Dream boogie: the triumph of Sam Cooke (108 page)

Read Dream boogie: the triumph of Sam Cooke Online

Authors: Peter Guralnick

Tags: #African American sound recording executives and producers, #Soul musicians - United States, #Soul & R 'n B, #Composers & Musicians, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #BIO004000, #United States, #Music, #Soul musicians, #Cooke; Sam, #Biography & Autobiography, #Genres & Styles, #Cultural Heritage, #Biography

After a Scripture reading by Reverend Charles and a brief prayer, Bumps’ longtime gospel protégé, Bessie Griffin, got up to sing, but she was barely able to get out of her seat before she was overcome with such intensity of emotion that she had to be carried out. There was momentary confusion, and then Ray Charles, sitting on the edge of the roped-off family section, stood up, the

Los Angeles Sentinel

reported, and “asked to ‘see’ the body of his slain friend for the last time.” Standing by Sam’s casket, he asked the crowd what they wanted him to do. “Sing!” the response came back. And he sat down at the piano and sang “Angels Keep Watching Over Me” as J.W. leaned over, gravely holding the mike. “I gave my heart to it,” said Ray, whose career almost perfectly mirrored Sam’s, each encountering bitter criticism when he “crossed over,” in Ray’s case by introducing gospel sounds to a pop setting, in Sam’s by embracing pop. “The song itself I loved, because it was so true. ‘All night and all day / All day and all night / The angels keep watching over me.’ You know, that says so much, and that’s what I felt about him. I tried to sing it in such a way that he would be proud. Sam had a uniqueness about him. Nobody sound like Sam Cooke. I mean

nobody.

He hit every note where it was supposed to be, and not only hit the note but hit the note with feeling. Everything that came out of me that day was truly genuine. There was nothing fake about it, and somehow in my heart I felt he was listening.”

“It was,” said René Hall, the consummate a&r man, “the greatest gospel rendition I ever heard in my entire life.” According to

Ebony,

“women fainted, tears rolled down men’s cheeks and onlookers shouted,” and the renditions of two more of Sam’s gospel favorites by Bobby “Blue” Bland and Arthur Lee Simpkins, a forty-nine-year-old classically trained baritone whom Sam had known from his early days in Chicago, only added to the “genuineness,” and genuine hysteria, of the moment.

After a lengthy sermon by Reverend Charles (“Sam Cooke has lived his life. He has made his contribution. If he had not died when he did, Sam Cooke would still have to die sometime”), the funeral ended as the skies grew even darker and the thousands of people lining both sides of West Adams Boulevard held up the two-hundred-car procession for a full forty minutes before it could get under way to Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, where Vincent, too, was buried. At the cemetery Barbara picked a rose from the casket, and four-year-old Tracey said loud enough for everyone to hear, “Oh, you’re going to wake my daddy up,” as they lowered the casket into the ground. “No,” said Linda, clasping her little sister’s hand and looking very hurt and very adult, “he’s not going to wake up anymore.” It was night, and the rain was still falling.

Afterward they all went back to the house, and Barbara met with Sam’s musicians and explained that, while Sam had made no provision for them, she was going to give each a few hundred dollars, which she hoped would help, because there wasn’t going to be any more. There was some grumbling, and some remonstrance about withholding taxes that hadn’t been paid, but eventually, said June Gardner, “we split, and that was it. It was a beautiful operation, but the patient died.”

It was the end of their world. For each of them it marked a bitter conclusion, but for no one more than Barbara. She was terrified of the future, and Sam had already begun to disappear. For all his faults, he had always taken care of her. Who was going to look out for her now?

W

ITHIN JUST A FEW DAYS

of the funeral Barbara and Bobby Womack were in a full-blown relationship. As Barbara described it to her friend Gertrude Gipson for a headline story in the

Los Angeles Sentinel

one month later, “Bobby has been my constant escort for the last few weeks and has been seen with me at most of the functions I have recently attended.” Despite rumors to the contrary, she was not yet married, she said, but she showed off “a very large and beautiful ‘carat’ on her left finger . . . a gift from the musician-vocalist,” who, in an accompanying article, was described as bearing “a remarkable resemblance to the late Cooke as well as comparable mannerisms.”

Bobby’s first act even before entering into his new role was to throw Barbara’s boyfriend out of the house after the funeral. He had come by to pay his respects and found the man, the bartender from the Flying Fox, wearing Sam’s watch, ring, and robe. “I was like, ‘This motherfucker’s trying to fuck over my hero.’ I told him to take off the watch. I said, ‘Get the fuck out of here, and give me that robe, too, while you going.’ He was a big guy. He could have floored me, and I would have never known what hit me. But at that point it didn’t matter—it was the first time I really felt like a man. Barbara said, ‘I like a man who speaks up. I’m impressed.’ That was the quick move.”

