Early Dynastic Egypt (28 page)

Demanding activities such as construction projects and the maintenance of cults required a disciplined and effective work-force, and a specialised administrative mechanism was employed to maximise the efficiency of work teams. This was the rotational

phyle

system, whose origins go back at least as far as the First Dynasty (Roth 1991).

Expeditions, festivals and the royal boat

A development of great significance at the beginning of the Third Dynasty was the organisation of regular mining expeditions to the Sinai, to obtain supplies of turquoise from the area of the Wadi Maghara. Expeditions under Netjerikhet, Sekhemkhet and Sanakht each left a record of their visit, in the form of a rock-cut scene (Gardiner and Peet 1952: pls I, IV). The inscriptions from the reigns of Netjerikhet and Sekhemkhet depict the expedition leader, complete with titles. In both cases the operation was under the control of the

ỉmỉ-r3 mš ,

‘overseer of the expedition’. An additional member of the Netjerikhet expedition, named as Hemni, was designated as

ỉrỉ-( 3-) 3mwt, ‘

keeper of the (door to the) Asiatics’. He therefore seems to have been responsible in some way for the local (Palestinian) inhabitants of the Sinai. Just as the economic exploitation of the Delta through a network of royal foundations seems to have led to the development of a system of regional administration for Lower Egypt, so Egyptian economic involvement in the Sinai and Near East may have underlain the imposition of more direct state control in the desert and border regions of Egypt (see below).

The titles preserved on the stelae of Merka and Sabef from the reign of Qaa (Emery 1958: pl. 39; and Petrie 1900: pl. XXX, respectively) include unique references to certain royal activities which must have been a feature of the Egyptian court throughout the Early Dynastic period. Qaa clearly enjoyed a lengthy reign, and Sabef was charged with overseeing arrangements for the king’s Sed-festival

(ỉmỉ-r3 hb-sd).

The responsibility for organising this pre-eminent celebration of kingship would have been assigned to a trusted member of the king’s entourage. Sabef s status in this respect is emphasised by his burial

within the king’s own mortuary complex at Abydos. Merka also performed important duties at court. One of these was

h rp wỉ3-nswt,

‘controller of the royal bark’, indicating responsibility for the ship that may have been used by the king on his regular progresses. The character of early kingship seems to have been peripatetic, the monarch travelling throughout Egypt on a regular basis, not only to visit major shrines and take part in important annual festivals but also to reinforce the bonds between ruler and ruled. Royal travel must have played a significant role in the mechanism of early Egyptian administration, and the importance attached to the title ‘controller of the royal bark’ no doubt reflects this.

Courtly titles

As well as employing distinct bureaucracies for particular activities, such as those listed above, the court seems to have comprised numerous officials with general competence rather than specific duties. We should probably envisage a circle of trusted individuals in the service of the king, whose duties were rather fluid and were assigned according to needs and circumstances. These most influential of state employees were probably royal kinsmen, and the titles they bore expressed their proximity to the king, the ultimate source of all authority. Such titles, which we may call ‘courtly’, are the most numerous in Early Dynastic inscriptions. They shed some light on the internal workings of the royal household, but rather more on the nature of early Egyptian administration, which emphasised relative status within the hierarchy more than specific responsibilities.

A good example is

ỉrỉ-p t.

This may have had a specific meaning in the Predynastic period, but by the time it is first attested, in the middle of the First Dynasty (Emery 1958:60, pl. 83.1), it seems to have designated membership of the ruling élite

(p t),

as opposed to the general populace

(rh yt).

More specifically, it is likely that the

p t

were royal kinsmen (Baines 1995:133), for whom the highest echelons of government were reserved until the threshold of the Old Kingdom. On the stela of Merka, from the reign of Qaa (Emery 1958: pl. 39), the title appears in a prominent position, subordinate only to

s(t)m,

indicating the status (and political power?) attached to being an

ỉrỉ-p t

in the First Dynasty.

