Dream boogie: the triumph of Sam Cooke (103 page)

Read Dream boogie: the triumph of Sam Cooke Online

Authors: Peter Guralnick

Tags: #African American sound recording executives and producers, #Soul musicians - United States, #Soul & R 'n B, #Composers & Musicians, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #BIO004000, #United States, #Music, #Soul musicians, #Cooke; Sam, #Biography & Autobiography, #Genres & Styles, #Cultural Heritage, #Biography

It’s hard to know what to make of this picture. It is a moment that almost defies analysis (were they doing this solely at the behest of George Klein? was it in its own way some sly commentary on the events in St. Louis just two nights earlier or, as Bobby Womack took it, the idea that “white folks think we all look alike”?). Whatever may have prompted their shadow show, it was in its own way a personification of the easygoing camaraderie and spirit of friendly rivalry that permeated the entire tour. It stands as the one permanently preserved moment of the good times that everyone enjoyed in the midst of a climate of inescapable ambiguity.

Alex left the tour the next day, encouraged by the thought that Lyndon Johnson’s landslide victory over Barry Goldwater ensured some hope of progress in the struggle for civil rights, at least for a little while. He wanted to see his baby, just one month old now, and return to business matters he had been neglecting ever since Allen Klein’s full-scale entrance into the picture fifteen months ago. With Tracey firmly established, it was time, as he saw it, to get the Los Angeles office back in order, hire a replacement for Zelda, set up some new SAR sessions, and let the distributors and DJs know that he and Sam were still in business.

Sam was no less set on his new course. The perils of the road had never been more clear-cut. Just days before, Ray Charles had been busted for heroin possession in Boston and Frankie Lymon jailed in New York on “dope charges.” Little Willie John had gotten into a barroom fight in Seattle while they were playing Knoxville, and then he had gone and killed the fucker. Sam had Crain wire him money, but he was up on a second-degree murder charge and there was no telling what the outcome might be. There was no insulating yourself from the dangers. It didn’t matter who you were or what you did, you were just a moving target. If you stayed out there, you were never going to be anything but a nigger, a nigger with money perhaps, a nigger with a fancy car or even, in Ray’s case, your own plane, but a nigger nonetheless.

He had already told L.C. and Charles what he had made up his mind to do. Clif was the only one he was going to keep, but he wasn’t going to leave anyone stranded. He was going to turn L.C. over to Montague, his brother’s original producer, and if Montague couldn’t get a hit on L.C., he just might buy the two of them a radio station. After all, they both loved to talk, and Montague had convinced Sam that station ownership was the logical extension of the communications empire he had already begun to build. Charles he was going to set up with a carwash and some real estate in Atlanta. It was time for Charles to settle down, he told his older brother, stay home with his wife and children, and Atlanta represented the future for black people in this country. He was going to send Bobby back to his brothers, he and Alex were putting their money on the Valentinos. He was going to buy his drummer and bass player new instruments, use them on sessions and the occasional live date, maybe even help June relocate to Los Angeles if he wanted to—but, unlike Clif, they would no longer be on a weekly draw. As far as Crain was concerned, he and Alex would find something for him to do. Crain remained obdurate about accepting any actual “job,” but Sam wasn’t going to walk away from the man who had first showed faith in him.

Barbara alone remained the problem. For the first time, he spoke to a lawyer about getting a divorce, but he couldn’t really imagine going through with it. He was not going to write his will, because, he told Bobby, “When a woman start asking about a will, she will kill your ass.” When Bobby remonstrated that this wasn’t anything to joke about, “Sam would say, ‘If I should die before I wake, bury me deep, put two bitches on each side of me.’ And he would laugh.” Bobby didn’t like it when he talked like that. It was as if he had misplaced the happy-go-lucky quality that had always kept him from seeming sorry or slick. His one piece of advice for Bobby when he was in that kind of mood was: Never fuck with your fans. “He was pretty cold about it. He said, ‘Every girl you go with [gets herself] a baby. Now you get you a high hooker. She knows exactly what you want, and how you want it, and all that. You can give her five hundred bucks, and she gone.’ I said, ‘Five hundred!’ He said, ‘I’m telling you, man, it save you a lot of grief.’”

