Early Dynastic Egypt (12 page)

Taking into account all the evidence, it is possible to suggest the following hypothetical reconstruction of events leading to the political unification of Egypt. As early as Naqada I, powerful centres had developed at This, Naqada and Hierakonpolis in Upper Egypt, whilst local élites at other sites exercised varying degrees of economic and political control over their respective territories. During the course of Naqada II (

c.

3400 BC), powerful local rulers are attested at Abadiya (Kaiser and Dreyer 1982:244; Williams 1986:173) and Gebelein, but it was the three major centres and their ruling families that continued to dominate the processes associated with state formation. Towards the end of Naqada II, a flourishing polity arose in Lower Nubia, ruled by kings who shared the emergent iconography of rule with their counterparts in Upper Egypt. At some point early in Naqada III, the Predynastic kingdom of Naqada was probably incorporated—whether by political agreement or by military force cannot be established—into the territory of a neighbouring kingdom. The amalgamation of these two polities would then have preceded the unification of Upper Egypt as a whole (F.A.Hassan 1988:165). The Cairo fragment of the Palermo Stone shows, in the top register, a line of kings wearing the

double crown

(hand copy by I.E.S.Edwards in the library of the Faculty of Oriental Studies, Cambridge University; cf. Trigger

et al.

1983:44 and 70). If the red and white crowns originated at Naqada and Hierakonpolis respectively, then these figures—often interpreted as kings of a united Egypt before the beginning of the First Dynasty—may represent rulers of an Upper Egyptian polity comprising the territories of Hierakonpolis and Naqada. Furthermore, the adoption of the local god of Hierakonpolis, Horus of Nekhen, as the supreme deity of kingship, and the special attention paid to the temple of Horus by early kings, suggests that it was the rulers of Hierakonpolis who made the first move in the game of power-play that was ultimately to lead to the unification of Egypt. The annexation of Naqada would explain the gap in the sequence of élite burials at the site at the end of Naqada III, a period which is marked at Hierakonpolis by the large tombs at Locality 6. Alternatively, Naqada may have been eclipsed by its northern rival: despite the undoubted importance of Hierakonpolis, the unparalleled size of Abydos tomb U-j (slightly earlier in date than the élite tombs at Hierakonpolis Locality 6) suggests that the kingdom of This was already dominant by early Naqada III, at least in the northern part of the Nile valley. Perhaps the ruler of This also exercised hegemony over Lower Egypt by this time, giving him access to the foreign trade which is so dramatically attested in the imported vessels buried in his tomb. Nevertheless, it is still possible that several rulers, each with his own regional power- base, continued to co-exist and to claim royal titles. This may account for a number of the royal names attested at the end of the Predynastic period.

It is not clear how politically advanced the Delta was in late Predynastic times. A more hierarchical social structure may have developed rapidly in the wake of Upper Egyptian cultural influences which permeated Lower Egypt in late Naqada II (von der Way 1993:96). There were probably powerful local élites at several sites, notably Buto and Saïs. Some Lower Egyptian rulers may have adopted elements of early royal iconography, particularly the

serekh

, since many of the vessels incised with

serekh

marks have a Lower Egyptian provenance (Kaiser and Dreyer 1982: figs 14 and 15). It is quite likely that the Upper Egyptians who spearheaded the drive toward political unification had to overcome or accommodate local Lower Egyptian rulers. None the less, we cannot discount the possibility that the Delta had been incorporated into a larger polity centred on This by the Naqada III period (c. 3200 BC). Certainly it was the rulers of This who ultimately triumphed in the contest for political power and claimed the prize of kingship over the whole country, even though Hierakonpolis seems to have remained important until the very end of the Predynastic period. Control of Lower Egypt would undoubtedly have given the Thinite rulers a major advantage over their southern rivals.

