Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber (42 page)

Read Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber Online

Authors: Geoffrey Block

The idea for setting Molnár’s play came from the Theatre Guild, who naturally wanted to reproduce a second

Oklahoma!

Writing in the

New York Times

four days before the birth of the new sibling, Hammerstein recalled Helburn and Langner propositioning the creators of their previous blockbuster in Sardi’s “toward the end of January, 1944.” The main obstacle for Hammerstein was the Hungarian setting. When, the following week, the persistent Helburn offered a more promising alternative locale in Louisiana, the required dialect also proved to be “a disconcerting difficulty” for the librettist. Sources agree that the workable idea to “transplant the play to the New England coast” came from Rodgers and that the starting point for the show was Billy Bigelow’s “Soliloquy.” In

Musical Stages

Rodgers wrote that once the team had conceived “the notion for a soliloquy in which, at the end of the first

act, the leading character would reveal his varied emotions about impending fatherhood,” the central problem of how to sing

Liliom

was resolved.

2

Although their contract allowed Rodgers and Hammerstein considerable latitude in their adaptation, they were nonetheless relieved to learn during an early rehearsal run-through that the playwright had given his blessing to their changes, including a greatly altered ending.

3

In the play, a defiant Liliom does not regret his actions and is doomed to purgatory for fifteen years. He is then required to return to earth for a day to atone for his sins. While on earth, disguised as a beggar, Liliom slaps his daughter when she refuses the star he stole from heaven; she sends him away, and the play ends on this pessimistic note. In the musical a much more sympathetic Liliom, renamed Billy Bigelow, comes to earth by choice, appears as himself, and can choose either to be seen or to remain invisible. As in the play he has stolen a star and slaps his daughter Louise, but now the slap feels like a kiss (in the play it felt like a caress). In stark contrast to the play, the musical’s final scene shows Billy, in his remaining moments on earth, helping his “little girl” at her graduation to overcome her loneliness and misery. To the inspirational strains of “You’ll Never Walk Alone,” with its somewhat dubious advice if taken literally (“when you walk through a storm keep your chin up high”), Louise finds the courage to live, Julie realizes that her marriage—in Molnár’s less family-oriented play she remained Billy’s mistress—was worth the pain. Billy redeems his soul, and even the most jaded of contemporary audiences find themselves shedding real tears.

Auditions began in February 1945 and tryouts took place the following months in New Haven (March 22–25) and Boston (March 27–April 15). Elliot Norton describes the principal dramatic alteration made during the Boston tryouts:

The original heaven of

Carousel

was a New England parlor, bare and plain. In it sat a stern Yankee, listed on the program as He. At a harmonium, playing softly, sat his quiet consort, identified as She. Later some observers [including Rodgers] referred to this celestial couple as Mr. and Mrs. God….

Richard Rodgers, walking back to the hotel with his collaborator afterwards, put it to Oscar Hammerstein bluntly:

“We’ve got to get God out of that parlor!”

Mild Oscar Hammerstein agreed.

“I know you’re right,” he said. “But where shall I put Him?”

“I don’t care where you put Him,” said Richard Rodgers. “Put Him up on a ladder, for all I care, only get Him out of that parlor!”

So Oscar Hammerstein put Him up on a ladder. He discarded the sitting room too, and put his deity into a brand new sequence.

On a ladder in the backyard of heaven, He became the Star-Keeper, polishing stars which hung on lines strung across the floor of infinity, while a sullen Billy Bigelow looked and listened to his quiet admonitions.

4

Carousel

’s premiere took place at the Majestic Theatre on April 19, and the show closed a little more than two years later on May 24, 1947, after a run of 890 performances. Following a successful national tour,

Carousel

began another impressive run of 566 performances at London’s Drury Lane on June 7, 1950 (closing on October 13, 1951). Major New York revivals took place at the New York City Center Light Opera in 1954, 1957, and 1967; at the Music Theater of Lincoln Center in 1965; and in 1994 with an acclaimed New York staging based on the Royal National Theater of Great Britain production.

Almost without exception

Carousel

opened to rave reviews. Nevertheless, most critics could not resist the temptation to compare the new work to

Oklahoma!

