Eat and Run: My Unlikely Journey to Ultramarathon Greatness (26 page)

Read Eat and Run: My Unlikely Journey to Ultramarathon Greatness Online

Authors: Scott Jurek,Steve Friedman

Tags: #Diets, #Running & Jogging, #Health & Fitness, #Sports & Recreation

John and four buddies from the RAF decided to make the attempt. In the words of the Irishman John McCarthy, “We established a credible and historically correct route using ancient military roads, pilgrim ways, dry river beds and goat tracks, taking into consideration the ancient political alignments and enemy states to be skirted.” The five runners set off from Athens on October 8, 1982, and the “three Johns” succeeded, arriving in Sparta in front of the statue of Leonidas on October 9: John Scholten in 35.5 hours, John Foden in 36 hours, and John McCarthy in just under 40 hours.

They decided to establish a yearly run that, in the Olympic vein, would offer no prize money or commercial gain but would instead promote a spirit of international cooperation and fellowship. Indeed, the Spartathlon is one of the best values in the world of ultrarunning. The entry fee of $525 gets you lodging and meals for six days as well as two of the best awards ceremonies you’ll ever attend, museum tours, bus transportation, and ample food and water at the aid stations.

In 1983, 45 runners from 11 countries competed. In 1984, the International Spartathlon Association was founded to manage the race.

After he retired, Foden stayed active in the ultra community, promoting races all over the world. I found his booklet, “Preparing for & Competing in Your First Spartathlon,” very helpful my first year. He continued to break age group records into his seventies, and in 2005 he was the oldest participant in the 300-km Haervejsvandring Walk from Schleswig in Germany to Viborg in North Denmark in seven days.

In the Western States and other ultras, I had battled the best long-distance runners the United States had to offer. The Spartathlon attracted the finest in the world. When I showed up in 2007, I faced the 2001 champion, Valmir Nunes from Brazil. He had just broken my Badwater course record and held the third fastest 100-km time in the world. There was an impressive number of other former champions: the 2000 champion, Otaki Masayuki, and the 2002 (and eventual 2009) champion, Sekiya Ryoichi, from Japan. Markus Thalmann, the 2003 champion from Austria, was there, too, as well as Jens Lukas from Germany, who had won in 2004 and 2005. When I had won the previous year, I was the first North American to do so. The greatest Spartathlon champion was—and probably always will be—homegrown. Twenty-six-year-old Yiannis Kouros was living a Spartan lifestyle as a groundskeeper near Tripoli when the Johns undertook the first Spartathlon test run in 1982. Hearing of their mission to resurrect Pheidippides, the literary-minded Kouros was entranced. He had run twenty-five marathons at that point, with some modest successes and a personal record of 2:25; he was about to find his niche. In 1983, Kouros burst onto the ultramarathon scene with a Spartathlon and ultramarathon debut in an astounding 21:53. His margin of victory was so great—more than 3 hours ahead of the runner-up—that the race director refused to award him the trophy for two days—until it could be proven that he had not cheated.

He went on to win the Spartathlon three more times, and these remain the four fastest times ever for the course, ranging from 20:25 to 21:57. Pheidippides couldn’t have done better. I’ve chased many a record, but my best times are in fifth, sixth, and seventh place overall, 23 minutes behind his slowest time.

Now semi-retired from ultras, Kouros is undefeated in any continuous world-class road ultramarathon competition beyond 100 miles, and he still holds world records on the road and track for almost all distances and durations beyond the 12-hour event.

Kouros is a philosopher-athlete in the ancient Greek tradition. His results seem to stem from an overflowing energy of spirit. He paints, writes poetry, records songs, played the role of Pheidippides in the movie

A Hero’s Journey,

and delivers motivational talks “to get people inspired and alert, so they can discover and utilize the unconditional abilities of human beings, in order to bring (beyond personal improvement) unity, friendship and harmony to the world.”

He has certainly inspired me to push beyond the limits of form. Kouros is not much to look at as a runner, with his boxy build and choppy gait, although little is wasted on his runs, and he keeps moving even while he eats and drinks. His upper body is remarkably muscled. When you look at sprinters, you see those developed upper bodies, too. I think Kouros has found an extra energy source up there in those powerful pectorals and deltoids. Many runners have learned that a strong upper body helps with technique and speed. Kouros, though, seems to have discovered a secret about transferring propulsive power from the arms to the legs.

Ultimately, Kouros teaches us that the ultra is an exercise in transcendence. He explicitly defines it as a test of “metaphysical characteristics,” as opposed to inborn athletic gifts or level of conditioning. Only a continuous run of 24-plus hours will do, “as a runner has to face the whole spectrum of the daytime and nighttime and be able to continue. Doing so, he/she will prove that he/she can run beyond the effectiveness of genetic gifts and fitness level, as these elements will have gone from the duration of time and the muscular exhaustion.” While respecting the athleticism of such events, he disqualifies 50-milers and stage runs from the category of ultra, as they will favor athletes who are well trained and gifted. The true ultrarunner must endure sleep deprivation and complete muscular fatigue. Only then can he or she “find energy after the fuel is gone.”

