., “Ha’i may call you” becomes F -F

-F -F

-F -G).

-G).