Early Dynastic Egypt (58 page)

Khnum

A ram deity, possibly Khnum, is one of the elements composing a personal name on a private stela from Abydos dating to the reign of Djer (Petrie 1901: pl. XXVI.62) and one from the following reign of Djet (Petrie 1902: pl. XIII.151). Another theophorous personal name, read as Khnum-hotep, occurs on a sealing from the tomb of Merneith (Petrie 1900: pl. XXIII.42). Numerous inscribed stone vessels from the galleries beneath the Step Pyramid bear the personal name Iy-en-khnum (Lacau and Lauer 1965:3–8, pls 2–9 [nos 2–8]) and this individual probably lived during the reign of Ninetjer (Kahl 1994:880; Faltings and Köhler 1996:100, n. 52). An even closer devotion to the god is expressed in the personal name

H nmw-ỉt(=ỉ),

‘Khnum is (my) father’, inscribed on another stone vessel from the Step Pyramid hoard (Lacau and Lauer 1965:49, pl. 29.3 [no. 95]). An incomplete First Dynasty plaque of glazed composition from the early temple at Abydos shows a ram holding a

was

-sceptre. The figure is accompanied by a complex jumble of hieroglyphs, the interpretation of which is difficult, but the ram may be Khnum (Petrie 1903: pls I, V.36).

Mafdet

A stone vessel fragment from the tomb of Den at Abydos shows the fetish of the feline goddess Mafdet (Petrie 1901: pl. VII.7). Possibly from the same reign, another inscribed stone vessel shows Mafdet as a lioness, though clearly identified by name; the left-hand fragment was found in the tomb of Den at Abydos (Petrie 1901: pl. VII. 10), but the right-hand fragment was found in the neighbouring tomb of Semerkhet (Petrie 1900: pl. VII.4). (For the two fragments joined see O’Connor 1987:35, fig. 14.) A fragmentary sealing from the tomb of Den also shows the fetish of Mafdet (Petrie 1900: pl. XXXII.39). The importance of the goddess in the reign of Den is emphasised by an entry

for this king on the Palermo Stone: one of the eponymous events of Den’s year x+13 is the fashioning or dedication of a divine image of Mafdet (see Figure 8.6 for all these illustrations). Since an image of Seshat was dedicated in the same year, there may have been a connection between the two goddesses, though this is by no means certain.

In the Pyramid Texts, Mafdet is referred to as a killer of snakes (Utterance 295 [§438]) (Gardiner 1938:89), and more particularly as the

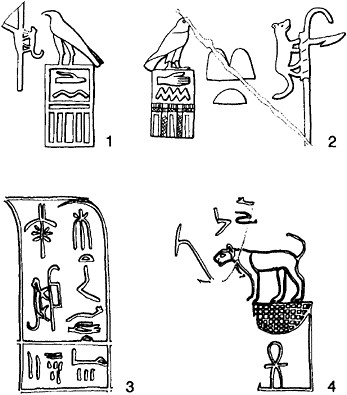

Figure 8.6

The goddess Mafdet. Represented as a feline, Mafdet may have acted as guardian of the king in the palace. Her cult appears to have enjoyed particular prominence during the reign of Den: (1) seal- impression of Den from Abydos, showing the fetish of Mafdet (after Petrie 1900: pl. XXXII.39); (2) relief inscription on a stone vessel from the tomb of Den at Abydos, showing the fetish of the goddess Mafdet (after Petrie 1901: pl. VII.7); (3)

entry from the third register of the Palermo Stone, referring to a year in the reign of Den as ‘the year of dedicating an image of Mafdet’ (after Schäfer 1902: pl. I); (4) inscription depicting and naming Mafdet, on a stone vessel from Abydos, dating to the reign of Den (after Petrie 1900: pl. VII.4; Petrie 1901: pl. VII.10).

Not to same scale.

protectress and avenger of the king (Utterance 297 [§440–1]). The points of the harpoon with which the king decapitates his adversaries are likened to ‘the claws of Mafdet’ (Utterance 519 [§1212]). Mafdet may have held a special place in the sphere of kingship during the Early Dynastic period, perhaps responsible for the purely physical well-being of the king (Westendorf 1966:131–5). As

nbt hwt nh ,

‘mistress of the estate (or mansion) of life’, Mafdet may have been considered as the protecting power of the royal court. In the Early Dynastic period the ‘Estate of Life’ may have designated the living- quarters of the royal palace (Gardiner 1938:89), or perhaps more specifically ‘the royal eating and food storage areas’, and Mafdet may have been embodied in the cats which probably protected these facilities against snakes and vermin (O’Connor 1987:35). Another suggestion is that Mafdet was originally a tamed big cat (possibly a leopard used for hunting) who escorted the ruler, protecting him and at the same time symbolising his silent power and strength (Westendorf 1966:131–5). The fetish of Mafdet shows execution equipment, and the goddess is thus regarded as a manifestation of judicial authority (Lurker 1980:79). The connection may be that, as the deity symbolic of royal power, she led rebels to their execution.