Given that King ‘Scorpion’ dedicated his ceremonial macehead in the temple at Hierakonpolis, and that he is not attested at Abydos, the theory that he belonged to the royal house of Hierakonpolis is an attractive one. If this was the case, there may have been two rival polities governed from This and Hierakonpolis up to the very threshold of the First Dynasty. The reverence shown to Hierakonpolis by the Early Dynastic kings may reflect the site’s importance during the final stages of state formation. The end of Scorpion’s reign may have marked a decisive turning-point, the moment at which the king of This assumed an uncontested position as sovereign of all Egypt. During the peak of activity that accompanied political unification, Egyptian control was extended beyond the borders of Egypt proper into Lower Nubia, crushing the local kingdom centred at Qustul and leading to the rapid disappearance of the indigenous A-Group culture. Military raids by early Egyptian rulers are commemorated in two rock-cut inscriptions at Gebel Sheikh Suleiman in the Second Cataract region (Needier 1967; Murnane 1987). Egyptian ‘colony sites’ also seem to have been established in southern Palestine, suggesting a degree of political control, or at least influence, in the region. The final stages of state formation may have been accomplished quite quickly, within two or three generations, and Narmer may, after all, have been the first king to exercise authority throughout the country unchallenged. He seems to have been regarded by at least two of his successors as something of a founder figure (Shaw and Nicholson 1995:18). It remains impossible to define the moment at which a single king ruled Egypt for the first time. From the evidence, this must have occurred at some point between the lifetime of the owner of Abydos tomb U-j (

c.

3150 BC) and the reign of Narmer (

c.

3000 BC) (cf. Malek 1986:26). Many scholars favour an earlier rather than a later date for political unification, but the evidence is by no means unanimous.

The actual means by which the rulers of This ultimately gained control over the whole country is not known. Annexation of neighbouring territories must have involved negotiation and accommodation at the very least. It is not unlikely that more forceful tactics were required, and the possibility of military action cannot be ruled out, despite the difficulties involved in interpreting monuments like the Narmer Palette. The ‘Libyan Palette’ depicts attacks on a number of fortified cities (Petrie 1953: pl. G; Kemp 1989:50, fig. 16; Spencer 1993:53, fig. 33), but again the symbolism of the decoration may not be

straightforward. However, the campaigns of Khasekhem against northern, perhaps Lower Egyptian, rebels at the end of the Second Dynasty may provide a later parallel for the sort of action that was required to subjugate the Delta.

KINGS BEFORE THE FIRST DYNASTY

As we have seen, there is convincing evidence for the emergence of at least three Upper Egyptian polities by the Naqada II period (

c.

3500 BC). The sites of This (with its cemetery at Abydos), Naqada and Hierakonpolis appear to have stood at the centres of powerful territories, each ruled by an hereditary élite exercising authority on a regional basis. The rulers of the three territories—plus an individual buried at Gebelein, who may have controlled a smaller area—used recognisably royal iconography to express the ideological basis of their power, and may justifiably be called ‘kings’. However, the respective owners of the Abydos vessel, the tombs in Naqada Cemetery T, the Hierakonpolis painted tomb and the Gebelein painted cloth are anonymous. Whilst their status is clear, they are quite literally prehistoric, having left no written evidence. It has been proposed that these kings exercising only regional authority might be grouped together as ‘Dynasty 00’ (van den Brink 1992a: vi and n. 1), recognising their royal status but emphasising their place in prehistory. The term is perhaps rather contrived, and has not won general acceptance. None the less, the place of these late Predynastic anonymous rulers at the head of the later dynastic tradition should be acknowledged.

History begins with the advent of written records, in Egypt’s case the bone labels from Abydos tomb U-j. Despite the number of inscribed labels from the tomb, the name of the owner himself is not certain. Several pottery vessels from U-j were inscribed in ink with the figure of a scorpion (Dreyer 1992b: pl. 4), and this has been interpreted as the owner’s name, not to be confused with the later King ‘Scorpion’ who commissioned the ceremonial macehead found at Hierakonpolis (Dreyer 1992b: 297 and n. 6, 1993a: 35 and

n. 4). Other vessels from tomb U-j bear short ink inscriptions consisting of a combination of two signs (Dreyer 1995b: 53, fig. 3.a-d). Some of the inscriptions have one sign in common, interpreted by the excavator as a stylised tree, perhaps indicating ‘estate’. It has been suggested that the accompanying sign in each case is a royal name, giving the sense ‘estate of King X’ (Dreyer 1992b: 297, 1993a: 35, 1995b: 52 and 54). This hypothesis is based upon later parallels which may not be appropriate to the Naqada III period, and the identification of a large number of new royal names on vessels from a single tomb may be questioned. However, many scholars accept the hypothesis, even if the existence of late Predynastic kings called ‘Fish’ and ‘Red Sea shell’ seems somewhat unlikely.