, then beginning its third year on Broadway. Although an anonymous reviewer in the

New York World-Telegram

found “the distinct flavor of ‘Oklahoma!’” in “A Real Nice Clambake,” persistent rumors that the latter song once belonged to the former and titled “A Real Nice Hayride,” are unsubstantiated.

5

Ward Morehouse’s review in the

New York Sun

is representative in its conclusion that the laudatory

Carousel

could not quite match the earlier masterpiece: “‘Carousel,’ a touching and affecting musical play, is something rare in the theater. It’s a hit, and of that there can be no doubt. If it is not the musical piece to challenge ‘Oklahoma’ for all-time honors it is certainly one that deserves its place in the 44th Street block. The team of Rodgers and Hammerstein will go on forever.”

6

A handful of reviewers regarded the new musical more favorably than its predecessor. According to John Chapman, “‘Carousel’ is one of the finest musical plays I have seen and I shall remember it always. It has everything the professional theatre can give it—and something besides: heart, integrity, an inner glow.”

7

Although reviewers then and now found the second-act ballet too long, Robert Garland wrote that “when somebody writes a better musical play than ‘Carousel,’ written by Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein, Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein will have to write it.”

8

By the time it returned to New York in 1954 the climate of critical opinion had shifted further, and Brooks Atkinson could now write that

Carousel

“is the most glorious of the Rodgers and Hammerstein works.” Atkinson continued: “Three of the Rodgers and Hammerstein shows have had longer runs than ‘Carousel.’ It is the stepchild among ‘Oklahoma!’ ‘South Pacific,’ and ‘The King and I.’ But when the highest judge of all hands down the ultimate verdict, it is this column’s opinion that ‘Carousel’ will turn out to

be the finest of their creations. If it were not so enjoyable, it would probably turn out to be opera.”

9

Carousel

would also remain the pride and joy of its creators. For Rodgers, especially, the second musical with Hammerstein stood as his personal favorite among all his forty musicals. Without any false sense of modesty he conveyed his reasons: “Oscar never wrote more meaningful or more moving lyrics, and to me, my score is more satisfying than any I’ve ever written. But it’s not just the songs; it’s the whole play. Beautifully written, tender without being mawkish, it affects me deeply every time I see it performed.”

10

The above critical reception and the judgment of its authors partially explains why

Carousel

and not

Oklahoma!

was selected for examination in the present survey. But given the importance attributed to

Oklahoma!

as the “Eroica” Symphony of the American musical, the question “Why not

Oklahoma!

?” nevertheless lingers and needs to be addressed. The simple answer is that

Oklahoma!

’s incalculable historical importance as the musical that changed all musicals is equaled and arguably surpassed dramatically and musically by

Carousel

. Not content to merely duplicate their earlier success, Rodgers and Hammerstein in their second musical attempted to convey a still richer dramatic situation with characters who were perhaps more complexly realized, through music, than the inhabitants of the Oklahoma Territory.

Further, the artistic ambitions in

Carousel

are matched by a deeper relationship between music and drama. The integrated songs in

Oklahoma!

grow naturally from the action and reflect each character’s idiosyncratic nature. But, like

Show Boat

and

Porgy and Bess

before it and

West Side Story

after, the music of

Carousel

develops action and explores nuances of characterization that frequently transcend what the characters themselves understand.

11

The analysis that follows will suggest how Rodgers and Hammerstein’s imitation may have surpassed (artistically if not in popularity) not only its model but many other musicals that have had their two or more hours’ traffic on the Broadway stage.

In several respects Julie Jordan, who moves us by her ability to see the good qualities in her abusive husband, Billy Bigelow, and by her uncompromising loyalty to his memory, bears a stronger kinship to Hammerstein’s

Show Boat

heroine Magnolia Ravenal than to

Oklahoma!

’s Laurey. Even the message of its central song, “What’s the Use of Wondrin,’” like that of

Carousel

as a whole, echoes Hammerstein’s theme in

Show Boat

as embodied in the song “Can’t Help Lovin’ Dat Man”: once fate brings two lovers together “all the rest is

talk.” Julie shares with Magnolia rather than her Oklahoma cousin a common destiny—to love a man who will eventually generate much unhappiness. Like Magnolia, Julie will also meet the man she will love early in her show.