Another title with possible Predynastic significance is

ỉrỉ-Nh n,

‘keeper of Nekhen’ (cf. Fischer 1996:43–5). When Nekhen (Hierakonpolis) was an important centre, playing a pivotal role in the process of state formation, the ‘keeper of Nekhen’ may have been a prestigious position. By the Early Dynastic period, however, the meaning of the title may have been lost (at least, it is impenetrable to modern scholars), leaving

ỉrỉ-Nh n

as an honorific designation borne by high officials, for example Nedjemankh in the reign of Netjerikhet (Weill 1908:180; Kaplony 1963, III: fig. 324). Two possible courtly titles of unknown meaning from the early part of Den’s reign are

ỉ ,

associated with Ankh-ka and Sekh-ka (Petrie 1900: pls XXI.29, XXII.30; Emery 1958: pls 80–1,106.4) and rp(?), associated with the latter (Petrie 1900: pl. XXII.30; Emery 1958: pl. 106.4).

However, even the reading of the two groups of signs is uncertain, and they may not represent titles at all.

A number of different titles expressed the position of the holder within the circles of power which surrounded the ruler. Merka, at the end of the First Dynasty, was

šms-nswt,

‘a follower of the king’ (Emery 1958: pl. 39), while an official of the Second or Third

Dynasty was content to call himself

hm-nswt,

‘servant of the king’ (Lacau and Lauer 1965:36, no. 47). A parallel title may be the one borne by the king’s sandal-bearer on the Narmer palette and macehead (Winter 1994). In both cases the title may perhaps be read as ‘servant of the ruler’. A more exalted position was indicated by the title

hrỉ-tp nswt,

‘chief one of the king’, mentioned in inscriptions from the late Second and Third Dynasties (Petrie 1901: pl. XXI.165; Junker 1939; Lacau and Lauer 1965:33, no. 43). Akhetaa, who lived during the latter half of the Third Dynasty, appears to have been one of the king’s innermost circle of advisors, if the meaning of his title ‘privy to all the secrets and affairs of the king’

(hrỉ sšt3 nb h t nbt n nswt)

is to be taken at face value (Weill 1908:262–73). (Note, however, that some commentators have identified

hrỉ-sšt3

as a religious title [cf. Fischer 1996:45–9 who reads the title

zhy-n r

].) Pehernefer’s title,

hrỉ-s m,

‘he who has the ear (of the king)’ would also seem to indicate a position at the very centre of the court, even though the king is not mentioned explicitly.

Another category of courtly titles makes reference to particular chambers within the palace as a way of indicating proximity to the king. The titles held by some members of the court in present-day Britain may be cited as parallels, for example, ‘Lord Chamberlain’ (the person having control over many of the royal household’s employees). In ancient Egypt, access to the innermost rooms of the palace must have brought with it access to the person of the ruler, considerable prestige which went with this access, and perhaps real influence in the decision-making processes of government. Titles in this category are attested only in the reign of Qaa and in the Third Dynasty, but they must have existed throughout the Early Dynastic period. Two titles are connected with the running of the palace itself

( h).

The official Merka in the reign of Qaa bore the title

h rp h,

‘controller (perhaps ‘comptroller’ would be a better English equivalent) of the palace’ (Emery 1958: pl. 39). Abneb, who lived in the late Second or early Third Dynasty, held a similar position,

ỉmỉ-r3 h,

‘overseer of the palace’ (Weill 1908:220). Within the palace, two chambers seem to have been of particular significance:

ỉz,

sometimes translated as ‘council chamber’, and

zh,

possibly ‘dining-hall’ or ‘audience chamber’. Thus an

ỉmỉ-ỉz,

‘one who is in the council chamber’ (Lacau and Lauer 1965:16, no. 21), and a

smsw-ỉz,

‘elder of the council chamber’, are known from the Third Dynasty (Gardiner and Peet 1952: pl. I). At the end of the First Dynasty, Merka, as well as being comptroller of the palace as a whole, was also ‘comptroller of the audience chamber’

(h rp zh)

; this title was later held by Pehernefer at the end of the Third Dynasty. Merka’s contemporary, Sabef, described himself as ‘foremost of the audience chamber’

(h ntỉ- zh),

whilst Ankh, an official who lived early in the Third Dynasty, was simply a ‘functionary of the audience chamber’,

( ỉrỉ-h t zh)

(Weill 1908:185).

