Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber (41 page)

Read Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber Online

Authors: Geoffrey Block

Although the story is roughly equivalent to the stage version, several of the plot machinations are quite different. Rodney (renamed Eddie) Hatch has been given a new male friend Joe Grant, played by one of the two actors whose actual voices are heard on the soundtrack, Dick Haymes, a popular singer of the day who played a major character in Rodgers and Hammerstein’s

State Fair

three years earlier.

44

Considering how little they sing together, Rodney spends a considerable amount of time onscreen with Venus (Ava Gardner). Onstage, Gloria (Olga San Juan, the other singer in the film) disappears for long stretches; now she shares music of the film with Joe, and, not surprisingly, they gradually fall in love. As in the stage version, Rodney will end up with a Venus look-alike, this one by the name of Venus Jones (also played by Gardner just as Mary Martin played Venus and her earthling surrogate onstage) after the real Venus has returned to the land of the Gods and her earthly remains have become re-solidified as a statue. The popular Haymes naturally sings in two of the three songs, the second of which, formerly a solo for Venus (Martin), is now a double duet in two juxtaposed scenes, one between Eddie and Venus, the other between Joe and Gloria, an interesting cinematic flourish. The other major new plot wrinkle revolves around Whitfield (onstage Whitelaw) Savory’s gradual awareness

that the love of his life is not Venus but his assistant Molly, played with characteristic acerbic wit by Eve Arden.

The role of Hatch was assigned to the non-singing Robert Walker. In recent years Walker had acted the role of two great songwriters, Jerome Kern in

Till the Clouds Roll By

(1946) and Johannes Brahms in

Song of Love

(1947) and was convincing as the milquetoast window dresser who brings the statue of Venus to life with an impulsive kiss. Gardner’s voice was dubbed by Eileen Wilson; three years later in the 1951 remake of

Show Boat

, Gardner’s Julie LaVerne would be dubbed by Annette Warren on screen (although strangely Gardner’s own voice is heard on the

Show Boat

soundtrack album). Not long after making her first major film impression playing opposite Burt Lancaster in

The Killers

(1946), based on a Hemingway story, Gardner was invariably assigned to roles where physical beauty was a major prerequisite. Ephraim Katz in

The Film Encyclopedia

offers the following description that might help explain why Gardner was chosen to play Venus: “A sensuous, sloe-eyed beauty, with a magnetic, tigresslike quality of sexuality, she replaced Rita Hayworth in the late 40s as Hollywood’s

love goddess

[italics mine] and occupied that position until the ascent of Marilyn Monroe in the mid-50s.”

45

Although it remains not only a poor replica of the

Venus

book, lyrics, and score seen and heard onstage four years earlier, the musical film

Venus

is not without its charms as a story. Walker, Arden, and Tim Conway as Whitfield carry off their respective characters with aplomb, Haymes sings his two songs mellifluously, and the visual fluctuations between Venus/Eddie and Gloria/ Joe in “Foolish Heart” are welcome. The film also contains some chase scenes that recall the early Keystone Cops routines, which may be attributed to the fact that the film’s director William Seiter was himself once a Keystone Cop.

After experiencing the indignity of having songs deleted and, even worse, replaced, in

Lady in the Dark

, composer Kurt Weill insisted on a contract for

One Touch of Venus

that would include a “non-interpolation clause,” in which no music by other composers could be inserted. As he explained in a letter to his agent, Leah Salisbury, “All the songs in the picture have to be taken from the score, and the underscoring has to be based on themes from the original score.”

46

The studio honored these conditions to the letter; the end result was a film adaptation that contained only the shell of the original score (and no new songs by others to fill in) and a few Weill songs inserted here and there between long stretches of dialogue.

