Dream boogie: the triumph of Sam Cooke (104 page)

Read Dream boogie: the triumph of Sam Cooke Online

Authors: Peter Guralnick

Tags: #African American sound recording executives and producers, #Soul musicians - United States, #Soul & R 'n B, #Composers & Musicians, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #BIO004000, #United States, #Music, #Soul musicians, #Cooke; Sam, #Biography & Autobiography, #Genres & Styles, #Cultural Heritage, #Biography

On Sunday, December 6, he attended the

Ebony

magazine Fashion Fair, and Cassius Clay’s photographer friend, Howard Bingham, snapped a picture of him holding hands and chatting animatedly with Miss Omega Sims. The next night, there was a Johnnie Taylor SAR session at the RCA studio, but he didn’t bother to attend. Johnnie had gotten even more of an attitude since his namesake (and he would argue his rank imitator), Little Johnny Taylor, had enjoyed a smash hit with “Part Time Love” the year before. At first Johnnie wanted to call out the other guy, whose real name was Johnny Young (“I was the Johnnie Taylor that everybody knew”), but then he began getting gigs on the basis of the name confusion, and he adapted his own repertoire to the kind of Bobby “Blue” Bland-style blues that Little Johnny Taylor specialized in. After a while a large part of the public started believing that it was

his

hit, but that didn’t stop him from running off his mouth about how Sam was holding him back. “Sam always trying to tell me how to sing a song? I know how to goddamn sing a song. That’s one thing I know how to do.” So Alex suggested to Sam that he might be better off leaving the session alone. Sam just laughed and said, “That crazy fucker. Don’t he understand we don’t give a shit as long as we go to the bank?” And he timed his arrival at the studio to when they would be finishing up so he and Alex could take Johnnie out to the California Club, where Little Johnny Taylor was headlining and they could all listen to the blues and get drunk.

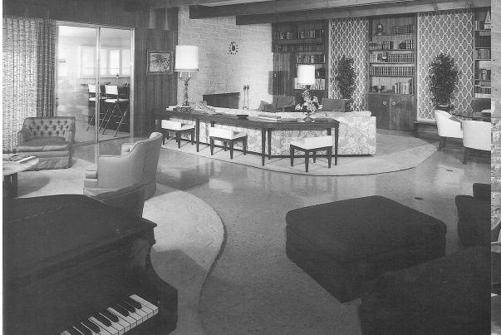

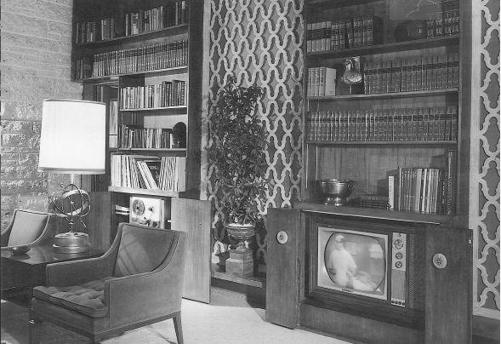

2048 Ames.

Courtesy of Barbara Cooke and ABKCO

He didn’t come into the office for the next couple of days. He told J.W. he had a cold, but Alex thought he probably just wanted to be by himself. Bobby came by the house the day before he and his brothers were planning to set out on tour, and Sam was still in bed in his silk pajamas and green terry-cloth robe in the middle of the afternoon. He told Bobby to go get his briefcase from the Ferrari and peeled off $500 from a wad of bills that Bobby thought might have added up to $10,000. He asked Bobby if that would be enough to carry them for a while, he didn’t want them getting stranded, but Bobby said that was fine, only how come he had so much money just laying around in the car? Sam passed it off with a dismissive wave. It was money he had gotten from the Peacock and the Henry Wynn tour—he had been meaning to get to the bank, he just hadn’t gotten around to it yet. Bobby nodded. Sam told him to take care of the cars and call when they got there, and Bobby said that he would.