B

ARBARA WAS OUT

almost every night with her bartender friend when he got home. If Sam ever came into a place she and her boyfriend might have been, he would purposefully ignore any evidence of her visit, to the point of angrily disputing anyone who might have the temerity to suggest they had seen her with the cat. “That ain’t my wife, man,” he said. “My wife don’t do things like that.” And he made it clear they had better back off—or be prepared to fight about it.

He scheduled a session with Al Schmitt to record “To Each His Own,” one of his favorite Ink Spots ballads, along with a couple of dance originals like “Yeah Man,” which had gotten a good response every time he threw it into the show on tour. The two numbers he worked up were “It’s Got the Whole World Shaking,” which he and Alex had cut on the Sims Twins earlier in the year, and a new song called “Shake,” inspired by Bobby Freeman’s big summer hit, “C’mon and Swim.” Sam had worn that record out, playing it again and again and pointing out to Bobby the groove that its producer, a young San Francisco DJ named Sly Stone, had laid down. “Man, I got to sing that song,” he kept saying, but instead he wrote his own version, which directly recalled the original only in the little slide that Bobby threw in at the end. What they wanted to achieve, J.W. said, was straightahead energy, and that was what the song communicated, from Earl Palmer’s opening drum roll to the melodic hook that René played on electric bass to Earl’s dancing riff on toms, which functioned effectively as the lead instrumental voice for the song. “We thought we had started a whole new thing,” said RCA a&r man Al Schmitt.

It was, certainly, a whole new thing for Sam, as unapologetic a pure rhythm number as he had ever cut, unmodulated by the kind of melodic touches that had accompanied even “Yeah Man” or “It’s Got the Whole World Shakin’.” It was the definition of what Sam kept telling everyone who would listen was the coming trend in popular music and r&b, something that, like James Brown’s raw extemporizations, the Valentinos’ and the Rolling Stones’ rough-edged rock ’n’ roll, was conveyed as much by rhythm and attitude as it was by vocal technique. It used to be, he explained, that sound brought attention to the lyric, but what you needed to do now was to find sounds—as opposed to words—that could emotionally move an audience. And that was precisely what he had achieved here.

With the session at an end, he and Alex turned their attention briefly to preparing “A Change Is Gonna Come” for single release. After ten months of listening to Allen sing its praises, Sam had finally agreed to revisit the song that had caused him so much inner turmoil and put it out as the B-side of “Shake.” Now he and Alex set out to edit the song for radio airplay, in consultation with Al Schmitt. They needed to cut at least thirty seconds from its album length, and Sam was adamant that he didn’t want to lose either the cascading overture or the coda at the end. What this pointed to was deleting the verse and chorus just before the bridge, which included one of Sam’s most direct statements of social criticism (“I go to the movies / And I go downtown / Somebody keep telling me / Don’t hang around”), but it permitted him to retain the bitter realization at the heart of the song (“I go to my brother / And I say, ‘Brother, help me, please’ / But he winds up knocking me / Back down on my knees”), along with the final verse and chorus, which served, however tentatively, as its underlying statement of redemption and belief.

With everyone in agreement on what had to be done, they left the actual editing to Al Schmitt and went off to the Gaiety Deli on Sunset with Clif, René, and Earl Palmer. Sam and Earl reminisced about Sam’s first pop session in New Orleans, in 1956, just before Earl himself moved to L.A., joining Clif and René on the studio scene. It seemed like a lifetime ago to them all, and they talked about Jesse Belvin and the career he might have had if he hadn’t been cut down by those racist motherfuckers in Arkansas. Earl asked Sam and J.W. about the Copa, and they told him how great it had been. “A little nigger in the Copa!” said Sam with almost childlike delight. “A little nigger was in the Copa!” They talked about Mel Carter and his new deal with Imperial and how much they all missed the opportunity to watch Zelda tan. Some white girls came by to get Sam’s autograph and practically fell all over one another as he signed their little pieces of paper, but he didn’t pick up on it and just sent them on their way. It was well after midnight, the end to a nice relaxed evening in which much had been accomplished, and after they finished their drinks and sandwiches, J.W. got his cheesecake, and they all headed off in various directions of their own.

Sam had one more week at home before returning to Atlanta to play the Royal Peacock for Henry Wynn over the Thanksgiving weekend. It was

The Sam Cooke Show,

with the Valentinos and the Upsetters on the bill, a nice way to pick up some change and repay Henry a little for all of his kindnesses over the years. Four weeks later, he would be opening at the Deauville, then the Fairmont in San Francisco, and then—who could say for sure? The movies definitely, maybe even producing movies of his own. The Palladium in London. A one-man show at Carnegie Hall, delineating the development of Afro-American music in this country. Las Vegas. He doubted that he would be passing this way again.