This survey of film adaptations from

Show Boat

to

One Touch of Venus

reveals much about Hollywood’s response to their Broadway sources. The goal during these years was to entertain and engage a film audience, not to offer a replica

of a sacrosanct stage artifact. Only the Nunn version of

Porgy and Bess

, which appeared nearly sixty years later, comes close to depicting a Broadway stage version, but even here the very completeness of the film, ironically, belies its “authenticity” (a problematic term) since in 1935 attendees at the opera’s first performances saw and heard a version of the work perhaps forty minutes shorter. Most of the films discussed in this chapter present heavily revised books and brutally abbreviated scores, sometimes with additional music by the original or newly contracted composers, and sometimes with recycled music from the original songwriter’s trunk placed in new contexts. It is probably not an exaggeration to assert that with the exception of

Show Boat

, these adaptations fall short of the best original films that use the music of the composers and lyricists featured in act I of

Enchanted Evenings

. We will conclude this chapter with a summary of other adaptations in relation to the original musicals with scores by Kern, Porter, the Gershwins, and Rodgers and Hart.

47

• KERN

Of this quartet, Kern was probably the most frequently adapted with reasonable success. In fact, a number of films retained a significant amount of his music, including

The Cat and the Fiddle

and

Music in the Air

in 1934 and

Sweet Adeline

and

Roberta

in 1935.

• PORTER

We have already noted that the adaptation of

Gay Divorce

(renamed

The Gay Divorcée

) salvaged only one song, “Night and Day.” Film adaptations of

Something for the Boys

and

Mexican Hayride

contained no songs by Porter;

Paris

and

Fifty Million Frenchmen

confined Porter’s music to background noise;

Let’s Face It

offered two songs;

Dubarry Was a Lady

, three; and

Panama Hattie

, four. For worthy films with Porter’s music—prior to the 1953 adaptation of

Kiss Me, Kate

discussed in

chapter 14

—one would have to turn to the original film musicals

Born to Dance

(1936),

Rosalie

(1937), and

Broadway Melody of 1940

, and the modern-day biopic

De-Lovely

(2004), the latter chock full of stylistically updated Porter chestnuts starring Kevin Kline as the composer-lyricist.

• THE GERSHWINS

The films of George and Ira Gershwin were similarly disappointing as Broadway adaptations.

Strike Up the Band

offers only the title tune. At least the 1943

Girl Crazy

, also starring Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney, had the sense to retain six of the 1930 original’s fourteen songs, plus the Gershwin hit originally composed in 1924 for Fred Astaire in

Lady, Be Good!

, “Fascinating Rhythm.”

Funny Face

(1957), with Astaire reprising his original stage role thirty years later, satisfies as a film musical, but with only five songs

from the original, “Clap Yo’ Hands” from another show, three interpolated song numbers by Roger Edens and Leonard Gershe, and a new scenario and script, it falls far short as a reliable adaptation of the Gershwin musical as it appeared onstage. Fortunately, George lived long enough to complete outstanding film scores the year he died (1937) for

Shall We Dance

with Astaire and Rogers and

Damsel in Distress

with Astaire, George Burns and Gracie Allen, and the non-dancing Joan Fontaine. Long after George’s death his music and Ira’s lyrics served as the centerpiece for another fine original musical,

An American in Paris

(1951), produced by Arthur Freed, directed by Vincente Minnelli, to an award-winning screenplay by Alan Jay Lerner, and starring its choreographer Gene Kelly.

• RODGERS AND HART

Of the many films adapted from the stage musicals of Rodgers and Hart, none rivaled the increasingly recognized classic original film

Love Me Tonight

(1932), produced and directed by Rouben Mamoulian and starring Maurice Chevalier, Jeanette MacDonald, and Charles Ruggles. Of the rest,

Too Many Girls

, directed by its Broadway director George Abbott and starring four members of the original stage cast, managed to salvage half of the score, seven songs—if you have been counting, this is close to a record for film adaptations.

Girls

also added a new instant classic by Rodgers and Hart, “You’re Nearer,” and even kept much of the original libretto intact. Five of the six songs from Rodgers and Hart’s

Jumbo

can be heard in the 1962 film, which retains the basic plot and, twenty-seven years after its Broadway debut, its original star, Jimmy Durante.