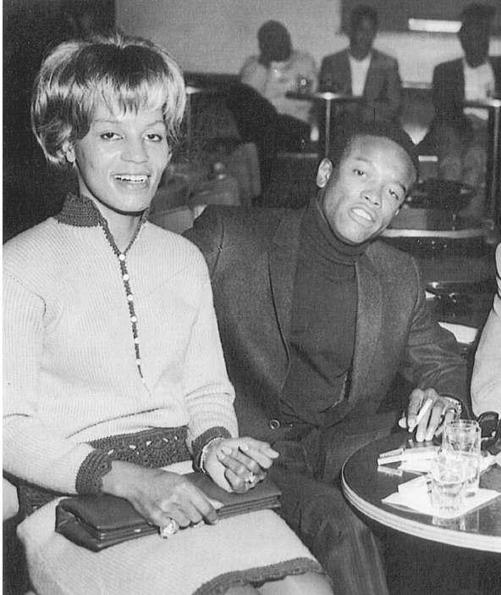

Barbara and Bobby.

Courtesy of Barbara Cooke and ABKCO

The next move was not immediately apparent to Bobby, but he could tell she was impressed enough to encourage him to keep coming around. From Barbara’s point of view Bobby’s company was not only welcome, it was necessary. She felt abandoned. Nobody cared about

her

—nobody really approved of her. And even though René and Sugar Hall and Alex and Carol still came by all the time, she could tell they were looking at her funny, they were trying to watch out in case she went off or something. Sam had made a laughingstock of her in front of the whole damn world. She took the children out of school—she didn’t know when she would send them back—she just didn’t want them to have to suffer the kind of ridicule that she sensed all around her. If her husband was going to get himself killed, why did he have to get killed in some fleabag ghetto motel? Why couldn’t he have gone someplace with someone with a little more class? At least then he wouldn’t have left her looking so ridiculous in everyone’s eyes.

Then one night, right around Christmas, after René and Sugar Hall had left and the kids were asleep, Bobby started talking about how his brothers had decided to go back to Cleveland, but he wanted to stay out here. She explained to him that she couldn’t do anything for him, she didn’t know how she was going to get by herself, but he said that he knew he had some songwriter’s royalties coming from Kags, she could just keep the money if she would let him stay and work with her. She reminded him that he was in a group with his bothers, but he said, “I don’t have to be with my brothers.” She gave him a long, assessing look, and then it hit her all of a sudden, how death and sexual attraction went hand in hand. He looked a little scared, but when she indicated her feelings, he didn’t turn her down, and that was the beginning.

Bobby remembered it a little differently. In his recollection: “She called and said, ‘Bob, I want you to come over here. Sam left something on a tape. It’s some songs, and I don’t want [anybody else] to hear what it is, and I don’t know how to work the tape recorder . . . ’ So—I’ll never forget. It was in the early evening, and René and his wife was there—I wanted to get out there early, because I’ve always been scared of dead people, like they’ll come back. Anyway, I’m trying to work the tape recorder [in Sam’s little workshop/studio], and she’s standing so close behind me I couldn’t even move my arms, and I said, ‘Damn, all you got to do is push right here, it’s easy.’ She said, ‘You never look at me when I’m talking. You afraid of women, but you ain’t that little boy no more. You got your chance now [to] be a big man.’ I said, ‘I just want to get this tape to work.’

“It was like

The Graduate.

She went back in the house and comes back in a red robe, full-length. She said, ‘You seem like you’re nervous to me.’ I said, ‘I’m not nervous. I think I might see Sam.’ She said, ‘Sam?’ She said, ‘Sam is dead.’ I said, ‘Yeah, but his spirit is all over the house.’

“Then she started saying, ‘René, when are y’all gonna be leaving? ’Cause I’m tired.’ Or something like that. So they was laughing and joking, like they knew what was happening, and I was really petrified. ’Cause I’m saying, This woman is hurt, and she’s coming on to me to get revenge or whatever, but I’m caught up in the shit. At the same time, to be honest with you, I was thinking of all the times I wanted a woman and could never get one on the road, and I got the real one now. ’Cause you could not get no heavier than this. Let me show her what I know.