On Thursday Sam had a dentist appointment, and he planned to stop off and see Jess Rand to wish him a belated happy birthday along with a happy tenth anniversary the following day. He called Alex and told him he would meet him at the California Club around ten o’clock that night, first he had to get together with René about some arrangements for the Deauville, and then he was scheduled to have dinner with Al Schmitt to discuss his plans for an upcoming blues album.

Lou Rawls saw Sam’s Ferrari parked outside their dentist,

Sentinel

columnist Gertrude Gipson’s brother-in-law Dr. D. Overstreet Gray’s office, and he left a note on the windshield to come by the house afterward. Sam invited Lou to join Alex and him at the California Club, but Lou didn’t think he’d be able to make it because the baby had been sick. Sam went in to see how his godson was doing, but the baby started crying as soon as he walked into the room, and they left him to his mother’s care. Sam talked to Lou a little about the kind of blues album he was planning to cut, something like Lou’s recent hit, “Tobacco Road,” but more downhome—Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker, nothing like he had ever done before. He told Lou to keep an eye out for good gutbucket material and invited him once again to come down to the club, but Lou didn’t think he could make it unless the baby was feeling better.

Barbara grew increasingly irritated with her husband as he ran in and out of the house all day. She had plans of her own, and she just wanted him out of her hair. He got a call from Crume as he was about to go out for the evening. The custom-made Dodge motor home that Sam had helped the Soul Stirrers purchase the previous year had caught fire outside Atlanta, and the fire department had had to chop it up. Sam told Crume to stay put, he would wire money to the group at the Forrest Arms early the next morning so they could go on with their tour.

Barbara got on the phone with her sister Beverly as if she were planning to spend the evening with her. Sam knew damn well that wasn’t what she had in mind and asked if she couldn’t just stay home with the kids for once. She asked if

he

was going to stay home, and then they really got into it. They had reached a standoff when she said, “You just want me to sit here until you decide to go out, don’t you?” To which he icily responded she could go out now if she wanted. But she knew he was furious because she had seized the initiative. He was supposed to be the one in control, he was supposed to be the one to bring up the subject first—it was ridiculous, but that’s the way it always was.

“I’ll probably be back early,” she said as a small gesture of apology. It made no difference, he said, he wouldn’t be there. As she was getting dressed, he came into the room and announced that he was leaving. At first he wouldn’t even kiss her good-bye. But when she reminded him, he said, “Oh yeah, okay,” and gave her a perfunctory smack on the lips.

He stopped by René’s office, and they went over the arrangements, with Sam indicating how he wanted to change some of the instrumental voicings by humming the parts into René’s tape recorder, then enunciating specific verbal instructions for each song in the show. Sam asked René if he felt like coming out to dinner, but René said he wanted to write out some of the changes first, maybe he would meet up with Sam and Alex at the California Club later.

Al Schmitt and his wife, Joan Dew, were waiting for him at the bar when he arrived at Martoni’s, on Cahuenga just above Sunset. Martoni’s had been his hangout ever since he met Jess, when Jess and Sammy had introduced him to the joint where Sinatra and all the top showbiz people hung out. It had represented a real step up the ladder when he first set foot inside the restaurant in his brand-new Sy Devore suit, nobody knowing him, trying to act like the coolest cat in the world, but now he could barely make his way to his table in the back dining room with all the people who clamored for his attention. Joan Dew thought he seemed a little distracted, but he spoke excitedly about coming off the road and how good the recent trip to Atlanta had been. He talked about the new album. This was the first Al had heard any specifics, and Sam talked about some of the musicians he wanted to use, blues musicians, but blues musicians who could play sophisticated, too. He invited Al and Joan to come out to the house over the weekend to go over material—he would barbecue some steaks, they could even stay over. Joan shuddered a little at the prospect. She was crazy about Sam, but she was the one who always got stuck with Barbara. She could never really find anything to say to her, and Barbara didn’t seem much interested anyway, but if that was what Sam wanted, she would make the best of it, for Al’s sake and for Sam’s.

People kept stopping by the table, interrupting their conversation, and after a while, Sam, who had had three or four martinis already, drifted back to the bar. Al went to get him when their orders arrived but, on returning to the table, reported to Joan that Sam was surrounded by a coterie of friends and was having such a good time that he said not to wait for him, just go ahead with their meal.

