Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber (19 page)

Read Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber Online

Authors: Geoffrey Block

But Gershwin went beyond Kern in discovering varied and ingenious new ways to transform his melodies (even his hit tunes) for credible dramatic purposes. In altering Cap’n Andy’s theme and Magnolia’s piano theme, Kern altered tempo and character—and presumably asked Robert Russell Bennett to orchestrate these transformations—but he did not change the pitch content of either theme. When Gershwin musically responds to the ever-changing dramatic circumstances of his characters and their relationships, he frequently alters the pitches of the initial melodies by using a technique known as paraphrase. As his characters evolve, Gershwin adds and subtracts pitches and alters rhythms to create new melodies. In most cases these new melodies retain the identity inherent in their fundamental melodic contours. Some of Gershwin’s melodic transformations are difficult to perceive and are consequently meaningless to most listeners. Other transformations are questionably related to the central themes. The remarks that follow will focus on the most audible and dramatically meaningful of Gershwin’s melodic manipulations, a union of craft and art.

Musicals, operatic and otherwise, thrive when they show two people in love that audiences can care about. The opera

Porgy and Bess

, like all the adaptations treated in this book, similarly places its greatest dramatic emphasis on the love-story component of its literary source. A related theme is the attempt of the principal characters to overcome their physical and emotional handicaps and dependencies, their loneliness and poor self-esteem, and to establish themselves as fully accepted members within a loving community. Act II, scenes 1 and 3, provide a good introduction to how Gershwin created a symbolic musical language to express these great dramatic themes.

At the musical heart of the opera stands (or kneels, depending on the production) Porgy, not only because Gershwin gives him several themes but because these themes relate so closely to the Catfish Row community.

74

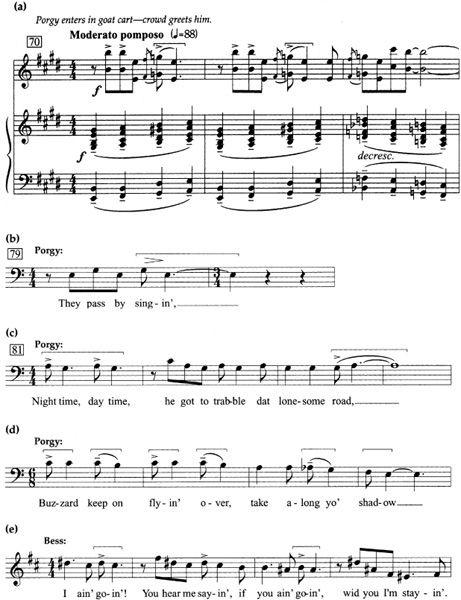

Porgy may not feel as though he is a “complete” man (until ironically he gains his manhood and loses his humanity by killing Crown and then gloating over it), but from the outset of the drama he is definitely, unlike Bess, part of the community. It is fitting, then, that his main theme, shown in

Example 4.1a

, introduced by the orchestra rather than by Porgy himself, emphasizes a pure (or perfect) fifth and a minor (or blue) third, intervals that reasonably (if somewhat inexplicably) represent both the solidity and folk-like nature Porgy shares with Catfish Row as well as his sadness before he met Bess.

75

Soon after his introduction in act I Porgy sings the first of two loneliness themes, “They pass by singin’” (

Example 4.1b

), a theme that melodically consists entirely of minor thirds and a theme that will retain its strong rhythmic profile in many future contexts.

76

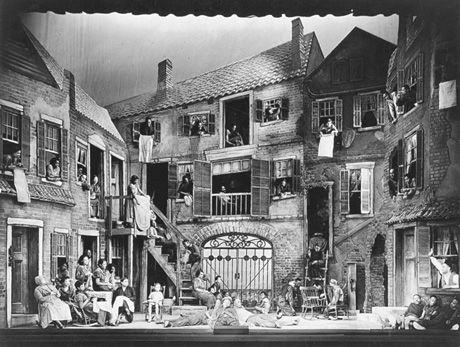

Porgy and Bess

, act II, scene 1. Todd Duncan in window at right (1935). Museum of the City of New York. Theater Collection.

Moments later in this same monologue Gershwin has Porgy introduce a second loneliness theme (

Example 4.1c

), a melody that emphasizes a major second on “night time, day time” and “lonesome road” and a prominent syncopated rhythm ( ) derived from the last two notes of Porgy’s central theme (

) derived from the last two notes of Porgy’s central theme (

Example 4.1a

) and the rhythm of “singin’” (

Example 4.1b

).

77

Having introduced these three rhythmically connected Porgy themes in the opening scene, Gershwin will, in act II, scene 1, establish connections between Porgy and his community to reveal how Bess and Catfish Row work together to eliminate Porgy’s loneliness.

Example 4.1.

Porgy’s themes

(a) Porgy’s central theme

(b) Loneliness theme

(c) Loneliness theme

(d) Loneliness theme in “Buzzard Song”

(e) Loneliness theme in “Bess, You Is My Woman Now”

Porgy’s loneliness themes will undergo further audible transformations in the “Buzzard Song.” Throughout much of the “Buzzard Song” Gershwin emphasizes the minor thirds that were so prominent in Porgy’s central theme (e.g., “Don’ you let dat buzzard keep you hangin’ ‘round my do’”), and he also retains the syncopations of the loneliness theme. But as seen in

Example 4.1d

, Gershwin intensifies Porgy’s loneliness by contracting his major second a half step in the song’s principal melodic motive to create a still-harsher minor second. Even if one questions the dramatic effect of the “Buzzard Song” on this scene and the drama as a whole and embraces the decision to remove it, its omnipresent syncopations and dissonant minor seconds certainly provide a fitting musical counterpart to Porgy’s sudden apprehension upon seeing a buzzard.