Reflecting on Kouros’s message and thinking about the bliss that awaited those who could push through an ultramarathon’s pain helped me when, nine days before the event, I woke in the middle of the night and, on my way to the bathroom, stubbed my pinkie toe. The next morning it was black and blue and just hanging there. I was pretty sure it was broken. Over the next week, I tried to tape it against the toe next to it. I tried walking on the beach, bracing the toe with taped Popsicle sticks. I tried a stiffer insole. I told myself that I had almost nine days, that the body could do miraculous things.

At my second Badwater Ultramarathon, in 2006, I experienced the most grueling finish of my running career. I'm grateful that Dusty was with me, making me realize that yes, I could go on.

At my second Badwater Ultramarathon, in 2006, I experienced the most grueling finish of my running career. I'm grateful that Dusty was with me, making me realize that yes, I could go on.

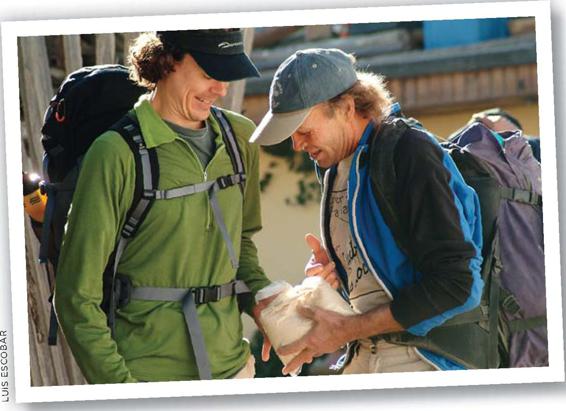

Before heading into the depths of Mexico's Copper Canyon, in 2006, to race the Indians known as the "running people," I met the mysterious race organizer, Caballo Blanco (White Horse). Here we discuss the wondrous properties of pinole.

Before heading into the depths of Mexico's Copper Canyon, in 2006, to race the Indians known as the "running people," I met the mysterious race organizer, Caballo Blanco (White Horse). Here we discuss the wondrous properties of pinole.

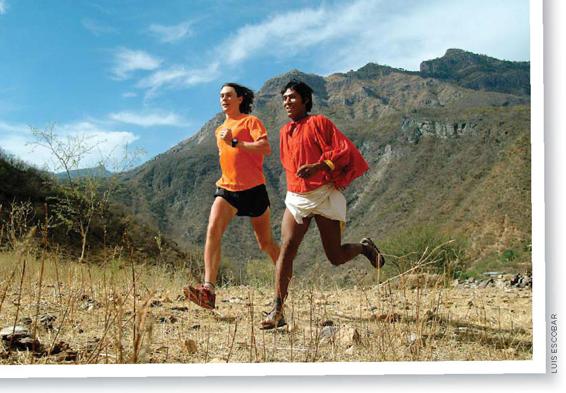

The Tarahumara are known for their grace and speed. The fastest and most graceful of them all is Arnulfo Quimare, and to this day I consider him one of my noblest competitors.

The Tarahumara are known for their grace and speed. The fastest and most graceful of them all is Arnulfo Quimare, and to this day I consider him one of my noblest competitors.

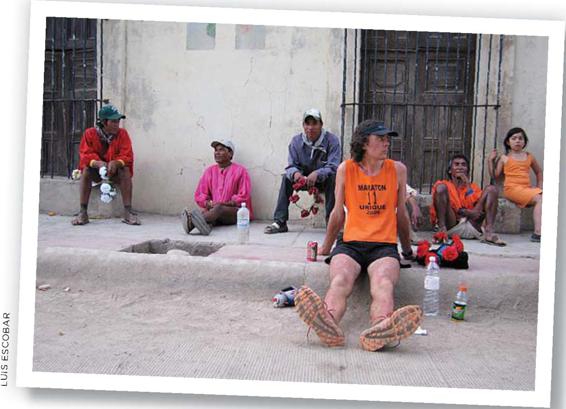

I stay at the finish line to show respect to fellow runners, and because it's a blast. At the conclusion of the 2006 Copper Canyon Ultramarathon, I'm with (L to R) Arnulfo, Manuel Luna, Silvino, Herbalisto, and a local child.

I stay at the finish line to show respect to fellow runners, and because it's a blast. At the conclusion of the 2006 Copper Canyon Ultramarathon, I'm with (L to R) Arnulfo, Manuel Luna, Silvino, Herbalisto, and a local child.