Mehit

A deity associated with Hierakonpolis and (primarily) This (Emery 1961:125), Mehit is depicted as a recumbent lioness with three bent poles projecting from her back. Mehit occurs on a number of Early Dynastic sealings (for example, Petrie 1901: pl. XVI.116), always preceding a depiction of the archetypal Upper Egyptian shrine, the

pr-wr.

Mehit may have been a general protector deity, associated with holy places. It is quite possible that, like Horus the Behdetite, the lioness goddess later identified as Mehit was not, at first, attached to a particular locality.

Min

The colossal statues of a fertility god found in the temple at Coptos indicate that the cult of the deity later named as Min was important from Predynastic times (Payne 1993; cf. Kemp 1989:81, fig. 28; Dreyer 1995b). Although in origin a local deity of Coptos (which always remained the god’s principal cult centre), Min probably enjoyed a national significance from an early period. The tradition in the Late Period that Min ruled Egypt at the beginning of history—a myth which linked Min with the first ‘historic’ King

Menes—may preserve echoes of the god’s importance during the period of state formation (Hornung 1983:108). The ‘thunderbolt’ symbol of Min, also attested from the Predynastic period, occurs on the Scorpion macehead, on a divine standard. Two such symbols are depicted flanking the head of Bat on a decorated ivory plaque from Early Dynastic Cemetery 300 at Abu Rawash (Klasens 1958:50, fig. 20(y), 53, pl. XXV). The symbol is also shown on a private stela from the reign of Djer (Petrie 1901: pl. XXVI.68) and on a sealing from the tomb of Merneith at Abydos (Petrie 1901: pl. XVII.135). It has been suggested that, like other prominent deities, Min may originally have been a god associated with the celestial realm, in this case the phenomenon of thunder (Wainwright 1941:30). The Palermo Stone records the fashioning or dedication of an image of Min as the eponymous event of year 7 of an unidentified First Dynasty king. An identical entry is given for year 6 of Semerkhet (on the main Cairo fragment), and for year 3 of an unidentified Third Dynasty king. A fragment of a slate bowl from the tomb of Khasekhemwy is inscribed in ink with the figure of Min (Petrie 1902: pl. III.48). Identical inscriptions were found in the galleries beneath the Step Pyramid, indicating that both sets of funerary provisions were drawn from the same source (Lacau and Lauer 1965: pl. 15.1–5). The full text gives the legend

pr Mnw,

‘estate of Min’, showing that the cult of Min was flourishing and in receipt of royal patronage at the end of the Second Dynasty.

Neith

Neith was a warlike goddess whose name perhaps means ‘the terrifying one’. Her symbol, the crossed arrows, occurs as early as the Predynastic period, and Neith was clearly an important deity at the very beginning of the Early Dynastic period, with a ‘dominant role at the royal court’ (Hornung 1983:71). ‘Neith’ is thus a common element in the theophorous names of Early Dynastic queens (cf. Weill 1961, chapter 13), notably Neith-hotep (the wife of Narmer), Herneith (possibly a wife of Djet) and Merneith (the mother of Den and regent during his minority). Personal names incorporating the name of Neith are also common amongst the retainers buried in the subsidiary graves surrounding the royal tombs at Abydos from the reign of Djer (Petrie 1900: pl. XXXI.9 [tomb Z], 10 [tomb W51], 11 [tomb W58], 20 [tomb T], pl. XXII.14). A label of Aha seems to record a royal visit to the shrine of Neith. This was probably located at Saïs in the north-western Delta, the principal cult centre of Neith in historic times (Petrie 1901: pl. IIIA.5). (The inscription of Wadj-hor-resne, recording the restoration of the temple of Neith at Saïs during the Persian period, speaks of the antiquity of the temple and its cult [Lichtheim 1980:36–41].) One of Merka’s numerous titles was

hm-n r Nt,

‘priest of Neith’. The reverence shown to the cult of Neith by the early kings of Egypt and their wives may reflect the importance of the Delta, and of Saïs in particular, in the process of state formation.