“So she was telling me, like, ‘You afraid, you’re scared.’ I said, ‘I’m not scared. You know how I feel about Sam.’ So she said, ‘Well —’ And one thing led to another, and she said, ‘Give me a kiss. I mean, a real kiss.’ And she was more challenging. I didn’t like it, because she was more dominant than I ever could have been. I felt like a kid again. She tells me to go in the bedroom. I said, ‘No way. If I die, I want to die on the couch.’ She finally talked me into coming in there, and the only reason I went in was because she said, ‘I’m gonna cut out the light, and I hope you’ll be comfortable in here.’ But, you know, something weird happened, man. The next morning I woke up, and them front doors were wide open, big hardwood doors that were never open because [everybody] always went in the back—I thought he had came and opened the doors just to let me know he was there.

“I don’t remember if it was that day, but it wasn’t too long before she said, ‘Bobby, people are going to be talking about us. Why don’t you marry me?’”

P

EOPLE WERE TALKING

, and Bobby was causing trouble for at least a few of them in his efforts to take care of her. J.W. came by his place on Budlong before he had any idea that there was something going on between Bobby and Barbara. He told Bobby that the company still had money in the bank and that he wanted to invest it in Bobby and his brothers because, like Sam, he had faith in their talent and would do anything he could to keep them on the label. Instead of being flattered, Bobby went straight to Barbara, just as he had a week or two earlier about the new musical instruments Sam had bought for the band. After taking in the fact that Alexander was throwing money around that by all rights was at least half hers (and was attributable, she felt, almost entirely to Sam’s creative contributions), she asked Bobby why he was telling her this. “Sam would have wanted me to,” Bobby told her. “I just want to protect you from everybody, ’cause everybody is out to get you.” After that, he said, “she totally trusted me.”

Not surprisingly, Bobby’s protectiveness was not taken in quite the same spirit by anyone else. For J.W., there was first disappointment, then disgust. For Sam’s peers, who saw Bobby driving around in Sam’s car, dressed in Sam’s clothes and squiring Sam’s wife, it was almost like the punchline of a dirty joke. Even Bobby’s own brothers sought to distance themselves from him initially. “They said, ‘The disc jockeys ain’t gonna play our record ’cause you on it.’” The rumor was all over town that Bobby had been in bed with Sam’s old lady when Sam got killed. “I was accused of all kinds of shit, and I was totally innocent. Everybody said, ‘That little guy that he always would take [out with him], that he loved, has finally got his dream come true.’ But I can understand them taking the attitude that they did. I [should] have done it differently.”

The public outcry over Sam’s death, meanwhile, continued unabated. Talk of conspiracy abounded, with newspaper headlines suggesting cover-up and conspiracy, speculation reported as fact, and otherwise straightforward accounts heavily interlaced with irony and disbelief. “The story goes that Sam Cooke picked Miss Boyer up in a Sunset Strip bar. The story goes . . . ” was the way one ANP dispatch put it before acknowledging that “seldom in show business annals has there been so much unhypocritical postmortem expression of shock and regret.” But amidst all the hand-wringing, there were stirrings that indicated that even Sam’s adoring public might have to come to grips with an uncomfortable truth. The most commonly quoted reservation was one that first appeared in a syndicated series by A. S. “Doc” Young, “The Mysterious Death of Sam Cooke.” “Sam was a swinging guy,” an unidentified female friend of the family was quoted as saying, “but he couldn’t keep away from those $15 tramps.” Or as Bumps Blackwell put it more acerbically some years later, “I often said Sam would walk past a good girl to get to a whore.”

The precise scenario of his death remained a matter of debate among Sam’s friends and associates, but almost all could imagine how it

might

have happened, given Sam’s temper and the sense of unbridled rage that could manifest itself when he felt that he had been wronged. “He’d come out charging,” said one old friend. “He would

not

back down,” said another. There was dark talk of the Mafia; René Hall developed an elaborate theory of a drug deal involving someone closely connected to Sam in which Sam tried to intervene. Those who were less close to him interpreted the death as everything from simple betrayal to outright murder, whether by those within his domestic circle or powerful forces outside his control (“He was just getting too big for his britches for a sun-tanned man,” said one woman friend). Sam’s sisters saw it not only as altogether implausible, totally uncharacteristic of Sam’s way of life, but as irrefutable evidence of the same kind of spitefulness, envy, and racism that permeated society. Even Elvis Presley subscribed to a variant of this point of view. “You can only go so far,” he told his spiritual advisor and hairdresser, Larry Geller. “Sam got out of line, and he was taken care of.” But J.W. Alexander, Sam’s partner and friend, came to see it as little more than a tragic accident, a senseless waste of a life, while Sam’s brother L.C. announced that he was “preparing to step into the giant-sized entertainment shoes of his slain brother” just one week after the funeral, when he went into rehearsals for a memorial album and what would turn out to be a month-long memorial tour.