‘Dynasty 0’

Subsequent kings of the Thinite royal family were interred in the same ancestral burial ground, those rulers prior to Djer being buried in the section known to modern scholars as Cemetery B. The name of at least one pre-First Dynasty king is known, whilst inscriptions on vessels and on rocks in the eastern and western deserts attest the existence of further named kings before the reign of Narmer (Figure 2.3). Other inscriptions which may or may not be kings’ names have also come into the discussion. It is these rulers that

collectively constitute ‘Dynasty 0’. The term has caused some confusion, and it is rather unhelpful as the word ‘Dynasty’ suggests a single ruling line, moreover one which exercised control over the whole of Egypt. The various names undoubtedly represent rulers of various polities from different regions of the country, and it is practically impossible to establish which king was the first to rule over the whole of Egypt. However misleading it may be, the term ‘Dynasty 0’ has nevertheless come into general use and is unlikely to be discarded. A preferable and more neutral term might be ‘late Predynastic kings’.

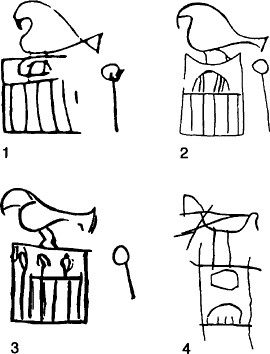

Figure 2.3

Kings before the First Dynasty. Royal names of four late Predynastic rulers, incised on pottery vessels to indicate royal ownership of the contents: (1)

serekh

of ‘Scorpion’ (after Kaiser and Dreyer 1982:263, fig. 14.34); (2)

serekh

of ‘Ka’ (after Kaiser and Dreyer 1982:263, fig.

14.23); (3)

serekh

of unidentified King A (after van den Brink 1996: pl. 30.a); (4)

serekh

of unidentified King B (after Wilkinson 1995:206, fig. l.b). Names not to same scale.

Several tall storage vessels from Tura and el-Beda (at the western end of the north Sinai coastal route) are incised with the motif of a

serekh

surmounted by two falcons (Junker 1912:47, fig. 57.5; Clédat 1914; van den Brink 1996: table 1 nos 5–6, pl. 25.a). Some scholars have suggested that this represents the name of a particular late Predynastic ruler, perhaps based in Lower Egypt (von der Way 1993:101). It could equally be a mark designating royal ownership without specifying the ruler in question.

The more famous of the two rock-cut inscriptions at Gebel Sheikh Suleiman in Lower Nubia shows an early

serekh

presiding over a scene which apparently records a punitive Egyptian raid into the Second Cataract region at the end of the Predynastic period. Once erroneously dated to the reign of Djer, the inscription has now been shown conclusively to date to the period of state formation (Murnane 1987; cf. Shaw and Nicholson 1995:86). The

serekh

is empty and therefore anonymous, but we may hazard a guess that the ruler who ordered the inscription to be cut was an Upper Egyptian king, perhaps based at Hierakonpolis. The Gebel Sheikh Suleiman inscription proves that Egyptian military involvement in Lower Nubia—probably aimed at maintaining Egyptian access to sub- Saharan trade routes—began before the start of the First Dynasty. The process of Egyptian expansionism which led to the collapse of the Qustul kingdom and the disappearance of the indigenous A-Group culture may therefore have lasted several generations (cf. Williams 1986:171).

Other books

Terminal Connection by Needles, Dan

Heart of Glass by Dale, Lindy

Hammer by Chelsea Camaron, Jessie Lane

Perfect Sacrifice by Parker, Jack

Flowers in the Snow by Danielle Stewart

Reinventing Mike Lake by R.W. Jones

The Heart Doctor and the Baby by Lynne Marshall

Act of Will by Barbara Taylor Bradford

Postcards From Tomorrow Square by James Fallows

Going for Four: Counting on Love, Book 4 by Erin Nicholas