Neith clearly remained important during the Second Dynasty, An inscribed stone bowl from the Step Pyramid complex shows the figure of the goddess in front of the

serekh

of Ninetjer, with an estate of Nebra also named (Lacau and Lauer 1959:14, pl. 16 no. 77). A Second Dynasty princess bore the name Neith-hotep (Lacau and Lauer 1959: pl. 21, no. 112), while a phyle (or more likely, perhaps, its head priest) was called

hm Nt,

‘servant of Neith’ (Lacau and Lauer 1959:17, pl. 21 no. 116).

Nekhbet

The name Nekhbet simply means ‘she of Elkab’, and the main cult centre of the goddess was located at this site in southern Upper Egypt. However, from the very beginning of Egyptian history, Nekhbet assumed an additional, national importance as tutelary goddess of the whole of Upper Egypt. Depicted as a vulture, Nekhbet joined the cobra goddess of Buto, Wadjet, to form the Two Ladies’, divine protectresses of the Two Lands. The balance of opposites which Nekhbet and Wadjet embodied led to the inclusion of the Two Ladies’ in the formal titulary of the king, from at least the reign of Semerkhet. The earliest surviving depiction of the Two Ladies’ occurs somewhat earlier, on the celebrated ebony label from the tomb of Neith-hotep at Naqada, dating to the reign of Aha. Rock-cut inscriptions of Qaa near Elkab also show the figure of Nekhbet, and there is a reference to the goddess on the Palermo Stone in regnal year x+14 of Ninetjer. The incorporation of various important local deities (such as Nekhbet, Wadjet and Seth) into early royal titulary and iconography seems to have been one of the means by which the unity of the new state was promoted on a psychological level. It thus forms a key component of the mechanisms of rule developed by Egypt’s Early Dynastic rulers.

Osiris (?)

Although the god Osiris is not attested by name until the Fifth Dynasty Pyramid Texts, the probable antiquity of many of these texts makes it not unlikely that he was recognised at an earlier period, perhaps under the name Khentiamentiu. A central element of the later Osiris myth, the pairing of Horus and Seth, is attested from the middle of the First Dynasty, ‘antedating the first attestations of Osiris by six centuries or more’ (Quirke 1992:61). It may be significant that two ivory objects in the form of the

djed

-pillar

, later one of the emblems associated with Osiris, were found amongst the grave goods in a First Dynasty tomb at Helwan (Saad 1947:27, pl. XIV.b).

Ptah

Later revered as the god of craftsmen, Ptah was always closely associated with the royal capital, Memphis. Manetho records that Menes, the legendary first king of Egypt, built a temple to Ptah at Memphis, but it is possible that a local cult of Ptah existed in the area before the beginning of the First Dynasty. The first definite attestation of Ptah is on a travertine bowl from tomb 231 at Tarkhan, dated to the middle of the First Dynasty, possibly the reign of Den (Petrie

et al.

1913:12, 22, pls III.l, XXXVII). The figure of the god in his shrine is accompanied by the name ‘Ptah’, making the identification certain. A sculptor named Peh-en-Ptah is mentioned on a stone vessel from the tomb of Peribsen at Abydos (Amélineau 1905: pl. L.2) and on several similar vessels from the Step Pyramid complex at Saqqara (Lacau and Lauer 1959: pl. 25, nos 140–5).

Ra(?)

An ivory comb of Djet from Abydos shows a pair of outstretched wings and above them a falcon in a bark. This is the first known representation of a deity travelling across the sky in a bark, a common image in later religious iconography (cf. Hornung 1983:227). It

may be assumed that the falcon represents a cosmic deity, and more specifically the sun god ‘since the sun is the principal heavenly body that moves across the heavens’ (Quirke 1992:22). However, in the first two dynasties it is possible that the word

r

was used to denote the sun as an object rather than the name of a deity. Hence, the name of the Second Dynasty king may be read as Nebra, ‘Lord of the sun’, rather than Raneb, ‘Ra is (my) lord’ (Quirke 1992:22). Otherwise, the earliest depiction of the solar disc in a context where it may symbolise a deity is on a sealing of Peribsen from Abydos. Here, the sun disc appears above the Seth-animal, possibly suggesting an association between the two gods, perhaps even an early example of syncretism (Petrie 1901: pl. XXI.176).

Other books

In The Wreckage: A Tale of Two Brothers by Simon J. Townley

The Killer by Jack Elgos

Black Legion: 02 - Assault on Khorram by Michael G. Thomas

StarMan by Sara Douglass

Know Not Why: A Novel by Hannah Johnson

Chump Change by G. M. Ford

Too Close To The Fire/Too Hot To Handle (Montana Men 3) by Jaydyn Chelcee

Memoria del Fuego. 1.Los nacimientos.1982 by Eduardo Galeano

Verum by Courtney Cole