In the film adaptation of

On Your Toes

(Warner Bros. 1938) none of the songs are sung, and only four tunes are heard in unobtrusive underscoring (“There’s a Small Hotel,” “Quiet Night,” and “On Your Toes”). On the other hand,

Toes

does contain the “Princesse Zenobia” and “Slaughter on Tenth Avenue” ballets with the original choreography by George Balanchine and featuring Vera Zorina. About thirty seconds of the latter can be seen in the documentary

Richard Rodgers: The Sweetest Sounds

, but the film itself was never released on either VHS or DVD.

48

The best place to find “Slaughter” on film is the athletic duet between Rodgers and Hart stage alums Gene Kelly (the original Pal Joey) and Vera Ellen (Mistress Evelyn in the 1943 revival of

Connecticut Yankee

) on the easily obtainable Rodgers and Hart biopic

Words and Music

(1948).

49

Although three of the films discussed in this chapter are difficult to locate and all offer distortions of one kind or another, these film adaptations offer their share of compensations. In particular,

Show Boat

and

Anything Goes

let us see

some of the original stars or other actors and actresses associated with early productions. Seeing and hearing Charles Winninger, the original Broadway Cap’n Andy, Paul Robeson, the original London Joe, or Ethel Merman, the original Reno Sweeney sing their songs in a film that is roughly contemporaneous to their theatrical performances is worth the time it takes to find these films. Some of the shows have even retained a surprising amount of original dialogue, even when the plots are greatly altered. Although they are destined to disappoint musically they are worth getting to know, as long as you know what you’re missing.

CT

II •

T

HE

B

ROADWAY

M

USICAL

A

FTER

O

KLAHOMA

!

CAROUSEL

The Invasion of the Integrated Musical

W

orking under the premise that success begets success, Rodgers and Hammerstein followed the phenomenal triumph of

Oklahoma!

(1943) by assembling much of the same production team for their second hit,

Carousel

(1945). Like their historic opening salvo,

Carousel

was produced by the Theatre Guild and supervised by Theresa Helburn and Lawrence Langner, the pair who had given Rodgers and Hart their big break in 1925,

The Garrick Gaieties

. For their director the Theatre Guild selected Rouben Mamoulian, who had directed

Oklahoma!

as well as Rodgers and Hart’s classic film

Love Me Tonight

in 1932, the play

Porgy

in 1927, and the opera

Porgy and Bess

in 1935 (both of the latter were also Theatre Guild productions). Agnes de Mille was again asked to choreograph, and Miles White designed the costumes.

Ferenc Molnár’s play

Liliom

, which premiered in Hungary in 1909, had been successfully presented by the Guild in 1921 with the legendary Eva Le Gallienne and Joseph Schildkraut, and more recently in 1940 in a production that starred Ingrid Bergman and Burgess Meredith. After some initial resistance, Molnár, who had allegedly turned down an offer by Puccini (and Weill and perhaps Gershwin as well) to make an opera out of his play, reportedly agreed in 1944 to allow the Theatre Guild to adapt his play: “After fifteen months, all the legal technicalities involved in the production of the musical version of

Liliom

were settled last week.”

1

The

New York Post

went on to say that “the smallest percentage, eight tenths of one percent, go to Ferenc Molnár, who merely wrote the play.”

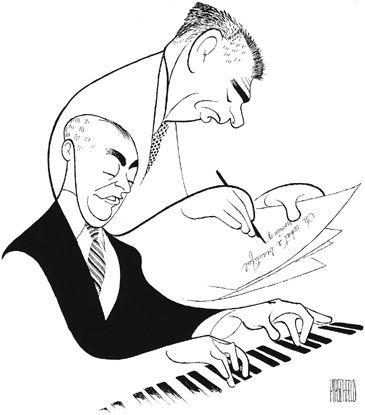

Rodgers and Hammerstein. © AL HIRSCHFELD. Reproduced by arrangement with Hirschfeld’s exclusive representative, the MARGO FEIDEN GALLERIES LTD., NEW YORK.

WWW.ALHIRSCHFELD.COM