The original form of Porgy’s loneliness theme returns in act II, scene 1, to introduce the duet between Porgy and Bess, “Bess, You Is My Woman Now.” The dramatic point of this duet, that Bess’s love can eliminate Porgy’s loneliness, soon becomes apparent when we hear Bess sing the second loneliness theme, “I ain’ goin’! / You hear me

sayin

,’ / if you ain’ goin,’ / wid you I’m

stayin

’” (

Example 4.1e

). Significantly, Porgy does not sing about his loneliness with Bess, and when Bess returns to it later in the song, Porgy sings a different counter line. In their fleeting, almost magical, moment of happiness, Bess has thus absorbed Porgy’s loneliness while at the same time relieving her own. Act II, scene 1, is thus the only scene in which Porgy and Bess express their love with uninhibited optimism for their future together. Musically, “Bess, You Is My Woman Now,” as Starr has noted, marks a special and ephemeral moment of F-sharp major, a distant key heard nowhere else in the opera.

78

The final transformation of Porgy’s loneliness in act II, scene 1, occurs in the pseudo-spiritual “Oh, I Can’t Sit Down!” that immediately follows Porgy and Bess’s love duet, a spiritual that could, without stretching things too much, be interpreted as a melodic transformation of “It Take a Long Pull to Get There” (with a switch of mode from minor to major) and especially “I Got Plenty o’ Nuttin.’” In any event, all of these melodies display the short-long syncopated loneliness rhythm (in most cases the short note receives an accent) prominently at the ends of many phrases.

79

In the main portion of this final chorus Gershwin not only preserves the G major tonality of Porgy’s earlier tune, he creates another melody that manages to sound new while operating completely within Porgy’s perfect fifth. More strikingly, Gershwin in “Oh, I Can’t Sit Down” maintains the melodic connection with Porgy’s central theme (the prominent minor thirds in the opening musical line that correspond to the song title) and the rhythmic connection (the characteristic syncopation on “happy

feelin

,’” “no con

cealin

,’” and many other words) with Porgy’s loneliness theme.

Through such devices Gershwin conveys the message that the most effective way to overcome loneliness is to acknowledge it musically, then

transform its character, also musically. Not only has Bess’s love for Porgy at least momentarily conquered Porgy’s loneliness, Catfish Row revels in this transformation. Ironically, at the end of this scene Bess does in fact leave Porgy, albeit at his urging, to join the community at their picnic, an act that sets up her eventual fall from grace. Nevertheless, the people of Catfish Row invite Bess to join them on Kittiwah Island, a strong sign of her successful integration into the community.

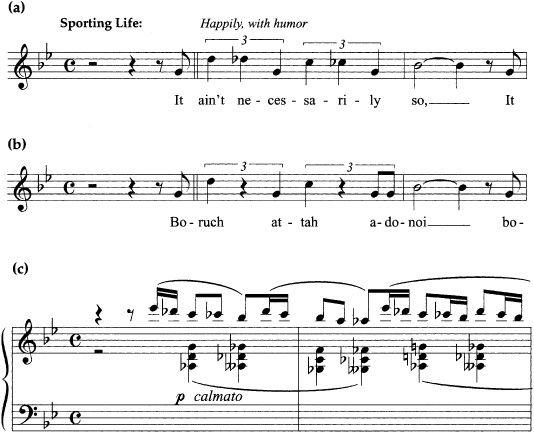

If Porgy’s themes and their transformations in community songs serve to emphasize the unity between Porgy and Catfish Row, Sporting Life’s central theme—both at his entrance in act II, scene 1, and in the main melody of “It Ain’t Necessarily So” in act II, scene 2—demonstrates his separation and estrangement from this same community (

Example 4.2

). Just as Cap’n Andy’s shrewish wife Parthy possesses a melody that cannot live in harmony with the other themes that dwell within the secure perfect fourths of the Mississippi River (

Example 2.3

, p. 31), Sporting Life’s attempt to be a part of Catfish Row is demonstrably false, musically as well as dramatically.

Example 4.2.

Sporting Life’s themes

(a) Sporting Life

(b) Jewish prayer (“Boruch attah adonoi”)

(c) Happy Dust theme

Like Porgy’s theme, the melody that Gershwin assigned to Sporting Life is encompassed within a perfect fifth and concludes with a prominent minor (or blue) third. What betrays Sporting Life as an unwelcome outsider, however, is the prominence of the diminished fifth (the same sound as Parthy’s dissonant augmented fourth, or tritone), an interval that has been associated with the devil since the Middle Ages when it was known as the

diabolus in musica

. The chromatic machinations of Sporting Life’s theme appropriately enough suggest the movements of a snake-in-the-grass, analogous to the serpent who manages to tempt Eve out of the Garden of Eden. The agent of Sporting Life’s evil, his “happy dust” (cocaine), receives a suitably chromatic, serpentine theme (

Example 4.2c

).

80

Even if one takes the optimistic view that Porgy will eventually find Bess after the final curtain, it must be acknowledged that both Bess and Porgy have been forced to leave Eden and search elsewhere for the Promised Land.

The third principal male character, Crown, exhibits a highly charged orchestral theme that contrasts markedly with Porgy’s theme (

Example 4.3

).