The party at the bar included a broad assortment of music industry figures, from songwriter Don Robertson to Liberty promo man Jim Benci and Gil Bogus, who did promotion work for one of SAR’s principal distributors. Sam was still ordering martinis, and after a while, at his instigation, the whole group started singing a selection of old favorites, including Sam’s “Ain’t That Good News” and the folk perennial “Cottonfields.” There was a Eurasian-looking girl, twenty-one or twenty-two with a plump, pretty face, sitting with three men in a booth by the bar. Sam nodded to her—he had seen her around—and then one of the men, a guitar player he knew from the clubs, introduced her. Her name was Elisa Boyer, and she was staying at a motel over at Hollywood and LaBrea—she had been working as a receptionist, she said, but Sam knew she was a party girl, and it wasn’t long before they cozied up together in the booth. Al and Joan stopped by on their way out to see if Sam might want to join them at the African Queen, where Al was going to check out a new RCA act. From there they were planning to go on to PJ’s on Santa Monica. Sam said he’d probably catch up with them at PJ’s as his hand rested lightly on the girl’s shoulder.

Not entirely to their surprise, he hadn’t shown up when they left PJ’s around 1:30

A.M.

He hadn’t shown up at the California Club, either, where J.W. finally gave up, bought his little girl a Christmas tree from a guy with a raggedy stand outside the club, and went home. Sam did finally arrive at PJ’s just around closing time, and he ran into a couple of old friends—but he got pissed off when a guy started talking to Elisa, and it was all she could do to get him out the door before he got into a fight.

T

HEY DROVE OUT SANTA MONICA

, then turned onto the Harbor Freeway. Now that the evening’s conclusion had been firmly established, Sam knew exactly where he wanted to go. He loosened his tie and stroked the girl’s hair distractedly, murmuring how crazy he was about her, how much he loved her pretty, long hair. In the backseat lay a bottle of Scotch and a copy of the Muslim newspaper,

Muhammad Speaks.

He was high, and he was probably driving too fast, but there wasn’t much traffic on the road and the wind felt good against his face.

The girl pestered him as they got farther and farther out of town. She didn’t see why they couldn’t go to some nice place in Hollywood instead of some out-of-the-way fleabag motel—where

were

they going? she kept asking him in between increasingly insistent pleas to slow down.

But Sam knew exactly where he was going—its remote location was part of its appeal. There were no gawkers, no celebrity stalkers, it was part of a strip of clubs and motels and liquor stores out by the airport, near where the Sims Twins lived and just down the street from the club they played all the time. It was cheap, it was convenient, but, more important, if you were a musician and liked to party, no one ever bothered you—that was the reason the Upsetters and lots of other entertainers stayed here whenever they were in town.

He turned off the freeway at the airport exit, got on Figueroa, drove a few blocks, and pulled into the parking lot of the motel, the Hacienda, with signs that announced, “Everyone Welcome, Free Radio TV, Refrigerators and Refrigeration Coming Open 24 Hours $3 up.” It was 2:30 in the morning when he walked up to the glass partition at the left of the manager’s office-apartment to register, leaving the girl in the car. The manager, a dark-skinned woman with a glowering, impassive look, just stared at him, giving no indication that she either recognized him or cared who he was. He looked like every other fool who arrived with his shirttails hanging out and a pleasantly dazed expression on his face. She saw the girl, too, and told him phlegmatically that they would have to register as Mr. and Mrs. Then she gave him the room key, and he drove around to the back, and he and the girl went into the room.

He tore off her sweater and dress, leaving her in her bra and panties and slip. He was acting a little rough, and she did her best to slow him down, but he was intent on something, and it seemed clear he wasn’t going to be slowed by either entreaty or design. She went into the bathroom and tried the lock on the door, but the latch was broken and the window painted shut. By the time she came out, he was already undressed, and he groped for her, then went into the bathroom himself, saying he wouldn’t be a minute. When he came out, the girl and his clothes were gone.