Early Dynastic Egypt (26 page)

A seal-impression from the tomb of Semerkhet makes reference to

hwt ỉptỉ

(?) (Petrie 1900: pl. XXVIII.77). This may be an estate connected with the queen’s household, since the word

ỉpt

means ‘harem palace’. The institution called

hwt p-Hr-msn

(for example, Lacau and Lauer 1959: pl. 4 no. 21)—also read

hwt p-Hr-w j

(Dreyer

et al.

1996:71)- has been identified as the royal palace, perhaps located in Buto for the king as ruler of Lower Egypt (Weill 1961:135). It is mentioned in inscriptions of the First, Second and Third Dynasties (Lacau and Lauer 1965:80, no. 216; Dreyer

et al.

1996:76, fig. 28, pl.

15.b left, and 72, fig. 25, pl. 14.a). In the reigns of Anedjib and Semerkhet, the estate— perhaps representing the entirety of the palace, its lands and income—bore the king’s name:

hwt p-Hr-msn nswt-bíty Mr-p-bỉ3

and

hwt p-Hr[-msn] iri-nbty,

respectively (Petrie 1900: pls XXVI.58–60, XXVIII.72). A different, though perhaps related, estate is known from the reign of Hetepsekhemwy at the beginning of the Second Dynasty, once again bearing the king’s name:

hwt nswt-bỉty nbty Htp

(Kaplony 1963, III: figs 281–2). The other

hwt

closely associated with the king, the

hwt z3-h3-nb/hwt z3-h3-Hr,

appears in inscriptions from the end of the First Dynasty (Petrie 1900: pls IX.1–2, XXX; Lacau and Lauer 1959: pl. 6 nos 26–9; Dreyer

et al.

1996:75, pl. 15.b right). It too has been

interpreted as the royal residence (Weill 1961:141), but more likely refers to the royal tomb as a separate institution with its own economic demands and administrative apparatus (Roth 1991:166–8).

The treasury and its activities

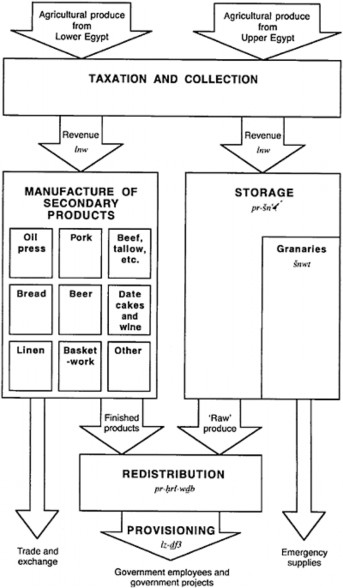

We have seen how Egypt’s agricultural resources were exploited by the court through the mechanism of royal foundations. The actual collection of revenue, its storage, processing and redistribution was the responsibility of a separate institution, the treasury (Figure 4.3). This was the government department which directly managed the income of the state, and as such stood at the very centre of the administration. It was the treasury that assessed and levied taxation, filled the government coffers with agricultural produce, and supplied the various branches of the court with revenue to fund their activities and commodities to sustain their employees.

Taxation and collection

Ink inscriptions on pottery vessels from the late Predynastic period make it clear that, right from the beginning of the Egyptian state, taxation was levied separately on the two halves of the country (Figure 4.4). Inscriptions on vessels from the tomb of ‘Ka’ at Abydos mention either Lower Egyptian or Upper Egyptian revenue (Petrie 1902: pls I- III). A similar division in the collection of produce is attested in the following reigns of Narmer and Aha (Kaplony 1964: figs 1061, 1063; Emery 1939: pls 14 [sic], 20–2). The separate collection of revenue from Upper and Lower Egypt is also indicated by a sealing of Peribsen which mentions the seal-bearer of the Lower Egyptian delivery

(h tmw ỉnw- H3),

probably the individual responsible for the treasury’s income from Lower Egypt (Petrie 1901: pl. XXII.184, 186). As well as highlighting the duality which pervaded Egyptian thought, this binary division in the treasury’s operations probably reflects geographical and topographical factors. The physical difference between Upper and Lower Egypt would have made the collection of agricultural produce a very different undertaking in each region. In Upper Egypt, where the fields are distributed along the narrow floodplain, gathering revenue could have been achieved by a fleet of barges cruising slowly up-or downstream. By contrast, access to the fields of Lower Egypt, spread throughout the Delta, would have been far more difficult. It is quite likely that central collection points would have been established at strategic locations, probably on the major Nile branches. In short, the collection of revenue by the central treasury would have been most efficiently organised by dividing the country into two halves.