The vizier

We now come to the position at the very head of the administration, the official closest to the king. At different stages of the Early Dynastic period, this person bore the titles

t

and

t3ỉtỉ z3b 3tỉ

(Figure 4.5). An individual designated as

t

is the earliest attested official of any kind, depicted on the Narmer palette. He walks in front of the king, carrying what appears to be an item of the royal regalia. On the Narmer macehead he appears again, this time standing behind the enthroned king, where he is labelled simply

as

.

The meaning of the title is uncertain, but the position of the holder

vis-à-vis

the king seems clear enough.

It is tempting to link this title with the one borne by the vizier in later periods:

3tỉ,

or in its fuller form,

t3ỉtỉ z3b 3tỉ.

The vizier stood at the head of the Egyptian administration and was responsible directly to the king for the government of the country. The position was certainly in existence by the beginning of the Third Dynasty. The earliest-known holder of the title was a man named Menka who is mentioned on a number of ink inscriptions from beneath the Step Pyramid (Lacau and Lauer 1965:1, no. 1). These may date to the middle of the Second Dynasty (Shaw and Nicholson 1995:15), perhaps to the reign of Ninetjer (Helck 1979). Alternatively, it is possible that the construction of the Step Pyramid, which must have required a degree of administrative organisation and

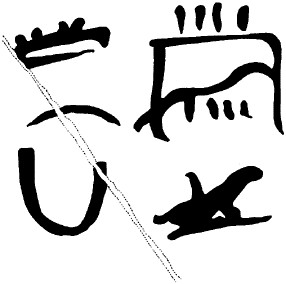

Figure 4.5

The titles of the vizier. The earliest attested reference to the highest administrative office in Egypt, written in ink on a stone vessel from the Step Pyramid complex of Netjerikhet at Saqqara. The inscription, which probably dates to the middle of the Second Dynasty, names the vizier as Menka, and gives the tripartite title associated with the vizierate throughout Egyptian history,

t3ỉtỉ z3b 3tỉ

(after Lacau and Lauer 1965: pl. 1.3).

sophistication previously unknown in Early Dynastic Egypt, necessitated the creation of a new executive post at the head of the government apparatus, to oversee all its activities and report directly to the king. The viziers of the Third and early Fourth Dynasties seem to have been royal princes, perhaps younger sons removed from the direct line of succession. Only in the reign of Menkaura was the position ‘opened up’ to a commoner (Husson and Valbelle 1992:37).

The tripartite title held by a vizier may indicate the threefold nature of his authority. The first element,

t3ỉtỉ,

emphasises the courtly aspect of the office. The literal meaning of

t3ỉtỉ

is ‘he of the curtain’, an epithet reminiscent of positions in the Ottoman court. In Early Dynastic Egypt, it may have carried an ancient significance of which we are unaware. The second element,

z3b,

is usually translated ‘noble’, and was probably no more than a general designation for an official. Some scholars have interpreted the term as expressing the judicial aspect of the vizierate (Husson and Valbelle 1992:37); certainly, in later periods the vizier was the highest legal authority in the land under the king, the ultimate court of appeal (barring an appeal to the king himself), and the official who decided important legal cases. The third part of the title,

t3tỉ,

cannot be translated, but may designate the administrative aspect of the vizier’s office. It is perhaps related to the

t

of Narmer’s reign. The three component elements of the title may originally have been separate and distinct (Husson and Valbelle 1992:36), but it is equally possible that they were used in conjunction from the very beginning, to describe the highest position in the administration.

Other books

Evernight (The Night Watchmen Series Book 2) by Knoebel, Candace

Keeping Watch by Laurie R. King

Alec's Royal Assignment (Man On A Mission Book 3) by Amelia Autin

Rashomon Gate by I. J. Parker

On the Island by Tracey Garvis Graves

Tuff by Paul Beatty

Planilandia by Edwin A. Abbott

Night of the Living Demon Slayer by Angie Fox

Romance in Vegas - Showgirl! by Nancy Fornataro

Blood Never Dies by Cynthia Harrod-Eagles