12

Also like Magnolia and Ravenal, Julie and Billy—as well as Laurey and Curley in the analogous “People Will Say We’re in Love”—describe a hypothetical rather than an acknowledged love, at least at the outset of their duets. The romantic leads in

Show Boat

, however, declare their love in the waltz “You Are Love” at the emotional climax of act I and offer additional explanations for their feelings early in act II when they sing “Why Do I Love You?” (at least before Hal Prince gave this song to Parthy in the 1994 Broadway revival). In contrast, Julie and Billy, more tragically, are unable to express their love directly, not only in their first duet, “If I Loved You,” but at any point in the drama, at least while Billy is alive.

In an extremely poignant moment that immediately follows Billy’s suicide in act II, scene 2, Julie finally manages to share her feelings with her deceased husband: “One thing I never told you—skeered you’d laugh at me. I’ll tell you now—(

Even now she has to make an effort to overcome her shyness in saying it

) I love you. I love you. (

In a whisper

) I love—you. (

Smiles

) I was always ashamed to say it out loud. But now I said it. Didn’t I?”

13

Outside Julie’s cottage three scenes later, Billy, whose presence is felt rather than seen or heard, finally sings his love in the following reprise (release and final A section) of “If I Loved You.” According to Rodgers, this inspired new idea was, after the removal of Mr. and Mrs. God, the only other major change made during the tryouts. “Longing to tell you, / But afraid and

shy

, / I let my golden chances pass me

by

. / Now I’ve lost you; / Soon I will go in the mist of day, / And you never will know / How I loved you. / How I loved you.”

14

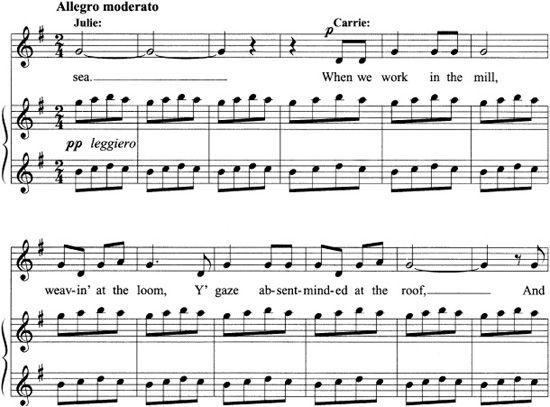

Just as Kern conveys Magnolia’s penetration into Ravenal’s being by merging her music with his, Rodgers finds subtle musical ways to let audiences know that Julie’s love for Billy is similarly more than hypothetical. During the opening exchange between Carrie and Julie, for example, Julie’s friend makes it clear that she knows why Julie is behaving so “queerly.” First, Carrie describes Julie’s recent habit of rising early and sitting silently by the window. Julie lamely denies this circumstantial evidence of love sickness (“I like to watch the river meet the sea”), but Carrie’s next and more telling observation of Julie’s behavior on the job, the “Mill Theme” (

Example 9.1

) is incontrovertible: “When we work in the mill, weavin’ at the loom, / Y’ gaze absent-minded at the

roof

, / And half the time yer shuttle gets twisted in the threads / Till y’can’t tell the warp from the

woof

!”

15

Although Julie denies even this evidence with a “‘Tain’t so!,” her strangeness, even more than Frankie’s in

On Your Toes

, cannot be attributed to tonsillitis or to the combination of pickles and pie à la mode: it’s got to be love. The sensitive Carrie, now that Julie has a “feller,” can inform Julie of her own romantic good fortune in being courted by the young entrepreneur Enoch Snow. This time Julie does not attempt to deny Carrie’s presumption. When Julie explains to Billy minutes later how she would behave, hypothetically, “if she loved him,” Rodgers and Hammerstein have her describe, again to the “Mill Theme,” the behavior that Carrie has in fact already observed. Julie’s denial of love may satisfy Billy, but it fails to convince either Carrie or a knowing audience who has more than sufficient textual and musical evidence to catch Julie in her self-deception.