Oh, they tell me of a home far beyond the skies

They tell me of a home far away

They tell me of a home where no storm clouds rise

Oh, they tell me of an uncloudy day

T

HE WHOLE FAMILY

flew into Atlanta the Tuesday before Thanksgiving for Sam’s five-day engagement at the Royal Peacock. Sam, Barbara, and Tracey occupied a corner suite at the Holiday Inn, while Linda stayed with the Wynns, whose daughters, Claudia and Henrietta, took her to school with them. The last time Sam had come through town with Alex, they had run into Martin Luther King at the airport, pausing for a moment under the terminal’s harsh fluorescent lighting to exchange greetings. Martin asked if Sam would perform at an SCLC benefit early in the new year, and Sam instantly agreed, and then they all hurried off to catch their respective flights.

This time Sam was determined to just make the most out of what amounted to an extended breakup party for the band. Every night the club was packed, and Barbara, who rarely came to the shows when she had the kids with her, was in regular attendance with Sam’s friends, the Paschals, a wealthy black family with a restaurant, a hotel, and an upscale jazz club, who provided her with a babysitter for Tracey. Lotsa Poppa, whose new single paid explicit tribute to Sam with a gospel-laced medley of “That’s Where It’s At” and the Falcons’ “I Found a Love,” managed to catch the show, too, even though he had a gig of his own at the Magnolia. He came by on Saturday night in a powder-blue leather suit, and Sam had everyone turning their heads to look as he laughingly declared from the stage, “Boy, that’s the first time I ever seen a big man with a leather suit that color.” Seventy-four-year-old Carrie Cunningham, who had opened the Royal Peacock fifteen years earlier after coming to town in the thirties as a circus rider with the Silas Green tent show, was sitting at a front-row table. She was a tall, regal woman who had known everyone on the entertainment scene over the last thirty years, and Sam was in the middle of a laid-back, mellow kind of set when he leaned over and dedicated his next song to Miss Cunningham and Mr. and Mrs. Jefferson, the owners of the Forrest Arms Hotel. The song was “A Change Is Gonna Come,” and Lotsa would always remember it because of the way it just tore the place up.

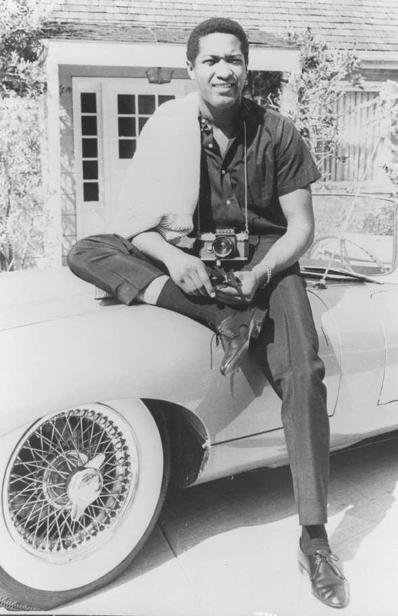

With camera and XKE, 2048 Ames.

Courtesy of Joe McEwen

On the last night of the engagement, Sam threw a dinner for the band and hit everybody with some money. He told them all to get Christmas presents for their wives and children and gave June his ticket to Miami, where they would be meeting up in three weeks for the Deauville date.

He had no special plans for his time at home. Mostly he looked forward to being able to just kick back and relax—listen to his music, drink his Scotch, not even answer the phone. Bobby came by early in the week, and Sam once again ran down all the reasons for sending him back on the road with his brothers. He knew Bobby’s feelings were hurt, but it would be better all around. Bobby’s brothers needed him, and now that they would be headlining their own tour with L.C. and the Upsetters, Bobby would see—it might be hard at first, but he would see—how much better it was. Sam was giving them the Checker and his old limo for the tour. “It’ll keep me from having to send L.C. money,” he joked. “Man, it’s better for you all to work.” When he sensed that Bobby might not be altogether convinced, he said, “You know, I’d be selfish if I kept you as a guitar player just so you could play for me. I have to realize that, as a businessman, I have to turn certain things loose from my own fancy.”