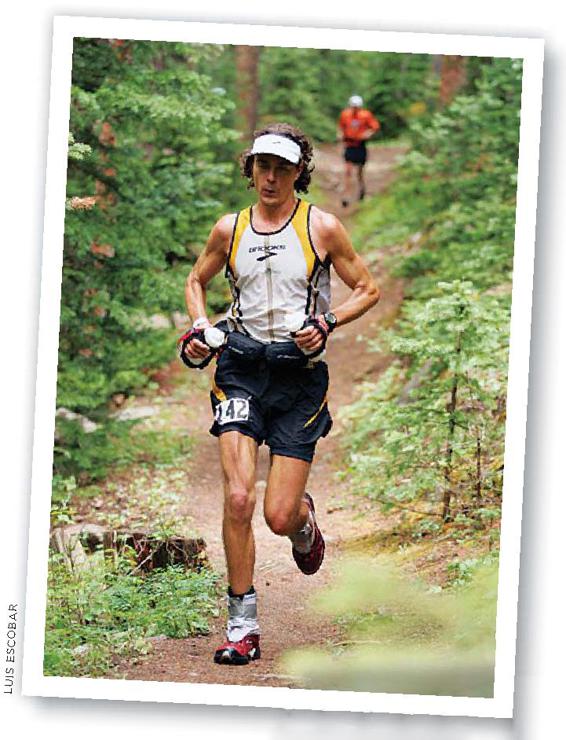

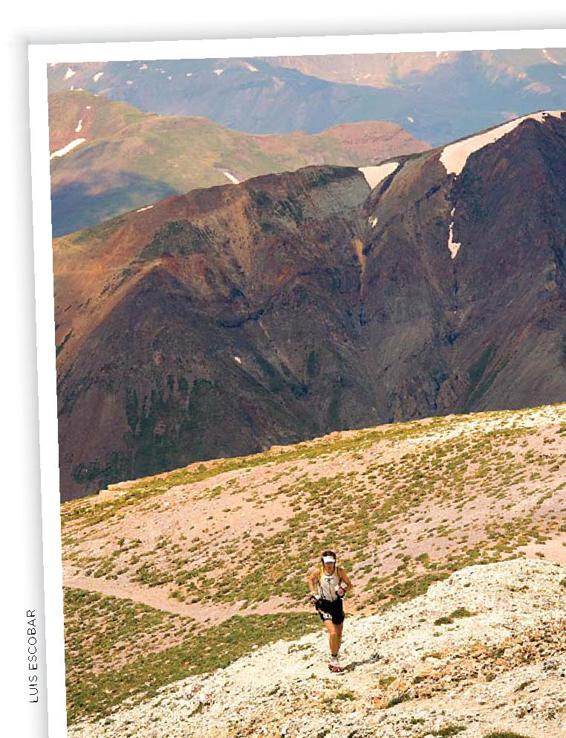

The Hardrock 100 takes runners up 33,000 feet and over eleven mountain passes. In 2007, two nights before the event, I tore the ligaments in my right ankle. The Hardrock suddenly got harder.

The Hardrock 100 takes runners up 33,000 feet and over eleven mountain passes. In 2007, two nights before the event, I tore the ligaments in my right ankle. The Hardrock suddenly got harder.

At the Hardrock 100, runners encounter snow, ice, rain, sleet, and lightning. I'm not sure I ever felt quite as small, or as humbled. If you're an ultrarunner, you can fight nature or embrace it. I suggest the latter.

At the Hardrock 100, runners encounter snow, ice, rain, sleet, and lightning. I'm not sure I ever felt quite as small, or as humbled. If you're an ultrarunner, you can fight nature or embrace it. I suggest the latter.

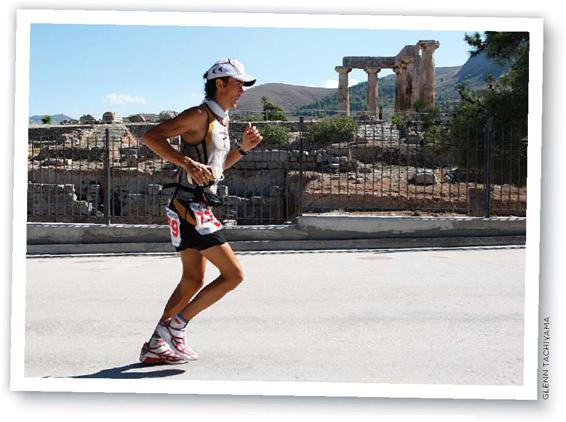

In 2007, in my second Spartathalon victory, as I passed the ruins of Corinth I imagined Pheidippides at my side. Running has taken me places.

In 2007, in my second Spartathalon victory, as I passed the ruins of Corinth I imagined Pheidippides at my side. Running has taken me places.