This practice may be reflected in the two different names given to the treasury in the Early Dynastic period. Inscriptions mention either the

pr-h ,

‘white house’, or the

pr- dšr,

‘red house’. The former seems to be the earlier name for the treasury and is first attested early in the reign of Den, on seal-impressions from the tomb of Merneith (Petrie 1900: pls XXII.36, XXIII.40). Towards the end of the First Dynasty, for reasons

Figure 4.3

The treasury and its functions. The chart shows the principal operations carried out by the treasury in the Early Dynastic period (based upon information from contemporary sources: seal-impressions,

inscribed stone vessels, and the Third Dynasty tomb inscription of Pehernefer).

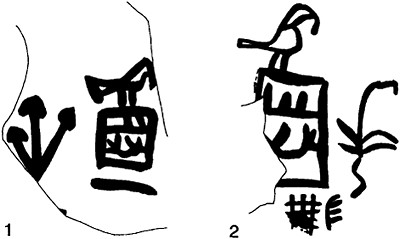

Figure 4.4

Taxation. Ink inscriptions of King ‘Ka’ on cylinder vessels from his tomb complex at Abydos. They record produce received by the royal treasury through separate taxation of (1) Lower Egypt and (2) Upper Egypt (after Petrie 1902: pls 1.2, 111.30). These inscriptions provide evidence for the early division of Egypt into two units for administrative purposes.

which are unclear, the name for the treasury was changed to

pr-dšr.

This institution is attested in the reigns of Anedjib (Petrie 1900: pl. XXVII.68), Qaa (Petrie 1900: pls XXIX.85, XXX) and Ninetjer (Lacau and Lauer 1959: pl. 14 no. 70; Kaplony 1963, III: figs 746, 748). With the accession of Sekhemib/Peribsen, the name reverted

to pr-h

(Petrie 1901: pls XXI.167, 169, and XXII.182, 183), only to be changed back to

pr-dšr

under Khasekhemwy (Petrie 1901: pl. XXIII.191, 192, 196). The name remained

pr-dšr

during the reign of Netjerikhet (Kaplony 1963, III: fig. 318), and was changed for the last time under his successor Sekhemkhet to

prwỉ-h ,

‘the two white houses’ (Goneim 1957:14–15), perhaps reflecting an amalgamation of two previously separate institutions. Because the colours white and red are also the colours of the Upper and Lower Egyptian crowns respectively, it is tempting to see the

pr-h

as an Upper Egyptian institution, the

pr-dšr

as its Lower Egyptian counterpart. The two names would then reflect the logical division of the treasury’s operations into two halves. However, the two seem never to have coexisted, so the preference given to one name or the other might reflect the central administration’s shifting centre of gravity. The initial change from

pr-h

to

pr-dšr

might indicate a relocation of the state redistributive apparatus to Memphis in the latter part of

the First Dynasty. The continued use of the name

pr-dšr

by the kings of the early Second Dynasty certainly complements the location of their tombs at Saqqara and the general Lower Egyptian emphasis of the court at this time. The change of name back to the older

pr-h

under Sekhemib/Peribsen ties in with the Upper Egyptian emphasis of his reign: Peribsen re-adopted Abydos as the site of the royal mortuary complex and he is attested only in Upper Egypt. The final change in nomenclature (to

prwi-h )

under Sekhemkhet possibly indicates an ideological compromise, reconciling the competing traditions of Upper and Lower Egypt in a new, unified institution.

Storage

Inscriptions of the Second Dynasty mention a sub-department of the treasury called the

pr-šn

(Lacau and Lauer 1959: pl. 18 no. 90; Kaplony 1963, III: fig. 367). The derivation of the word is not altogether clear, but it seems to have been either the department responsible for (corvée?) labour or, more likely perhaps, the department charged with the storage of agricultural produce prior to its redistribution. The

pr-šn

would then have comprised large-scale storage facilities and would probably have managed the government surpluses held in long-term storage—for example, the ‘buffer’ stocks of grain—as well as the produce received in the form of taxation and later redistributed.

Cereals were probably the staple crops of Egyptian agriculture in the Early Dynastic period, as in later times, and grain supplies must have lain at the heart of the treasury’s operations. The storage of large stocks of grain was a vital necessity, not only to pay the court itself with its hundreds of dependent officials, but also to guard against years with poor harvests. At such times, the emergency supplies held by the government provided the only security for ordinary Egyptians, the vast majority of whom were peasant farmers. The ability of the government to provide a degree of economic security must have brought real benefits to the Egyptian population, and would have been one of the most tangible benefits of a united country with a centrally controlled economy. Curiously, the central government granaries are not explicitly attested before the Third Dynasty, although they must have existed from the very beginning of the Egyptian state, perhaps under a different department of the treasury. They may have been an integral part of the

pr-h /pr-dšr

in the first two dynasties, only to be given separate status at the beginning of the Third Dynasty. Granaries are mentioned on a seal-impression of Sanakht from Beit Khallaf (Garstang 1902: pl. 19.7; Seidlmayer 1996b: pl. 23), while the official Pehernefer was ‘overseer of all the king’s granaries’

(ỉmỉ-r3 šnwt nb nt nswt)

at the end of the Third Dynasty (Junker 1939).

Redistribution

Another institution closely connected with the operations of the treasury was the

pr-hrỉ- w b,

the ‘house of redistribution’ (sometimes translated ‘house of largesse’). This is attested from the reign of Khasekhemwy (Petrie 1901: pl. XXIII.197) and is mentioned quite frequently in official sources of the Third Dynasty (for example, Junker 1939). The

pr-hrỉ-w b

was probably the department of the treasury directly responsible for the redistribution of agricultural produce to recipients throughout Egypt, including state

employees and provincial cults (Gardiner 1938:85–9; Malek 1986:35; but note Warburton 1997:72). Standing at the centre of the state economic apparatus, the

pr-hrỉ- w b

must have been a key department of the Early Dynastic administration.

Provisioning

An important activity connected with the collection and redistribution of income is attested from the reign of Sekhemib/Peribsen. This is

ỉz- f3,

the ‘provisioning department’ (Petrie 1901: pl. XXI.165). It seems to have acted as a constituent department of the treasury, whether the

pr-h

under Sekhemib/Peribsen (Petrie 1901: pl. XXI.167, 174, pl. XXII.183) or the

pr-dšr

under his successor Khasekhemwy (Petrie 1901: pl. XXIII.192). A provisioning department of the

pr-nswt

is also attested in the reign of Khasekhemwy (Petrie 1901: pl. XXIII.201), indicating that this administrative innovation was not restricted to the management of state income but was applied equally to the personal economic resources of the king. At the end of the Second and beginning of the Third Dynasty, seal-impressions mention a provisioning department connected with the vineyards of Memphis (Kaplony 1963, III: figs 310, 318).

Manufacture of secondary products

The treasury was not only responsible for the collection, storage and redistribution of income in the form of agricultural produce, it also controlled the manufacture of secondary products from these primary commodities. Products such as oil and meat, bread and beer, were required for the provisioning of the royal household and the court in general. The manufacture of secondary products seems to have been divided amongst a number of specialist departments. Some of these are attested from the First and Second Dynasties. Many more are listed in the tomb inscription of Pehernefer at the end of the Third Dynasty.

Other books

Finding Noel by Richard Paul Evans

The Pirates! in an Adventure with the Romantics by Gideon Defoe

Johnston - Heartbeat by Johnston, Joan

The Temporary Mrs. King by Maureen Child

Striking the Balance by Harry Turtledove

The Mighty and Their Fall by Ivy Compton-Burnett

The Troll Whisperer by Sera Trevor

The Wild Girls by Ursula K. Le Guin

American Made (Against the Tides #2) by Katheryn Kiden

The Wife of a Lesser Man (LA Cops Series Book 1) by Sandy Appleyard